In what would become the first scandalously record-breaking Sotheby’s art auction in 1973, taxi magnate Robert Scull and his wife famously made a fortune on 50 artworks from their collection, which included Robert Rauschenberg’s painting Thaw. There, the artist watched as his piece, which he had initially sold for $900, hammered out for a whopping $85,000. As the story goes, Rauschenberg famously shoved Scull and shouted something along the lines of: “I’ve been working my ass off just for you to make that profit!” (The exact quote varies, but you get the drift.) Rauschenberg didn’t see a dime from that auction; unlike authors and composers, American artists get no cut of their future sales.

This is because U.S. copyright law protects “published” works, and a work of art is not “published,” simply made and sold—so once a work of art is out of an artist’s hands, the future profits, too, are gone. This system is unique to the art world; in other fields, artists are understood to have the right to a share of the proceeds of their works long after the works are first made. It makes perfect sense, for example, that the Isley Brothers would keep making royalties off “Shout,” even though it wasn’t a chart-topper when they released it in 1959 (it didn’t become iconic until it was featured in Animal House in 1978), or that Joan Didion would keep collecting money off Slouching Towards Bethlehem, which was published when she was 34, before her legend was secure. In the music world, a minor scandal arose when Chuck Berry was cheated out of part of his royalty rights for “Maybellene.” In the art world, everybody is Chuck Berry.

As for Rauschenberg, he funneled his outrage on the warpath for artist resale royalties, and eventually paved the way for the 1977 California Resale Royalty Act—the first artist royalties provision in U.S. history. For a brief time, that law gave some American artists a taste of royalties, until it was struck down in 2012. Meanwhile, artist resale royalties (or droit de suite) have long been a basic right in 70 other countries; France has had such a system since 1920, and the European Union standardized it across the continent in 2001. They’re so common that the U.S. Copyright Office specifically revised its position on artists’ royalties last year, recommending that Congress revisit the issue.

Now, Congress has that chance: the recently proposed American Royalties Too (A.R.T.) Act, a bill which would give artists a 5 percent cut of the profits when their works are resold at auction. The bill has its flaws: It applies only to auctions and not private dealings. But 5 percent is also a slim and fair share, compared with the auction houses’ 12to 25 percent buyers’ premiums—though even 5 percent looks too fat to slip under the door. An earlier version of the bill, the Equity for Visual Artists Act, failed to attract a single co-sponsor in 2011, and over the past few years, Christie’s and Sotheby’s have been raining upward of $1 million on lobbying against royalties. At this writing, govtrack.us gives the A.R.T. Act a 2 percent prospect of being enacted.

Given the surge of multimillion-dollar auction records boasted by Christie’s and Sotheby’s on an almost monthly basis, how do the auction houses justify lobbying against a bill that might pay artists for their works? When Art F City asked a Christie’s spokeswoman, she insinuated that successful artists simply don’t need more money: “European studies have shown that resale royalty schemes provide support to less than 5% of working artists, and the artists receiving royalties tend to be those commanding the highest prices on the primary market.”

Sure, for most artists, large secondary markets are a best case scenario. But only a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry would force us to re-examine a kindergartener’s understanding of ethics. Whether artists are successful or unsuccessful, making millions or pennies, they deserve to share in the money their work generates. “The A.R.T. Act won’t benefit every artist, unfortunately, but this is not an anti-poverty program,” Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.), sponsor of the failed 2011 Equity for Visual Artists Act, told me over the phone. “This is a fairness and equity program. Just because we can’t bring in everybody doesn’t mean we should bring in nobody.”

And in the art world, even “success” can be deceptive; artists who periodically sell well at auction don’t necessarily make a cozy living. “Nobody escapes falling on hard times,” artist Marilyn Minter told me. “I think all artists have a really hard time at the beginning, middle, or end of their careers; it’s up and down like a yo-yo, and some people have it twice.” For most, even the “yo-yo” career remains aspirational. “Personally, the A.R.T. Act would not translate into any kind of immediate windfall for me,” the artist William Powhida told me. “I’ve only had one small work come up at auction, which sold for under $3,000. I am hopeful, though, that in 10–15 years that might be a different story for my work, but that is almost besides the point.”

It might be safe to say that if Robert Rauschenberg has produced an heir in today’s New York art world, it’s Powhida. In blisteringly searing cartographic drawings like “How the New Museum Committed Suicide With Banality,” Powhida methodically plots out conflicts of interest, celebrity mania, and speculator motives. Other to-do list drawings, like “Things I Think About When I Think About Bushwick,” give bitter voice to the crushingly unrealistic hopes of legions of disenfranchised artists. These days, you’ll meet him person at affordable housing meetings, panel discussions, and picket lines all over the city.

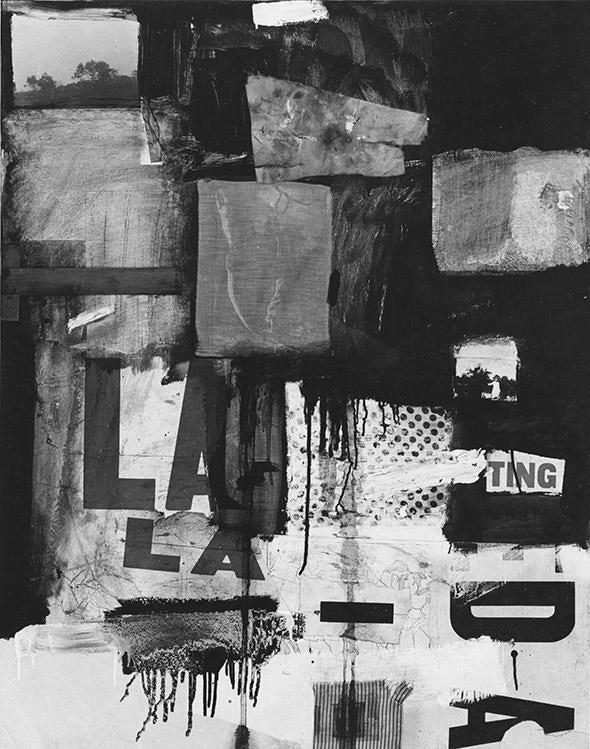

Photo by Michael Mandiberg

I have my own selfish reasons to hope that the A.R.T. Act would someday benefit him. Powhida had been a personal hero of mine long before I moved to New York; his work was taught to me in art history 101, and his unfiltered professional voice inspired me, as a meandering painting graduate, to be bold and abrasive about art world injustices. He was somebody I feared and admired, and I was probably not the only art student eager to blaze behind his trail. I didn’t fully appreciate what that would mean, though, until last winter, when I worked as his studio assistant in Bushwick.

“As something of a midcareer artist approaching 40, I have never made enough money from art sales to quit my day job as an art educator,” Powhida, who for many years taught art at a Brooklyn high school and now co-directs a residency program, reflected recently over email.* “A painter I know incredulously questioned me about my commercial success: ‘Come on, you’re the most famous artist I know, and you can’t make $40,000 a year doing this?’ While my friend was half-joking, I think his comment revealed the gap between being a commercially successful artist and having a successful art career.”

As I realized slowly after moving to New York, nothing gets easier. All my heroes are poor, and very few of my peers are saving; people are working multiple jobs outside the field to pay for a studio in the city where the connections are—and making the connections by working unpaid jobs in their studio time.

Artists and allies have proposed a number of alternative approaches to royalties, which could touch the lives of many more artists. The group Level Rights has drafted a one-time, voluntary resale royalties contract, which was recently tested out at Bushwick’s NEWD Art Show. William Powhida would like to see a percent of auction profits be split between royalties and a general museum acquisitions fund.

So far, though, these propositions haven’t got legs. Instead, the grumbling froths up regularly around auction season, as it did recently at Christie’s $134.6 million bad-boy auction “If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday.” The sale featured an untitled print by Wade Guyton, made in 2005, when he was still a rising artist and was selling similar works, according to his gallery, for around $8,000. Possibly disgusted by the $2.5 million to $3.5 million estimate, Guyton printed dozens of identical images and posted photos to his Instagram account—instantly devaluing the uniqueness of the work on sale—with foreboding hashtags like #winteriscoming, #deflationarypolicy, and #ifiliveauction. But hours later, the work hammered out, as planned, for $3.5 million anyway. Christie’s even incorporated the protest into their advertising for the auction, remarking on his stunt: “Fun.”

Of course, Christie’s can afford to laugh it off. But their sense of humor is harder to appreciate, after years of watching your friends and mentors struggle to buy a sandwich or a roll of tape. It’s telling that in more than 70 countries that have now adopted some form of artist royalties, the only major debate has come from the U.K., which has the second largest art market after the U.S., and adopted artist royalties in 2006. When droit de suite was proposed for the U.K. in 2000, the British Art Market Federation forecasted implosion: Even a 4 percent royalty could send thousands of jobs overseas, they warned, and affect five times as many sales as covered by droit de suite. The alarms managed to stall the implementation of droit de suite in the U.K. until 2006. But years after implementation, studies have shown that the law barely affected sales.

If that’s any indication, artists’ royalties don’t harm the market. They can provide some measure of security to artists, especially later in life; they are common most everywhere in the world; and they are recommended by the U.S. Copyright Office. But all this is beside the point. America forgot about a basic rights law, and for many, the conversation comes a lifetime too late.

Correction, June 30, 2014: This article incorrectly stated the current day job of artist William Powhida. He worked for many years as a high school teacher but now co-directs a residency program. (Return.)