I first met Lou Reed about 10 years ago, at a benefit in New York. Reed was sitting next to his partner, Laurie Anderson, and fiddling with a Palm Pilot. He was wearing a grey blazer covered with black furry patches, in a sort of random pattern, and tight blue jeans stuffed into black cowboy boots. I couldn’t help but peer over Reed’s furry shoulder—and his rather imposing mullet—watching him paging through menu screens on the PDA at an impressive clip. I thought of the black-and-white Velvet Underground poster that hung in my kitchen for years, and the image of Reed as a champion of down and dirty minimalism, of raw three-chord rock, and New York cool. And there he was, Mr. Rock ’n’ Roll Animal, fiddling with a Palm Pilot.

Reed was always a tech boffin, a part of his history that often gets glossed over. Read old interviews and he talks at excruciating length about the technical aspects of recording. “I spend a lot of time researching,” he told Simon Reynolds in 1992. “You could call it studying. I ask, ‘Why does digital do that? What’s the analog-to-digital conversion process? Are the filters better now?’ It goes back to the wood in the guitar, which pickups to use.”

When I heard that Lou Reed died, I was in London, fiddling with a mobile phone as the streets filled with rain. I couldn’t believe that Reed was dead; he was an ur-text for rock ’n’ roll, for New York, for my childhood. By the time I was 17, my teenage friends and I had memorized every Velvets song; we knew all the outtakes, live versions, and B-sides. We covered our house in aluminum foil to get it to look like the Factory; we put a strobe light in the bathroom, where “Venus in Furs” played on loop. My friend Blake donned a handmade Andy Warhol wig and I practiced a Nico accent. Reed was like a family friend to us; we yelled at him through the stereo. We chuckled at songs like “Lady Godiva’s Operation,” relishing the moment when Reed’s voice cut in, complementing John Cale’s elegant Welsh lilt with the grace of a thousand heavy rocks. When we burned out on the VU, we tuned into David Bowie, and to Reed’s solo output—from Transformer to Berlin to The Blue Mask. My personal favorite was Reed’s critically panned 1975 opus Metal Machine Music.

The album—once denounced by Rolling Stone as the “tubular groaning of a galactic refrigerator”—was Reed’s masterpiece. It was Reed at his most aggressive—four sides of earsplitting feedback, spread over two LPs—and Reed at his nerdiest. Cale had turned Reed on to the power of the drone and to experimental electronic music, and Metal Machine Music was Reed’s ultimate synthesis of the two. “No Synthesizers,” Reed proudly proclaimed on the back of the LP, writing that the album displayed “drone cognizance and harmonic possibilities vis a vis Lamont [sic] Young’s Dream Music.” He told Lester Bangs that bits of Vivaldi, Beethoven, and other classical composers were embedded in its chaos. “This record is not for parties/dancing/background romance,” Reed wrote in the Metal Machine Music liner notes. “This is what I meant by “real” rock, about “real” things. No one I know has listened to it all the way through including myself. It is not meant to be.”

I fell asleep to Metal Machine Music every night for years when I lived in New York City, harnessing the album’s punishing waves of feedback to drown out the cacophony of the streets below. After a while, I found the album soothing, even nourishing; there was something cosmic about it, something timeless. I somehow knew that Lou felt the same way. The only thing heavier than the feedback was the hubris—Metal Machine Music was Reed at his most ridiculous and conceptual extreme. I still laugh when I think of the last line of Reed’s snarling, obnoxious liner notes: “My week beats your year.”

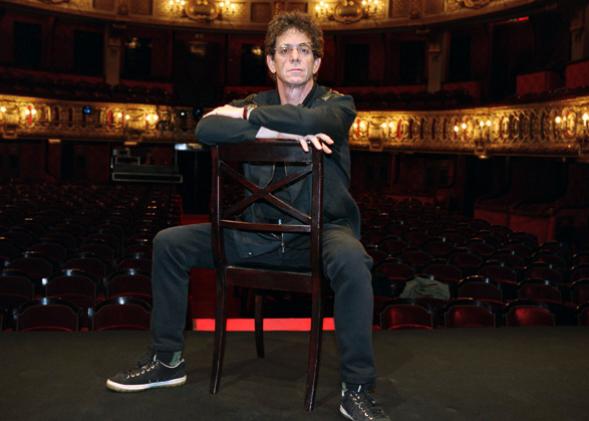

Reed packed more life into those weeks than most of us ever will. I remember staring at his face in awe, studying those deep character lines and ridges, a face as tough as a piece of old leather.

“I really disliked school, disliked groups, disliked authority,” Reed once said. “I was made for rock ‘n’ roll.” It wasn’t an entirely true statement; as Slate’s Carl Wilson notes in his appreciation, Reed’s classes with the poet Delmore Schwartz at Syracuse University were central to his aesthetic, and he was most famous as part of a group. But part of Reed’s brilliance was in disliking almost everything—in cutting through the “glop”, as he would say, in distilling music down to its essence. He had little tolerance for bullshit. “Repetition is so fantastic, anti-glop,” Reed wrote in the pages of Aspen in 1966.

“Listening to a dial tone in Bb, until American Tel & Tel messed and turned it into a mediocre whistle, was fine. Short waves minus an antenna give off various noises, band wave pops and drones, hums, that can be tuned at will and which are very beautiful. Eastern music is allowed to have repetition…Andy Warhol’s movies are so repetitious sometimes, so so beautiful. Probably the only interesting films made in the U.S. Rock-and-roll films. Over and over and over. Reducing things to their final joke. Which is so pretty.”

It wasn’t often that Reed called his own music pretty, but most of his music was pretty in spite of itself. The stark, brutal lyrics heightened the beauty; it made the moments of light feel lighter. “Just the verbal and musical zeitgeist that Lou created—the nature of his lyric writing had been hitherto unknown in rock, I think,” Bowie once said. “He gave us the environment in which to put a more theatrical vision. He supplied us with the street and the landscape, and we peopled it.”

By carving out all the negative space, Reed created the environment for thousands of bands to bloom. He stood for many things: New York City, minimalism, repetition, feedback, poetry, darkness. But most of all, he defined what rock ’n’ roll could be: not just for himself, but for all of us.

For more on Lou Reed, read Mark Joseph Stern on whether the singer was the first out rock star and Rob Wile on how Reed helped bring down communism in Eastern Europe. Also, check out this great PBS documentary on Reed.