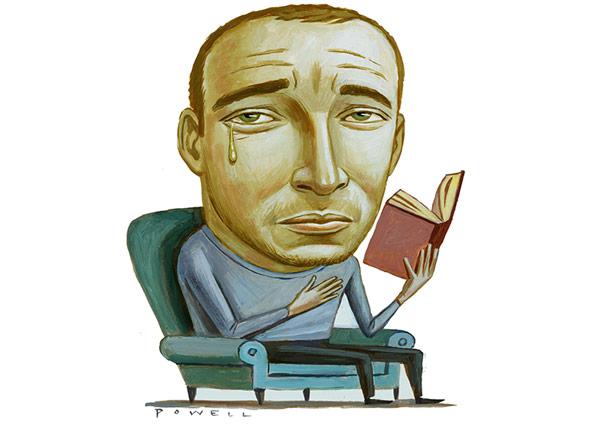

Does reading fiction make you a better, less self-absorbed person? You read because you are interested in the broad sweep of human experience, and because you want to gain access into the narrow sanctum of specific otherness—to feel Anna Karenina’s recklessness and desperation, or know the shape and weight of Ahab’s obsession, and thereby something of humanity itself. But in order to make any headway with a novel, you need to grant yourself a leave of absence from human affairs, to sequester yourself in a place where you are sheltered from the demanding presence of other people. Opening a novel might be a kind of exposure to the world beyond the self, but it’s one that necessarily involves a foreclosure against it too. A life spent reading is, among other things, a life spent alone.

The idea that reading is an ethically salutary pursuit gets more appealing the more time you spend doing it. There’s something basically reassuring about the notion that you might be a better person—not just intellectually, but morally—for having read a lot of literature. I’ve just recently moved house, a large part of which undertaking involved the handling and sorting and packing and schlepping of books. As I took the books off the shelves and put them into cardboard boxes—and again as I took them out of those boxes and put them back on shelves in a different house—I found myself thinking about what all the time spent reading them added up to. A lot of these books I’ve forgotten almost everything about; all that is left to me of Oblomov, say, is a chubby Russian aristocrat in a dressing gown (was he even actually chubby?), and basically all I remember of Don DeLillo’s Libra is that it was about Lee Harvey Oswald and that it was brilliant. I found myself trying to quantify the residue of all this reading; what was it that it left behind, and how had it changed me, if at all? There was, surely, some cumulative effect, some way in which I could be said to be a better or wiser person for it. But all I could think, really, was: Christ, if all this reading has made me a better or wiser person, I’d hate to think what kind of monster I’d be without it.

Earlier this month, a research paper was published in the journal Science which put forward evidence that social skills are improved by the reading of fiction—and specifically the high-end stuff: the 19th-century Russians, the European modernists, the contemporary prestige names. The experiment, conducted by psychologists Emanuele Castano and David Comer Kidd, found that the subjects who read extracts from literary novels, and then immediately afterward took tests measuring empathy, social perception, and emotional intelligence (looking at photos of people’s eyes and guessing what emotions they might be going through), performed significantly better on the tests than other subjects who read serious nonfiction or genre fiction. Their basic finding was that reading literary fiction, and literary fiction alone, temporarily enhances what’s known as Theory of Mind—the ability to imagine and understand the mental states of others.

The reaction to this was widespread and, as you’d expect, overwhelmingly pleased. Louise Erdrich, whose novel The Round House was used as an example of literary fiction in the experiment, was quoted in the New York Times’ report on the research. “This is why I love science,” she said; the psychologists had “found a way to prove true the intangible benefits of literary fiction.” Finally, science has given its approval to one of the literary world’s most cherished ideas about the value of literature. Even though the study only measured extremely short-term benefits of exposure to small amounts of literary fiction, it was largely taken to stand for a wider truth about the morally improving effects of the stuff, the notion that it makes you a better, more empathic person.

And this, obviously, is nothing new. Although the novel has, throughout its history, often been subject to a kind of self-reflexively ironic anxiety about the dangers of excessive investment in fiction (see Don Quixote, Northanger Abbey, and poor old Emma Bovary for further details), the consensus among writers has generally been that imagining ourselves into fictional minds and lives is something that increases our moral faculties—a practice that grows our capacity for empathic engagement with the minds and lives of actually existing other humans. Our modern concept of empathy comes from the German term einfühlung, which means “feeling into,” and it makes sense that we would associate this quality with the literary capacities of affective projection.

Novelists have historically tended to be invested in the notion that narrative art can jolt us out of our selfish complacency and into a deeper sense of the experiences and sufferings of other people. George Eliot, in her essay on German realism, wrote that “the greatest benefit we owe to the artist, whether painter, poet, or novelist, is the extension of our sympathies. Appeals founded on generalisations and statistics require a sympathy ready-made, a moral sentiment already in activity; but a picture of human life such as a great artist can give, surprises even the trivial and the selfish into that attention to what is apart from themselves, which may be called the raw material of moral sentiment.” And here’s David Foster Wallace saying something quite similar, if more pessimistic about the degree to which genuine connection is possible: “We all suffer alone in the real world. True empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with their own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside. It might just be that simple.”

So this research is, in one sense, a pretty trivial reiteration of something that has long been taken as a basic article of faith by many people for whom literature is more than mere escapism. The important difference here, obviously, is that it is science that is telling us this about literature, and not literature itself—and so the idea seems, rightly or wrongly, more like something you can take to the bank. But although I believe that literature is a huge and indispensable aspect of our humanity—that books are, as Susan Sontag put it, nothing less than “a way of being fully human”—I felt that there was something oddly diminishing, and perhaps even absurd, in the notion of bringing literature to account in this way. Of sitting people down and giving them a chunk of Chekhov to work their way through, and then measuring the short-term uptick in their ability to read people’s facial expressions. (And does the ability to correctly read emotions from pictures of faces really translate into anything like real empathy? I can recognize that you are suffering, but not really feel that recognition act with any force upon myself, let alone lead me into doing anything about it.)

I’m equally ambivalent about the question of whether reading literary fiction really does make you a better person—not just about what the answer might be, but whether the question itself is really a meaningful one to be asking at all. It implies a fairly narrow and reductive legitimation of reading. There’s a risk of thinking about literature in a sort of morally instrumentalist way, whereby its value can be measured in terms of its capacity to improve us. There was a weirdly revealing quality, for instance, in the language that the Atlantic Wire used in reporting on similar research conducted in the Netherlands earlier this year. “Readers who emotionally immerse themselves with written fiction for weeklong periods,” David Wagner wrote, “can help boost their empathetic skills […] Gauging the participants’ empathetic abilities and self-reported emotions before and after such reading sessions, they found that the fiction readers got more of an emotional workout than the nonfiction readers.” It’s possibly unfair to put too much pressure on one writer’s choice of words in framing the discussion (particularly in a roundup blurb), but it hints at a certain view of literature that is implicit in this way of thinking about it—literature as PX90 workout for the soul, as a cardio circuit for the bleeding heart.

We have, I think, an anxiety about the place of literature in our world, about the usefulness of reading fiction. If we can answer the question of why we read with the empirically verifiable assertion that it makes us more socially attuned, then that seems to give literature an identifiable job to do, a useful function in our lives. Perhaps this is the case; perhaps reading Kafka or Woolf or Naipaul does make you a better, more empathic person. (Though what about your hardline literary misanthropes, by the way—your Bernhards, your Houellebecqs, your Célines? Do we gain anything in moral aptitude by reading these dreadful old bastards, and, if we don’t, is doing so somehow less worthy of our time?) But even if it didn’t, even if reading made you a worse person—if you found yourself too engrossed in Karl Ove Knausgaard to take your bored children to the park—reading would be no less vital an activity. I don’t know whether all those boxes full of books have made me any kind of better person; I don’t know whether they’ve made me kinder and more perceptive, or whether they’ve made me more introspective and detached and self-absorbed. Most likely it’s some combination of all these characteristic, perhaps canceling each other out. But I do know that I wouldn’t want to be without those books or my having read them, and that their importance to me is mostly unrelated to any power they might have to make me a more considerate person. This, at least, is what I plan to tell my wife next time she complains about my keeping her awake by reading too late.