Last week I sat in a lit, crowded multiplex theater near Times Square, awaiting a preview screening of The Equalizer, director Antoine Fuqua’s big-screen adaptation of the ’80s TV series. A few minutes before the movie began, a couple of twentysomethings next to me got into a discussion about what they were about to see. “So is this, like, a highly rated movie?” one asked. “I dunno,” his friend replied, then added: “It’s a new Denzel movie.”

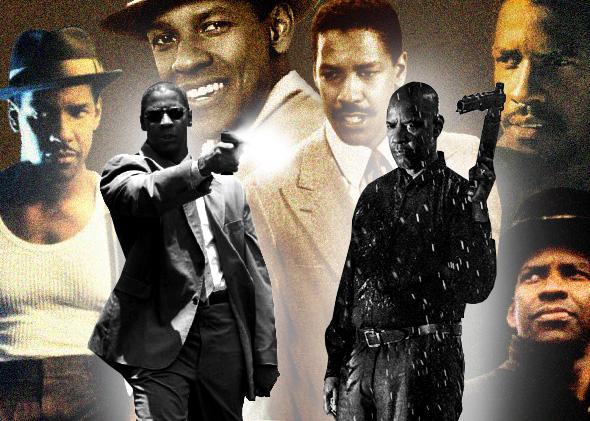

What exactly is a “Denzel movie”? In 2014, it means the Hollywood star, now nearly 60, being a badass. Lots of gun-wielding, fistfights, killings; some scenes of torture; maybe an explosion here and there. The stakes are improbably high, and the star navigates them sporting his familiar, undeniably cool demeanor and trademark megawatt grin. You’ll find all of this in The Equalizer, in which Denzel—and of course he is “Denzel” to all of us, not “Washington”—plays a former Special Forces soldier who comes out of retirement to save a young prostitute from a predictably tattoo-adorned Russian mob.

The formula is clearly working—he’s one of the few major Hollywood players of the ’80s and ’90s who’s still a consistently bankable star. He certainly doesn’t look like he’s approaching his seventh glorious decade on Earth, and his box office clout has only grown: Out of his last 17 films, only three have made less than $50 million; most have made upward of $70 million.* Compare that to his career prior to 2000, where all but six of his films fell below $50 million.

But is this how we hope the greatest film actor of his generation spends his time? Denzel isn’t Will Smith, who has always been vocal about his desire to be the biggest movie star in the world. Denzel was that very rare contemporary Hollywood star, the kind who simultaneously graced Sexiest Man Alive lists (with lyrical shoutouts from admiring ladies) and Oscar ballots, even winning a couple in the process. Rarer still, he did it all while being black, carrying the baton handed to him by Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte, running with it gracefully. And now, in The Equalizer, he’s playing a half-baked variation of the “retired gunfighter” trope in a junky action movie. Denzel deserves better.

How did this happen? Training Day, directed by Fuqua, sowed the seeds for the badass Denzel we know of today, casting him against type as a dirty, rogue cop with virtually zero redeeming qualities. It wasn’t an action movie—really it was a gritty two-hander with indie DNA—but it resembled an action movie if you squinted at it just right. Denzel won an Oscar for Training Day; made the two modest dramas (John Q and Antwone Fisher) that both disappointed; and then went straight to a big-budget, all-action extravaganza. Man on Fire, directed by five-time Denzel collaborator Tony Scott in 2004, watered those seeds and kept them growing. He plays an ex-CIA officer, now a bodyguard, who seeks violent revenge on the kidnappers of his young charge, played by Dakota Fanning.

Since then, he’s played a lot of loners entangled in dangerous circumstances: In last year’s truly terrible action-comedy 2 Guns, Denzel plays a loner undercover DEA agent forced to team up with Mark Wahlberg to battle dirty military agents and the Mexican mob. In Safe House, he’s a former CIA agent turned fugitive on the run from rookie agent Ryan Reynolds in a dangerous chase for top-secret data. Unstoppable and The Taking of Pelham 123, both directed by the late Scott, involve rogue trains—the former a runaway containing dangerous chemicals, the latter taken hostage by an unabashedly campy John Travolta—that must be saved by everyman Denzel. In the post-apocalyptic The Book of Eli, he must save humanity.

The action movie genre, as entertaining as it can be, doesn’t play to Denzel’s strengths: vulnerability and droll humor. In all of these roles, Denzel’s range as an actor is distilled, his solemn side embraced to the point of near humorlessness. His characters are too preoccupied with trying to defuse catastrophic situations to reveal nuance—in Unstoppable, for instance, his personal issues at home (a strained relationship with his teen daughters) are clumsily inserted into the runaway train narrative via clunky heart-to-hearts with his younger co-star, Chris Pine. And while 2 Guns is supposed to be an action-comedy, the script works way too hard—there’s no room for Denzel’s easy sense of humor.

It’s not that these performances are bad, exactly. He hasn’t reached De Niro levels of awfulness just yet. He can still bring profound weight to these roles, as in Pelham 123, when Travolta’s villain wrangles Denzel’s NYC subway dispatcher into a confession of having taken a bribe over a contract, in front of all his colleagues:

Denzel embodies vulnerability and frustration in this scene, stuttering embarrassedly while Scott’s camera circles him intensely. But such moments, which could be found so often in his earlier films, are fewer and further between in his race-against-the-clock, life-or-death filmography of late. The Equalizer renders this most acutely and ridiculously—the violence is slickly choreographed and staged, with Denzel using martial arts and gun expertise to kill and fend off the Russian mob. A long, protracted climax is the adult-sized version of Home Alone, with Denzel setting up various booby traps in the home-improvement warehouse where he works to, among other things, hang and impale his adversaries. No time to be vulnerable when there’s impaling to be done.

And the movie even features the archetypal badass movie shot: Denzel, cool as ice, sauntering in slow motion toward the camera as, behind him, a shipyard is blown into fiery bits. The audience at my screening cheered when the fireball went up.

Denzel starred in action movies early in his career as well, of course. Some of them were really bad. But for every Fallen there was a He Got Game; for every Virtuosity a Philadelphia. In the 1980s and 1990s, a “Denzel movie” wasn’t so clearly defined as it is now. Sometimes his characters were aggrieved, resentful men pushed to their breaking points, like Pfc. Peterson in A Soldier’s Story and Pvt. Silas Trip in the Civil War drama Glory (that horrific, perfect single tear may have single-handedly won him his first Oscar). He often worked with exciting, challenging directors: Spike Lee brought out the best of him in Mo’ Better Blues, He Got Game, and, of course Malcolm X; Mira Nair made him a charming, complicated romantic lead in her thoughtful interracial love story Mississippi Masala; he returned to his early stage roots and tackled Shakespeare in Kenneth Branagh’s delightful Much Ado About Nothing.

One thing he never was, though, was boring. In Carl Franklin’s criminally underrated 1995 neo-noir film Devil in a Blue Dress, for instance, Denzel exquisitely embodied the weary, postwar male archetype that characterized such classics as Out of the Past and In a Lonely Place. Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins, an out-of-work World War II vet who finds himself entangled in the seedy, racist underworld of Los Angeles politics and law enforcement, is an iconic Denzel role, one that makes the most of his gift with sharp, playful dialogue. (Franklin adapted the screenplay from Walter Mosley’s novel.) He’s given moments to be utterly sexual (as when he “hits the spot”—till sunrise—of his friend’s girlfriend), vulnerable (the tense encounter when some angry whites notice one of their girlfriends chatting him up on the boardwalk), and passionate and angry (his edgy, fast-talking confrontation with a nightclub bouncer entangled in a murder).

Unlike early Robert De Niro or Al Pacino, Denzel rarely “disappears” into his roles; even when he’s taking on as larger-than-life a figure as Malcolm X, you’re always aware that you’re watching Denzel onscreen. His cadence is comfortingly familiar; that megawatt smile, often punctuating moments of intense moral seriousness, is instantly recognizable. In this way he was one of our few great actors who was also, effortlessly, a movie star.

Yet Denzel is now approaching the status of aging action hero: an elite but mildly pathetic club that includes Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis, and Arnold Schwarzenegger. (I suppose we can be grateful he didn’t appear in The Expendables 3.) What’s especially weird about this career arc is that he came to the party late—Stallone and the rest of the club began and made their careers as action heroes and never really left, so it’s unsurprising that they would try to rekindle the fire well into old age. In this career left-turn Denzel most closely resembles Liam Neeson, another dramatic, invigorating performer who’s turned to a steady diet of action (anti-)heroes later in his career. As with Neeson’s, Denzel’s ride has been fun at times, but surely this is not the only side of him fans want to see from now on. (There’s even talk of The Equalizer serving as the introduction of a franchise, which would be a first for Denzel—who, despite repeating himself many, many times over the last few years, has never made a sequel.)

There may still be hope. It was only two years ago that Denzel played Whip Whitaker, the alcoholic, coke-snorting pilot who manages to save his doomed plane in an inebriated haze. The role in Robert Zemeckis’ Flight brought out a dark, new variation on the Denzel brand, with a character arc—from reckless drug abuser to pitiful, angry recluse to wearied, repentant soul—that served as a reminder of all the great things Denzel is capable of. When Whip confronts his colleague at the funeral of one of his dead crewmembers about keeping his intoxication during the flight a secret, the desperation to cover up his own lies is painfully palpable.

The actor took a pay cut to play Whip, which earned him his first Oscar nomination since Training Day. His reason for doing so? “The script,” he told Deadline around the time of the film’s release. “As simple as that. Good scripts are hard to find.” A charitable way to view Denzel’s turn to action in the past decade is not that he’s gotten complacent or bored; even an actor of his caliber is subject to the typecasting that drives the economics of Hollywood, and if all Denzel gets is scripts that have him playing foil to Russian mobs, Mexican mobs, and everything in between, what can he do?

But I hold out hope that someone, perhaps an up-and-coming director, will give Denzel the chance to be Denzel in a new way, for the last act of his career. Imagine what Ava DuVernay, for instance, of the beautifully wistful Middle of Nowhere and the upcoming MLK biopic Selma, could bring out of him, with the right script and supporting cast. Or Ryan Coogler, whose impressive debut was Fruitvale Station? Heck, I’d even be curious to see Lee Daniels tackle Denzel—his filmmaking may be uneven, but he gets great performances out of his stars.

Denzel could even stretch his wings and try out another full-on comedy role. The current Denzel type often reads as humorless, but in fact he’s a nimble comic actor: He was absolutely charming reinterpreting Cary Grant’s guardian angel in The Preacher’s Wife, the 1996 remake of The Bishop’s Wife; in the 1989 Caribbean-set mystery The Mighty Quinn he was easygoing and mischievous; in Much Ado About Nothing he warmed up the sometimes wan role of Don Pedro. Even when he’s serious, Denzel has shown flashes of humor: In The Equalizer, he kids a younger co-worker that he used to be one of Gladys Knight’s Pips, and breaks into a little dance, grinning irresistibly. Denzel has expressed an eagerness to return to comedy—a long-rumored plan to remake Uptown Saturday Night has been all but confirmed by him, though supposed co-star Will Smith seems to be slowing things down. To that I say: Big Will, don’t screw this up.

And of course Denzel has earned the right to make action movies if that’s what he’s happy doing. Sometimes, when he’s in that rare exceptional one, like Inside Man, it’s thrilling. But he could stand to take a page from his contemporary Jeff Bridges. Only a few years older than Denzel, Bridges has invigorated his career by dabbling in indies (Crazy Heart), prestige flicks (True Grit), and paycheck roles (Iron Man). He too has crafted a persona over the years, just like Denzel, but he’s found use in varied shades of those personas in different kinds of films. Denzel should do the same—he’s more than proven to us that he can be our hero. Now it’s time to remind us of the days when he was a complicated, interesting human being—albeit a much cooler, better-looking one than most.

*Correction, Sept. 25, 2014: This article originally misstated that Denzel Washington is approaching his sixth decade on Earth. He is approaching his seventh.