Actress Margot Robbie looked radiant in a cream silk Gucci gown embroidered with crystal and emerald with a plunging neckline and high slit. Orlando Bloom matched a bowtie with his tux.

—The Hollywood Reporter, on the 2014 Golden Globes

Red-carpet reviewers love to offer up breathlessly detailed descriptions of starlets’ resplendent gowns, shoes, and accessories. Male attire, by contrast, is typically treated as a footnote. This bias is partly the result of the tuxedo’s intentional deference to the finery of the fairer sex. But it is also reflective of commentators’ ignorance of what defines a good tuxedo. With the granddaddy of red-carpet ceremonies just around the corner, here’s your own expert guide to separating the James Bonds from the Justin Biebers.

The first step to becoming an expert tux watcher is placing the garment in historical context. Unlike Uggs or parachute pants, tuxedos didn’t just show up in stores one day on a designer’s whim. Men’s formalwear has served a very specific role for two centuries, and a basic knowledge of its past is essential to assessing its successful execution in the present.

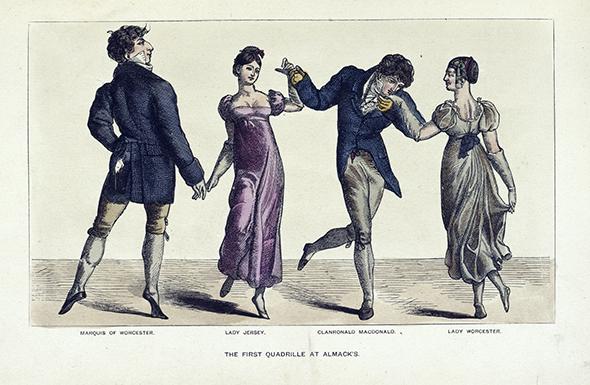

The roots of modern formalwear can be traced back to the age of Jane Austen. Prior to that time the attire of upper-class men was an ostentatious spectacle replete with brightly colored and heavily ornamented coats, lacey shirts, tight breeches, and silk stockings. Then, around the turn of the 19th century, the aristocracy made a radical shift away from this effete image of the royal courtier and toward the more masculine concept of the country gentleman. This more somber and austere aesthetic would define men’s clothing for the next 150 years.

Photo courtesy British Library

As always, the gentry reserved their finest apparel for evenings. While daytime might be spent outdoors or among mixed company, evenings were for socializing with peers at elaborate formal dinners, opera parties, and private balls. For the English Regency gentleman, the foundation of his new evening wear was a tailcoat and trousers of dark hues that harmonized with his candlelit settings and imbued him with an aura of stature and power. With this he wore a short waistcoat, soft shirt, and layered cravat. The pairing of these white linens with the dark suit created both a striking contrast and a minimal color palette, engendering a sort of sartorial chivalry by allowing the men’s formal attire to supplement the ladies’ finery instead of competing with it.

Photo courtesy PBS

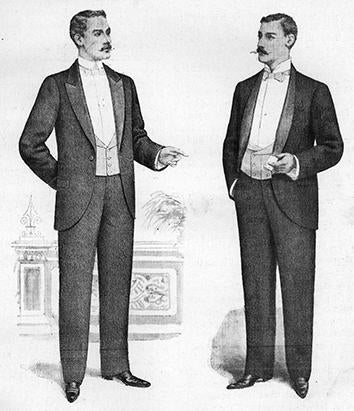

As the Regency progressed into the Victorian era this “full dress” ensemble remained de rigueur after 6 o’clock among polite society. It also became increasingly codified as the barons of the industrial revolution adopted it en masse for the air of respectability it offered the wearer. Shirts fronts and tall wing collars were starched to cardboardlike stiffness, neat bow ties replaced elaborate cravats, and the overall color palette was reduced to a strict black and white minimalism. If you’ve seen the men of Downton Abbey dressed for dinner you’ll know the look precisely.

Illustration via Wikimedia Commons

Not surprisingly, the practice of dressing like an orchestra conductor every evening eventually began to chafe on many men, and a search began for a more comfortable alternative for informal nights. The solution arrived in the 1880s in the form of the casual short suit jacket dressed up with the silk lapels and black shade of the tailcoat. Apparently in Victorian times this was considered letting your hair down. As such, its appropriateness was strictly limited to at-home dinners, private men’s clubs, and hot summer nights.

Of course, social standards have loosened somewhat since Queen Victoria ruled the British Empire. By the roaring Jazz Age of the 1920s the youthful dinner jacket had supplanted the patrician tailcoat as de facto evening attire at speakeasies and night clubs everywhere. By the 1930s it was worn exclusively with the black bow tie and black waistcoat, leaving the white versions solely for full dress and giving rise to the Black Tie and White Tie dress codes we still employ today.

Photo courtesy Dr. Macro’s

The outfit was also bequeathed a number of informal alternatives for hot-weather occasions. The white jacket absorbed less heat, the double-breasted jacket did away with the need for a waist covering, and the soft-front shirt with turndown collar wore more comfortably. The most novel option was to replace one’s waistcoat with the cooler cummerbund adapted by British military officers from the tropical sashes worn in colonial India. Topping off the swank Depression-era developments, midnight-blue became an acceptable substitute for black thanks to its tendency to appear darker and richer under electric light. This was arguably the golden age of the tuxedo, immortalized on the silver screen by icons such as Fred Astaire, Clark Gable, and Humphrey Bogart.

After World War II, social standards eased once again and the tuxedo took on a more democratic role. Instead of being mandatory evening attire for the well-to-do it was now a special-occasion kit for men of all classes, thanks in no small part to the increasing popularity of rentals and ready-to-wear clothing. In addition, the pre-war summer variations became acceptable year round. (The white jacket was the sole exception: Wearing one beyond the confines of a summer resort would still mark the owner as a waiter or hired musician.) This led to the relaxed refinement we now associate with Cary Grant, the Rat Pack, and the fictional Mad Men.

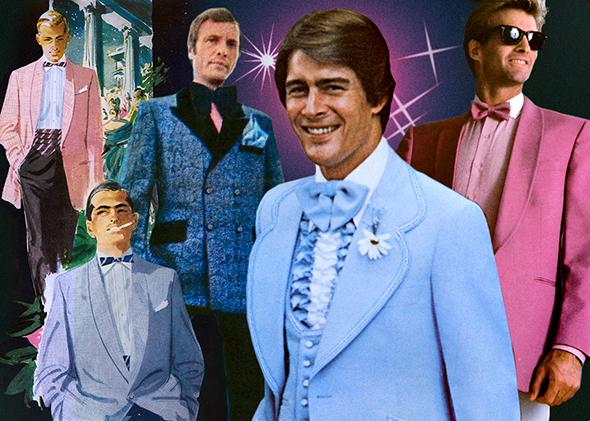

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos via author’s collection.

Then the ’60s came along and everything went to pot. (Literally.) As the first post-war generation came of age they wanted nothing to do with their parents’ traditions. Consequently, formal conventions were either rejected or blithely reinvented in their hippie image. The outcome for formalwear ranged from lapel-less Nehru jackets popularized by the Beatles to the theatrical neo-Edwardian fashions parodied in the Austin Powers movies. Later on, the disco era ushered in pastel-colored suits, extravagantly ruffled shirts, and titanic bow ties. In the 1980s Gen X-ers laughed at their own parents’ outlandish inventions only to embrace tiny wing collars and miniature colored bow ties with matching cummerbunds. The 1990s then gave us the New Wave look of “creative black tie” and the new millennium reduced the tuxedo to a black business suit and tie.

Which brings us to the present day. Using our newfound understanding of the tuxedo’s historical purpose and long evolution, we are now ready to separate today’s winning interpretations from the supporting players.

The Ultimate Ensemble

Photos by Getty Images

At the apex of the formalwear hierarchy is the outfit favored by men of distinction who understand the benefits of timeless style. It exudes the refined minimalism developed by some of the 20th century’s best dressers and often carries the Tom Ford label.

This rare ensemble is distinguished by a jacket closing with only one button so as to reveal a deep “V” of white shirt-front. The jacket’s lapels are peaked or shawl style. The first shape draws the eye upward in a sweeping motion suggesting athletically wide shoulders and a trim waist. The shawl collar is more low-key but equally debonair thanks to its exclusive association with formal apparel. These lapels are faced in satin or the more understated grosgrain texture so favored by the Brits. The same facing is also used to trim pockets, buttons, and trouser outseams. The pockets are devoid of flaps so as to minimize clutter on the coat and emphasize clean lines. For similar reasons, the jacket is devoid of vents. The suit’s wool is either black or midnight blue. Cream or ivory jackets are also acceptable provided the locale is considered at least subtropical.

Just as important as a tuxedo’s features is its fit, a fact overlooked by many novice dressers. In this regard it must meet the same standards as any other good suit: It should not be so large as to hang off the wearer’s frame nor so small as to squeeze it like a sausage casing. The sleeves and should be just short enough to display a generous portion of smart white shirt cuff and the legs just long enough to touch the top of the shoe rather than pooling at the ankle. The trousers must sit up at the waist to give the impression of long legs and a statuesque physique when the jacket is open. (This is done by means of suspenders or, for those with Daniel Craig’s abs, just the trousers’ side tabs.) The tuxedo’s cut, though, is irrelevant. Wide versus narrow lapels and baggy versus fitted styles come and go with the times but don’t affect the overall look, provided the accessories share similar proportions.

Turning to the ideal shirt, the standard turndown collar is the default style now that the regal detachable wing collars of old are virtually extinct. The front of the shirt is double-layered like the collar and French cuffs so as to ensure a snow-white appearance. This formal bosom is tastefully decorated with subtle pleats or a piqué texture and closes with equally elegant studs.

To avoid buckling, the shirt’s bosom often stops short of the waistline. The remaining portion of the shirt’s front as well as the trousers’ waistband is therefore discreetly covered by a waistcoat or a cummerbund. The former features a uniquely low cut to align with the tuxedo jacket’s opening while the latter is constructed of fabric that matches its lapel facings. Both types of waist coverings are typically black to correspond with the rest of the suit. The choice of covering is purely arbitrary as a smart dresser will keep his jacket buttoned when standing so that it blends seamlessly with the trousers to emphasize his height.

The bow tie is also black and of the same material as the suit’s facings. It can be of various shapes but is always tied by hand for a personal touch.

The shoes round out the outfit’s refined simplicity. Either pumps, loafers, or slim-soled laced shoes are fine provided that the toe of the latter is free of seams or decorations. Patent leather’s exclusivity to formalwear makes it an ideal choice but calfskin is also fine provided it is polished to a mirrorlike finish to complement the rest of the rig. Socks are ideally a luxurious silk or else a cotton lisle with a similarly swank sheen.

A white linen pocket square is a dapper but optional finishing touch.

The end result of this attention to detail is the stunning embodiment of a century of impeccable formal dressers spanning from Jane Austen’s Mr. Darcy to Cole Porter, Frank Sinatra and James Bond. Note that embodiment is the key word here, not imitation. The modern-day matinée idol is very much open to modifying the golden rules of formalwear but ensures success by honoring a couple of crucial principles. First, he understands that “formal” is defined as the preservation of form. For this reason any transgression of conventional rules should be minimized in its quantity and visibility. Second, he seeks out variations that respect the time-honored refined understatement championed by his soigné predecessors. Recent examples of successful modifications include the fly-front shirt, the velvet jacket, and the velvet bow tie.

Now that we’ve defined the gold standard, let’s take a look at its most common deviations today and see how they hold up to this benchmark. As we go, keep in mind that these variations are just relative guidelines since real-life outfits often incorporate traits from multiple categories.

The Black Business Suit

Photo by Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images

Proving the old adage that quantity does not equal quality, this is the most common tuxedo interpretation seen on the red carpet today. It appeals to timid novices’ unfamiliarity with traditional formalwear by replacing its unique traits with pedestrian equivalents found in formal business attire.

The standard features of the pseudo-tuxedo are notched lapels and multiple jacket buttons. The former draw the eye down away from the face (the intended focal point of any good tuxedo) and often suggest stooped shoulders. The latter cause the coat to button higher on the chest thus reducing the amount of visible white shirt and thus the contrast found in the ideal ensemble.

On their own these features can have relatively minor impact on an outfit’s overall elegance, particularly when compensated for with a traditional bow tie and waistcoat. The problem is that admirers of this interpretation will sometimes try to compensate for its banality with a suit-style vest that only serves to conceal the decorated shirt-front even more

Worse still, the distinctive bow tie is frequently switched out for a long black tie. At this point the wardrobe has essentially been demoted to the level of undertaker attire.

The Frat House Formal

Photo by Jean Baptiste Lacroix/WireImage

The frat boy approach is predicated on getting through the dressing process as quickly as possible to maximize time spent at the open bar.

Particularly popular among pledges is the forfeiture of a cummerbund or waistcoat. The shirt’s undecorated waist and the trousers’ working waistband are thus left completely exposed when the jacket is worn wide open (as frat boys are inclined to do). Even with the coat buttoned up, simply outstretching one’s arms or reaching into one’s pants pockets exposes a glaring white patch of shirt navel that breaks up the striking verticality of the black suit. Think of it as the formal version of plumber’s crack.

A less common but equally lazy shortcut is to opt for ordinary dress shirts. In this case sophisticated studs are replaced by run-of-the-mill buttons and a pure white bosom gives way to a single-layer shirt front discolored by its translucence.

The Prom Rental

Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images

Fans of prom wear are eager to dress properly but not yet sophisticated enough to view the tuxedo as anything more than a dressy Halloween costume. Consequently, said costume is poorly fitted and loaded with every clichéd novelty popularized in the 1980s: pleated shirts with flaccid attached wing collars, colored and/or patterned bow ties with cummerbunds or overly tall vests to match. White jackets are worn regardless of the season and are brightly bleached instead of the subtle cream or ivory that better complements most men’s complexions. It would never even dawn on the wearer to tie his own bow tie so he inevitably opts for the cookie-cutter uniformity of mass-produced pre-tied models.

This sartorial incarnation is relatively rare among style-conscious leading men and more likely to be seen at awards ceremonies for film technicians and professional athletes.

The Monochrome Mass

Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty Images

The least creative solution to appearing creative is the black-on-black ensemble. By stripping white out of the formal equation the outfit is robbed of its distinctive and striking contrast and reduced to a lifeless black monolithic swathe of fabric topped by a disembodied head.

The Couture Costume

Photos by Getty Images

The evening wear favored by fashionistas is more concerned with incorporating or inventing new trends than honoring the timeless conventions that define true formalwear. These digressions can range from subtle to outlandish depending on the whims of the couture houses or the individual dresser. The crowd aping the latest GQ stylings can currently be identified by suits with such tight fits, narrow lapels, and low-slung waists that they could be reasonably mistaken for women’s attire.

The Maverick Misfit

Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty Images

The domain of misguided mavericks and smug smart-asses. Most often the tuxedo is left intact while one or more peripheral articles are swapped with sophomoric alternatives such running shoes, T-shirts, and even toques. Foregoing a necktie in favor of an unbuttoned shirt is another favorite trick. Sometimes the suit itself will be bastardized in the form of unorthodox cuts or colors.

Look to music awards ceremonies, more so than the Oscars, for abundant examples of these sartorial missteps.

* * *

So there you have it: You’re now set to entertain/annoy your friends with your appreciation of the history and subtleties of men’s formalwear come Oscar night. Keep in mind though that this is not simply a field guide intended to help you spot the best and worst of men’s evening wear in the wild. It is also a practical primer for assembling a stellar outfit of your own should you find yourself an Oscar nominee or prom-night chaperone. Get it right and observers won’t need a reference manual to pick you out as the star attraction.