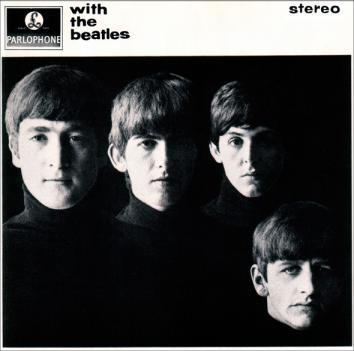

On Nov. 22, 1963, two very good things happened along with one unspeakably awful thing. The fact that both A Christmas Gift for You From Philles Records (later renamed A Christmas Gift for You From Phil Spector) and With the Beatles both came out on the same day as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy is one of the most twisted ironies in the history of popular culture. Christmas Gift is the iconic Christmas pop record for all time and one of the most ebullient collections of music ever assembled. With the Beatles is one of the most important albums by the most important band in history. Not a bad day, except that it was the worst day.

Beatle literature contains a long tradition of linking the band’s American breakthrough to the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination. Lester Bangs, in a famous essay on the British Invasion from The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll, wrote that “[i]t was no accident that the Beatles had their overwhelmingly successful Ed Sullivan Show debut shortly after JFK was shot,” a choice of words that might as well put John and Paul in the book depository. Ian MacDonald, whose Revolution in the Head is the gold standard in Fab Four criticism, argued that “When Capitol finally capitulated to Epstein’s pressure and issued ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ [in December of 1963], the record’s joyous energy and invention lifted America out of its gloom, following which, high on gratitude, the country cast itself at the Beatles’ feet.”

History is more fun if it happens in turning points. Dylan goes electric, The Velvet Underground and Nico starts 30,000 bands, Michael Jackson moonwalks on Motown 25—all are Moments When Everything Changed. No event has endured more of this than the Beatles’ arrival in the United States in February of 1964, where they performed before 70-some million Americans on the Ed Sullivan show, soothed an injured nation in the wake of the assassination, and saved rock and roll in the process. As Bob Spitz, the author of a celebrated and enormous biography of the band, put it a while back, “The Beatles changed music forever. They took rock ’n’ roll from a medium that was about cars and girls and gave it context, interesting chord changes and true musicianship.” Variations on this abound in Beatle hagiography.

The Beatles absolutely changed music forever, but the rest of that statement is utterly ludicrous. The “true musicianship” bit is barely even worth debunking, but every second of this (1958), this (1961), or this (1962) should suffice. As for the “cars and girls” claim, the first Beatle song that was definitely not about cars or girls was “Nowhere Man,” which appeared in the U.K. on Rubber Soul in late 1965 and in America in early 1966. Here are three extremely famous songs that came out before then: Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street” (1964), Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” (1964), Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (1965). Not one is about cars or girls.

The problem with these turning-point narratives, which often invoke the Kennedy assassination for its epochal gravitas, is that they’re willfully dismissive of all that came before. They imply that the Beatles rendered a whole pre-existing world of popular music instantly obsolete or—even more insidiously—turned it into primitive source material for them to improve upon. And in case you’ve started to wonder, most of the writers making these claims are white men; most of the artists they’re so blithely disinterested in are not.

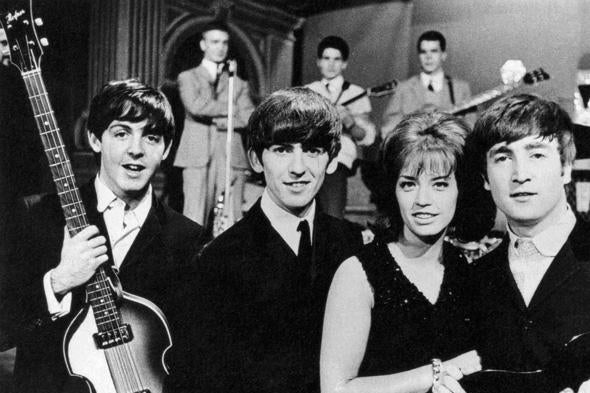

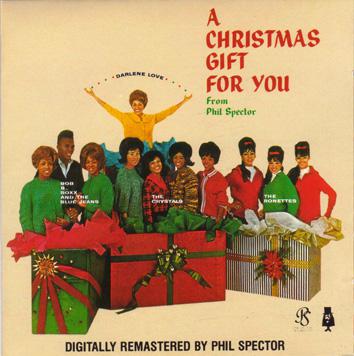

Which brings us to Philles Records, which released one of the great rock and roll albums of all time in the United States the same day the Beatles did so in the U.K., a day when the world’s eyes, ears, and thoughts were squarely focused on Dallas. Throughout 1963 Phil Spector’s label, most famous for young African-American female singers like the Ronettes, the Crystals, and Darlene Love, had been making electrifying art. Just two months prior to the Kennedy assassination Philles had released the Crystals’ “Then He Kissed Me,” which isn’t about cars but is most certainly about a girl (the incomparable LaLa Brooks) and is one of the finest songs about romantic anticipation ever written.

Christmas Gift was Spector’s pièce de résistance, the apex of his legendary “Wall of Sound” period. The excesses of the holiday gave pop’s greatest maximalist carte blanche to make the record of his wildest dreams. Today, Christmas pop is a fatigued genre, but that’s partly because Christmas Gift left everything in its wake feeling vaguely redundant. Tracks like the Crystals’ “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” and the Ronettes’ “Sleigh Ride” are chestnuts roasted with C-4, and the album’s greatest track, Darlene Love’s “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home),” is less a Christmas song than a three-minute aria of regret and hope.

Courtesy of EMI

The album was also a flop. Despite bearing the name of one of the most popular labels in America, A Christmas Gift for You From Philles Records didn’t sell, and Spector would blame the assassination for its failure. (Leave it to Phil Spector to frame the defining tragedy of the last 50 years in terms of record sales.) But there are other reasons why Christmas Gift might have flopped, the biggest being its format. In 1963 rock and roll was a singles medium: Philles had released a total of only five LPs prior to Christmas Gift, none of which were successes. In fact, it was the Beatles themselves who would be most responsible for turning the music into an album-oriented form, when they audaciously released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band without a single in 1967. It was only in later years that Christmas Gift’s songs became iconic, and the LP finally received its day in the sun in the early 1970s, when it was reissued by Apple Records—a company founded by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr, four of Spector’s girl groups’ biggest fans. Christmas Gift, a conceptually unified, perfectly sequenced long-playing work of rock and roll, might have failed because it was ahead of its time.

If the musical side of the Beatles/JFK turning point seems bogus, the historical side feels like mythologists leaning too hard on coincidence. But what do I know? I wasn’t there. So I asked Greil Marcus, who wrote the Beatles entry in the same Rolling Stone Illustrated History that contains Lester Bangs’ claim. Marcus pointed out that several Beatles’ singles had been released in the States prior to the assassination but hadn’t (yet) become hits, victims of faulty or indifferent promotion. “ ‘Please Please Me’ was a local hit in San Francisco on Top 40 in the spring of 1963, by some group called ‘The Beetles,’ or whatever, and I loved it, but never wondered about who did it,” he told me in an email. “I can also say that for me there was never at the time any connection between the malaise or shock over the assassination and the arrival of the Beatles.”

Courtesy of Robert Freeman/Parlophone/EMI

The Beatles–JFK mythology also strikes me as a distinctly American affair. After all, by November of 1963 the Beatles were already huge in England, and With the Beatles had sold half a million copies in advance. But again: What do I know? So I asked British Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn, author of the exhaustive three-part chronicle The Beatles: All These Years (the first volume of which has just been released) and a man who probably knows more about the Beatles than anyone besides Paul and Ringo. Did anyone in England in November of 1963 connect the events in Dallas with the release of the biggest album in the history of British music? “No prominent instances at all, not even insignificant ones,” Lewisohn told me. “The coincidence only became apparent with hindsight.”

The fact that With the Beatles and A Christmas Gift for You From Phil Spector were released on the same day is a coincidence. Were they released on any other day it would be one of the happiest coincidences in all of music; instead it’s one of the most perverse. But it’s still a remarkable convergence, and an instructive one for picking apart some of the myths we’ve told ourselves. In 1963 you could stroll into the new releases section of a record store and find Marvin Gaye’s “Can I Get a Witness,” Martha and the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave,” the Impressions’ “It’s All Right,” the Crystals’ “Da Doo Ron,” and the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.” And if you still had enough for an LP you could wander over to the folkaisle and grab The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Fifty years later all those titles hold up awfully well, and the music scene on Nov. 22, 1963, was a vibrant place that the Beatles were about to make a whole lot more vibrant. Just because something wonderfully new comes along doesn’t mean that everything else has to suddenly be old.