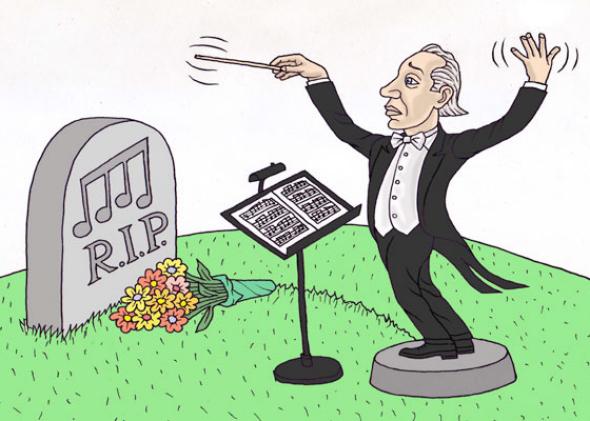

When it comes to classical music and American culture, the fat lady hasn’t just sung. Brünnhilde has packed her bags and moved to Boca Raton.

Classical music has been circling the drain for years, of course. There’s little doubt as to the causes: the fingernail grip of old music in a culture that venerates the new; new classical music that, in the words of Kingsley Amis, has about as much chance of public acceptance as pedophilia; formats like opera that are extraordinarily expensive to stage; and an audience that remains overwhelmingly old and white in an America that’s increasingly neither. Don’t forget the attacks on arts education, the Internet-driven democratization of cultural opinion, and the classical trappings—fancy clothes, incomprehensible program notes, an omerta-caliber code of audience silence—that never sit quite right in the homeland of popular culture.

The holiday season typically provides a much-needed transfusion. But the most recent holidays came after an autumn that The New Yorker called the art form’s “most significant crisis” since the Great Recession. Looking at the trend lines, it’s hard to hear anything other than a Requiem.

Let’s start by following the money. In 2013, total classical album sales actually rose by 5 percent, according to Nielsen. But that’s hardly a robust recovery from the 21 percent decline the previous year. And consider the relative standing of classical music. Just 2.8 percent of albums sold in 2013 were categorized as classical. By comparison, rock took 35 percent; R&B 18 percent; soundtracks 4 percent. Only jazz, at 2.3 percent, is more incidental to the business of American music.

What about the airwaves? There are only a handful of commercial classical music stations left in America. One of the last, KDB in Santa Barbara, Calif., was put up for sale in October after years of “six-figure losses.” Even public classical radio is in trouble. The number of noncommercial classical radio stations—on the air and online—has risen. But much of that growth is due to commercial stations switching to a public format. Actual listenership continues to decline.

And some public classical stations have ditched the music. One such station, WUIS in Illinois, added an online classical channel after switching the main station to talk and news. As the station’s manager put it, “[C]lassical radio is one of those things that’s slowly going away.” Sirius XM, the satellite and online radio provider, has nine jazz channels, 20 Latino channels, and eight Canada-themed channels—but only two traditionally classical stations. One, called Symphony Hall, has 3,500 Facebook likes. Sirius’ all–Pearl Jam channel has 11,000; their D.J. Tiesto-curated channel has 89,000.

Now let’s look at classical concerts. Live classical music is less commercially viable than ever. Attendance per concert has fallen, according to Robert Flanagan, an emeritus professor at Stanford. But “even if every seat were filled, the vast majority of U.S. symphony orchestras still would face significant performance deficits.” Live orchestral music is essentially a charity case. A Bloomberg story on the recent wave of orchestra bankruptcies (an unheard-of phenomenon outside of the U.S., says Flanagan) notes that by 2005, orchestras got more money from donations than from ticket sales. The New York City Opera, once hailed as the “people’s opera,” filed for bankruptcy in October. If the “people” want opera, they’ve got a funny way of showing it.

Non-orchestral performances are harder to track. But Greg Sandow, a musician and writer, reports anecdotal evidence for a decline in chamber music. There’s also grim data from the NEA that shows the percentage of adults who attended a classical concert (even one per year) declined from 13 percent in 1982 to 11.6 percent in 2002, and 9.3 percent in 2008. A further decline to 8.8 percent in 2012 was not considered statistically significant, though significant declines in those years occurred in the 35–44 and 45–54 age bands.

Which brings us to demographics. Sandow notes that back in 1937, the median age at orchestra concerts in Los Angeles was 28. Think of that! That was the year, by the way, that Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony’s summer festival, was founded. I grew up near Tanglewood and had various summer jobs there in the 1990s. When I worked at the beer and wine stand, I almost never carded anyone.

Sandow and NEA data largely back up what I saw on Tanglewood’s fabled lawns two decades ago. Between 1982 and 2002, the portion of concertgoers under 30 fell from 27 percent to 9 percent; the share over age 60 rose from 16 percent to 30 percent. In 1982 the median age of a classical concertgoer was 40; by 2008 it was 49.

If classical music was merely becoming the realm of the old—an art form that many of us might grow into appreciating—that might be manageable. But Sandow’s data on the demographics of classical audiences suggest something worse. Younger fans are not converting to classical music as they age. The last generation to broadly love classical music may simply be aging, like World War I veterans, out of existence.

What about making music? In 1992, 4.2 percent of American adults reported performing or practicing classical music at least once in the previous year.

By 2012, the number had dropped to 2 percent (compared with, say, the 5 percent of Americans who reported they created “pottery, ceramics or jewelry.”)

What about music education? The story of how the ax of school funding cuts falls first on arts education, especially in poorer school districts, is an old one now. Yet despite all the studies that show the broad benefits of music education, many school systems will now have “no music specialists serving elementary schools,” notes James Catterall, a professor at UCLA. As for adult education, when the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, Mass., decided to shutter its amateur education program, an outraged citizenry compared its importance to that of a hospital emergency room. But even the picketing, petition-signing populace of the People’s Republic couldn’t stop the program from closing.

Finally let’s look at the general cultural positioning of classical music. This is harder to quantify, but there’s some useful data. Many publications no longer retain full-time classical music critics. Yvonne Frindle, a music blogger, notes that Time has featured 64 classical figures on its cover—but the vast majority before 1956 (though Bach made the cover in 1968). The last, featuring Vladimir Horowitz, came in 1986. Today the notion that a pianist could culturally sideline a story about aircraft carriers sounds nothing short of quaint.

Classical music does retains overtones of, well, classiness. But in contemporary America, that’s arguably its biggest problem. Take the popular sitcom Modern Family. In one episode, Phil and Claire are mortified at the thought of attending a cello performance by Alex, their nerdy daughter. They panic and invent dinner plans with fictitious friends, “the Flendersons.” It turns out Alex is in fact playing cello for a rock band. Her mom and sister are pleasantly surprised.

Or take Manny—the show’s old-beyond-his-years kid who composes poetry and writes novels. Naturally, he loves classical music. It’s the perfect American shorthand for peer alienation. And note the joke. Classical music isn’t like broccoli—something Manny’s too young to love. He’s listening to something even “regular” adults don’t like. “Oh, crap!” says Jay, Manny’s stepdad, when he finds out a concert is Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (one of classical’s rare actual hits) not Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. Then he walks “like a man” to the nearest bar.

Jay, and America, are unlikely to back proposals to tax the NFL in order to fund symphonies. But are there any bright spots at all? Despite the worries over music education, instrument purchases for schools have remained fairly constant at just under one instrument for every 50 kids, each year. That’s not a lot, and instruction time and quality is another question. But at least instruments are physically in the classrooms.

And it’s not as though the classical music world isn’t trying to address its image problems. Kudos to Groupmuse, for example, which arranges informal but high-quality live classical performances in Boston-area private homes, and markets them to a young audience (“halfway between a chamber music concert and a house party … Jam out on the air-violin if that’s your thing!”). Greg Sandow also notes that America’s population growth will continue to buy time for classical music. Some strong institutions, like Tanglewood, will endure—maybe even thrive—on a declining share of a growing pie.

Myself, I cling to the forlorn hope that classical music has been down for so long, it must somehow be due for a comeback. More realistically, though, I’m hoping for Jeff Bezos to step in. He recently described Amazon as a symphony of people, software, and robots. Maybe he’d like a struggling orchestra to go with his newspaper.