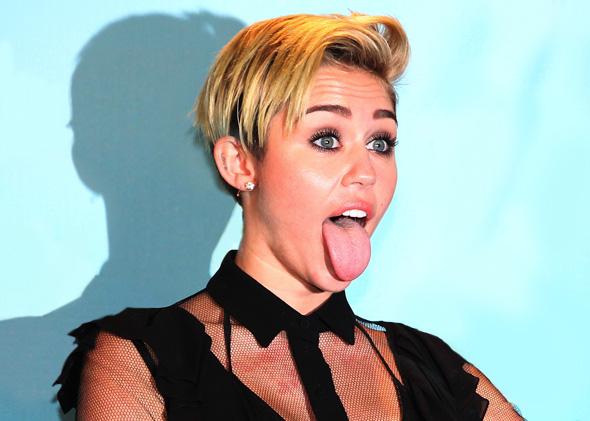

Even before Miley Cyrus’ chart-topping album Bangerz was released last week, devotees were already poring over the leaked lyrics, searching for clues as to how she was coping without former beau Liam Hemsworth. Sure enough, buried amid the Auto-Tuned swoons of “My Darlin’ ” was a line that seemed to tell it all: “I can’t breathe without you, without you as mine.”

Either recording booths in the 21st century need to come equipped with oxygen masks, or today’s lyricists tend to brood over their breakups in the intensive care unit. Presenting an inability to breathe has become a ubiquitous songwriting crutch, an insipid shorthand to express longing or describe an emotional trauma. It’s my candidate for the laziest lyric of the century.

This particular pet peeve first colonized my brain when I caught the chorus to Taylor Swift’s 2008 ballad “Breathe”: “And I can’t breathe without you, but I have to.” It’s true, you do! Suddenly, whenever a top 40 radio station hit the dial, the proclamations of asphyxiations came fast and steady, and I began amassing a “can’t breathe” case file. True, the same could be said of familiar tropes like tacking on that a scene is transpiring in the rain to make the setting more urgent or melancholy, or that yes, you own the night. And where would all the Mumford-style bands be without all that blood they bleed? But I contend there’s something uniquely irritating about “can’t breathe.”

What I find so odd about this particular lazy metaphor is that the act of singing the lyric disproves its intent. Writer’s block yields piles of unused paper. Painters in a rut neglect their canvases. But a singer is actually using the air in his or her heartsick lungs to express, and then dispel, this thoroughly exhausted announcement of breathlessness. The instant the line is uttered, the fallacy is exposed, and the moment deflates.

On “Jealousy,” Will Young drops to his knees when he feels like he can’t breathe. Leona Lewis, a winner on The X Factor, sings the eponymous lyric dozens of times in “Can’t Breathe,” but at least acknowledges that this separation of soul mate and oxygen supply spells doom (note the shout-outs to getting weak and feeling like death is close). Michelle Branch is less dramatic; she limits her bated breath to counts of 10. Tom DeLonge of Angels & Airwaves gave the expression a slight twist with his emo inflection, ratcheting the annoyance factor to unseen heights.

How is it that a set piece as emotionally charged and relatable as withdrawing to dress your wounds after a breakup has funneled down to the “can’t breathe” trope? Consider the lyrical complexities of a standard like “Hello Walls,” written by Willie Nelson in 1961, in which the despondent crooner resorts to conversations with inanimate objects while holed up in his bedroom, asking the window if that’s rain or a teardrop streaking down the pane. Now there’s an image fully rendered. A contemporary ballad like Frank Ocean’s “Pyramids” also finds a man wallowing in a vacant room, wondering where his partner spends her nights, but the lyrical composition benefits from a wide scope backed by hyperspecific details, opening in the age of hieroglyphs before descending into VCR snow.

Perhaps the clearest explanation for how we arrived at this “can’t breathe” cul-de-sac can be found in John Seabrook’s recent New Yorker profile of Lukasz Gottwald. Gottwald, also known as Dr. Luke, is the 40-year-old hit-maker who came to worldwide prominence in 2004 after co-writing Kelly Clarkson’s “Since U Been Gone,” the power-pop anthem capped by the chorus “Since you been gone, I can breathe for the first time.” (Clarkson, it should be noted, is a multiple offender; in “Addicted,” she sings that she “can’t breathe” after a “leech” of an ex sucks the life from her.) Gottwald tells Seabrook he’s never finished a book, and that he finds lyric writing “not fun,” preferring to farm out that responsibility to lyricists like Bonnie McKee, who explains to Seabrook that the process is “very mathematical. A line has to have a certain number of syllables, and the next line has to be its mirror image.” In this paradigm, it’s understandable that familiar lyrics get slotted into well-trod emotional cues. The formula is certainly a winning one; Gottwald has had a hand in “as many No. 1s in 2010 as the Beatles had in any single year.”

Perhaps this phenomenon of syllables over substance isn’t quite so toxic. What I find the most virtuosic vocal performance of the year, the guest verses by Bone Thugs-n-Harmony on the ASAP Ferg track “Lord,” is a monument to syllable-by-syllable construction. And when it comes to writers resorting to the can’t-breathe crutch, few of us are immune. After stumbling out of a screening of Gravity earlier this month, like countless other thoroughly satisfied, shell-shocked film critics I retreated to my laptop, declaring the film to be “breathtaking.”

With that off my chest, I can breathe for the first time.