Soon after joining the staff of The Simpsons, Bill Oakley made a strange discovery. Hiding in a cluttered corner of the show’s writers’ room, “under a whole bunch of crap,” he says, was a 5-inch thick stack of dot matrix printer paper. (This was 1992.) The mysterious, perforated pile contained thousands of neatly typed comments. Oakley remembers sifting through the bundle and thinking, What is this?

The copious notes were posts culled from alt.tv.simpsons, an online newsgroup populated by some of the series’ hardcore fans. To Oakley, this was a revelation. At the time, outside feedback consisted of little else but ratings. “And the ratings never had anything to do with the quality of the episode,” says Oakley, a longtime writer and producer on the show. “They had to do with what was on opposite it, or what the weather was like, or whatever.”

Alt.tv.simpsons wasn’t just a breezy message board powered by a thousand monkeys working at a thousand typewriters; it was brimming with recaps, reviews, and minutiae. The type of intricate, serialized analysis found on alt.tv.simpsons—a.t.s. to its regulars—has been unexpectedly influential. Its ethos can be seen in modern television coverage, which is dominated by an endless stream of point-by-point episode breakdowns. “At its best, new-school TV writing is brainy and inquisitive, thoughtful commentary borne out of a fanatical attention to detail,” Slate’s Josh Levin wrote in his 2011 assessment of the changing medium. “But hypervigilant criticism, written by obsessive fans for obsessive fans, isn’t necessarily an unmitigated force for good.”

Long before the rise of TV recap culture, its best and worst elements commingled in the alt.tv.simpsons laboratory. The content ranged from meticulous (a list of the show’s blackboard and couch gags) to smart (a later-proven theory that Maggie shot Mr. Burns) to overcritical (in the middle the unimpeachably great Season 4, somebody started the thread “Simpsons in decline?” in which one poster claimed that “Marge vs. the Monorail,” a classic episode, “had 0 good quotes”) to offensive (e.g., “Lisa has a proto-dyke Marxist Jew agenda”). As an a.t.s. tutorial wisely explained, “These are called trolls, and even alt.tv.simpsons isn’t immune to them.”

Just as Lost and Gossip Girl recaps would later be perused by showrunners and execs for clues as to the audience’s response, the exhaustive digital repository of alt.tv.simpsons attracted the attention of the cartoon’s creative team. Another Simpsons writer/producer, David X. Cohen, couldn’t quite wrap his head around the lengths the online community went to express its intense devotion to OFF (that’s alt.tv.simpsons shorthand for Our Favorite Family, aka the Simpsons). “I made the discovery in those early days that people only post to the Internet when they have an extreme point of view,” Cohen says now. And in 1994, Simpsons creator Matt Groening admitted to the Philadelphia Inquirer that he frequented alt.tv.simpsons. “Sometimes,” he said of the message board’s users, “I feel like knocking their electronic noggins together.”

When “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire,” the series’ full-length premiere, aired on Dec. 17, 1989, Gary Duzan was a junior at the University of Delaware. The computer science student soon figured out a way to celebrate his new favorite show. He often explored Usenet, a pre–World Wide Web network of newsgroups dedicated to different topics. Newsgroups were split into hierarchies. (For example, comp. covered computers, sci. covered science, and soc. covered social issues. Alt. encompassed “alternative” subjects, including TV programs like The Simpsons.) If cult classics like Dr. Who and Star Trek had their own newsgroups, Duzan figured, then “The Simpsons certainly should have one.” So, in March 1990, he created alt.tv.simpsons. On its first day of existence, about 100 posts poured in. “People found the thing right away,” Duzan says.

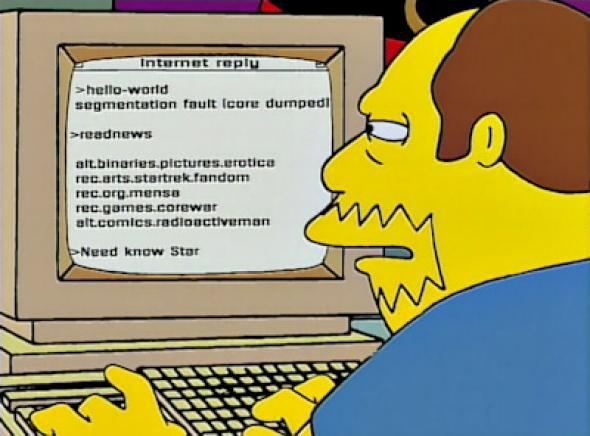

This was mildly remarkable, considering that Internet access was still so limited. Early alt.tv.simpsons occupants tended to be college kids and unusually tech-savvy Simpsons obsessives. Prolific poster Don Del Grande discovered a.t.s. only after logging on to the Internet through a university-provided Unix shell account. Unix was a completely text-based operating system. That meant no Evil Homer GIFs to look at or even a browser with which to navigate. There were just words on a screen.

Yet by December 1997, Wired was reporting that users posted an average of 737 messages daily on alt.tv.simpsons. It became the meeting place for the show’s most discerning fans. After grabbing a copy of the new TV Guide every Monday during his lunch break, Del Grande would read up on the week’s Simpsons episode and quickly post about it. “I always wanted to know what was going to be on TV as soon as possible,” he says now. “I’m also the kind of person who believes, ‘I can’t be the only person who would like this information, so I might as well tell as many people as possible whom I think I would want to know.’ ”

Newsgroups were havens for television junkies like HitFix’s Alan Sepinwall, an insightful and prolific purveyor of contemporary TV coverage. These days, he reviews 10 to 15 shows per week. In the mid-1990s, he was occasionally visiting alt.tv.simpsons and regularly posting write-ups on alt.tv.nypd-blue. On newsgroups, he says, “I definitely engaged with hardcore TV fans in the same way I would years later on blogs and message boards. In fact, I started blogging because I missed that level of direct engagement with other like-minded viewers and fans from the Usenet days.”

In the case of The Simpsons, the conversation wasn’t just among fans. After he started working on the show, Oakley purchased a primitive dial-up Internet account (he compared it to what Matthew Broderick’s character used in War Games) and began checking out alt.tv.simpsons. He didn’t just lurk, either. He engaged. On July 25, 1993, for example, Oakley posted detailed episode information for the then-upcoming Season 5. For fans of the show, it’s an amazing time capsule.

According to Oakley’s rundown, the episode “Homer and Apu,” which would air the following February, initially may have included an appearance by David Bowie. (James Woods actually showed up.) The “NOT YET WRITTEN” portion of the post mentioned the working titles of future classics, including “Lisa’s Hockey Team,” “Summer Swimming Pool/Rear Window Parody,” and “Bart Gets a Girlfriend.”

In hindsight, there’s something quaint about a writer from a hit TV series happily feeding inside information to people on a message board. But Oakley shared their love of The Simpsons. Had he not ended up writing for the show, he says, “I would’ve been one of them.”

The forum’s seemingly high collective IQ also intrigued Cohen. In May 1995, after “Who Shot Mr. Burns?” aired, he says an alt.tv.simpsons user was the first person to solve the mystery. (Alas, the poster didn’t win Fox’s official “Who Shot Mr. Burns?” contest because it required entering via sponsor 1-800-COLLECT.) Cohen, who has a master’s degree in computer science from University of California–Berkeley, also enjoyed hiding geeky Easter eggs in episodes just to see what kind of reaction he’d get. In the background of “Homer3,” a computer-generated segment in “Treehouse of Horror VI,” Cohen planted an equation that appears to—but doesn’t actually—disprove Fermat’s Last Theorem. As Cohen expected, alt.tv.simpsons seized on it. “They also put up a not-quite-true counter-example to Fermat’s Theorem,” Joel Rubin posted on Nov. 7, 1995. “No proof, though. I guess they didn’t have enough space in the margins of the film.”

There’s little doubt that the denizens of alt.tv.simpsons were smart. “You had to have a degree in computer science or you had to have access to a mainframe to post these things,” Oakley says. “That selects a certain crop of people who were usually pretty intelligent.” But that didn’t guarantee civility. After all, this was still the Internet.

As the series progressed, the Itchy-sized knives came out. It was inevitable. But for Oakley, the constant critical feedback became tough to take. “Even when you have 20 compliments and one criticism,” he says, “you obsess over the criticism.” At his office, he started getting angry phone calls. Soon after that, around 1994, he disconnected his dial-up account. Oakley says he didn’t look at Internet comments again until the late ’90s, when he left the show.

The Simpsons, however, struck back at its online critics. “Radioactive Man,” penned by legendary writer John Swartzwelder, was the first episode to directly reference alt.tv.simpsons. It aired on Sept. 24, 1995, and included the slovenly Comic Book Guy monitoring newsgroups and mentioning “alt.nerd.obsessive.” If those were subtle jabs, then “The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show,” which aired on Feb. 9, 1997, was a Drederick Tatum uppercut. The plot involves show-within-a-show Itchy & Scratchy adding a new character, Poochie, in a cynical attempt to boost ratings. The episode, written by Cohen, featured this exchange:

Comic Book Guy: Last night’s Itchy & Scratchy was, without a doubt, the worst episode ever. Rest assured that I was on the Internet within minutes, registering my disgust throughout the world.

Bart: Hey, I know it wasn’t great, but what right do you have to complain?

Comic Book Guy: As a loyal viewer, I feel they owe me.

Bart: What? They’re giving you thousands of hours of entertainment for free. What could they possibly owe you? If anything, you owe them.

Comic Book Guy: Worst episode ever.

Unsurprisingly, Cohen plucked the oft-quoted “Worst episode ever” from a 1992 alt.tv.simpsons post. Its author, John R. Donald, was expressing his displeasure with the episode “Itchy and Scratchy the Movie.” To this day, Cohen does a near-perfect impression of Comic Book Guy petulantly uttering “Worst episode ever.”

Although Salon called the episode “a hilarious, slightly cruel kiss-off from the writers to the Internet fans,” Cohen now refers to it as “the ultimate homage to alt.tv.simpsons.” And at least a section of the board, it seemed, took it in that spirit. After all, who wouldn’t like being referenced on their favorite TV show? “A good episode that wouldn’t be nearly as relevant to viewers unfamiliar with the fan community,” Jonathan Haas wrote in his review.* “Grade: A, because the writers would mock me if I gave it anything else.”

As Chris Turner points out in his book Planet Simpson, the show’s wise-ass tone actively invited this kind of sarcastic commentary. Couple that with complex, detail-packed, multilayered episodes, and there was a lot for alt.tv.simpsons to dissect. The early incarnation of The Simpsons was so smart, so damn good, that its biggest fans held it to an impossibly high standard. After all, we don’t just watch the shows we like—we pore over them, judging and praising even their littlest details. But unlike, say, Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, or The Wire, The Simpsons wasn’t limited to a relatively short run. It’s not easy to sustain greatness for 500-plus episodes. “TV comedies don’t go eight, nine, 10 years,” Cohen says. “That’s the extreme outside edge of where TV comedies go. Except The Simpsons.”

As The Simpsons begins its 25th season on Sunday, the show is indisputably not as hilarious or groundbreaking as it was in its magical early years. But viewers continue to talk about it online. Alt.tv.simpsons still can be accessed through Google Groups, and a chunk of the forum’s best content is neatly curated on The Simpsons Archive. The A.V. Club also regularly reviews classic Simpsons episodes; at the bottom of those recaps, fans sometimes post old critiques from alt.tv.simpsons.

Online Simpsons fans still sum up the Internet as a whole: simultaneously angry, happy, knee-jerk, brainy, cromulent, and deranged. “There’s people who really take the show seriously and really know a lot about it,” Oakley says. “Many of their critiques are correct. That was the thing. You had to be able to sort out the valid criticism from the insane blather.”

Correction, Oct. 16, 2013: This article originally misspelled Jonathan Haas’ last name. (Return.)