In June of 1970 a displaced Minnesotan folk-singer-turned-rock-star-turned-country-crooner with a fake name and a curiously attentive fan base released a double album for Columbia Records. Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait was, in its way, as much of an end-of-the-’60s record as Abbey Road, Let It Bleed, or Led Zeppelin, with one crucial difference: Self Portrait sucked. It sucked gleefully, relentlessly, with inventiveness and purpose. Its 24 tracks included gratuitously overproduced pop and folk standards, slapdash recordings of slapdash live performances, wait-are-you-serious covers of Simon and Garfunkel and Gordon Lightfoot, and multiple instrumentals (because why else would you buy a Bob Dylan album). “What is this shit?” Greil Marcus famously wondered atop a 7,000-word pan of the album in Rolling Stone. In the wake of Woodstock, Altamont, the Manson murders, Kent State, a nation had turned its lonely eyes to Bob Dylan and received something like a middle finger for its troubles. How does it feel to be on your own?

Forty-three years removed from all this, Columbia Records has released Another Self Portrait (1969-1971): The Bootleg Series Vol. 10, and once again, it’s all a little confounding. The two-disc set—four discs if you opt for the $100 “deluxe” version—collects outtakes, alternate mixes, and other unreleased material from the Self Portrait era (the package also includes a generous helping of castaways from Self Portrait’s follow-up, New Morning). On one hand, the very existence of Another Self Portrait is a testament to Dylan’s enormous cultural stature: Even his most reviled works are deemed worthy of painstaking curation and completism (a gold-plated rerelease of Down In The Groove is surely on its way). On the other hand, asking fans to shell out substantial cash to hear discarded marginalia from an album that was, in its original form and by its maker’s own admission, mostly discarded marginalia, might once again prompt the question: What is this shit?

Another Self Portrait doesn’t answer this query, nor does it really try to. It does, however, illuminate and elaborate upon one of the strangest moments in Bob Dylan’s career, which is welcome news to all gradations of Dylanphiles (including Greil Marcus himself, who contributes an excellent essay to the set). The set isn’t an autopsy of rock music’s most infamous trolling so much as it’s a collection of contexts, and by leaving the mystery of Self Portrait unsolved the puzzle becomes all the more intriguing, more immediate, more strangely and endearingly human.

At the time of Self Portrait’s release, Bob Dylan had spent four years as music’s most famous recluse. After his much-discussed 1966 motorcycle accident, he effectively receded from public life, releasing two rather puzzling albums—the ascetically austere John Wesley Harding of 1967 and the country-soaked Nashville Skyline of 1969—and rarely appearing onstage. It was during this absence that Dylan’s celebrity swelled into something increasingly untenable, perhaps the only logical outcome when the Voice of a Generation goes silent at the very moment that generation starts hollering itself hoarse. His lyrics popped up in university classrooms and poetry anthologies, and the neologism “Dylanology” was coined; obsessive fans made pilgrimages to his house, dug through his trash, harassed his family; revolutionary groups appropriated his songs to justify various ideologies and ends. Dylan’s hiatus from the above-ground music industry also created the conditions for his music to find its way to the public in underground and unauthorized forms. Great White Wonder, released in 1969 and widely considered the first major “bootleg” in rock history, offered a trove of illicit material, including tracks recorded at Woodstock with The Band in 1967 during sessions that would soon be known as the Basement Tapes.

Self Portrait was a strike back at all of this, although in exactly what direction and to exactly what ends has never been particularly clear. Dylan, no fan of self-explication, has at times described the album as an attempt to get the world off his back, at others as a comment on the very bootlegs threatening the autonomy and integrity of his art. Still elsewhere he’s described it as simply “an expression,” and conveyed a sense of hurt that so many assumed it disingenuous. In short, it’s hard not to wonder if Dylan himself wasn’t really sure what “this shit” was, either; for all of its interest in other people’s songs and other people’s sounds, Self Portrait’s most un-Dylanesque quality was its seeming lack of conviction, a haziness of intent exemplified by the album’s notorious cover art.

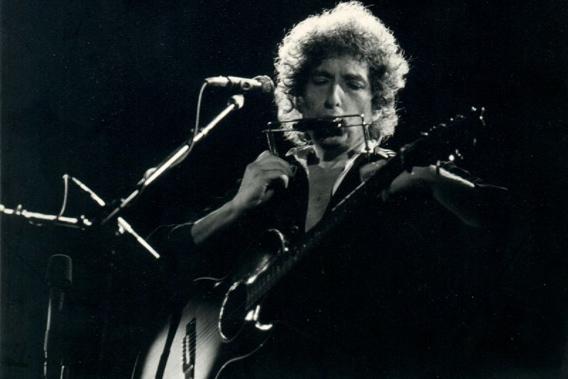

Photo by Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

Another Self Portrait helps bring this blur into focus in ways that are new, often charming, and occasionally just great. Much of the collection sets itself to stripping away intrusive overdubs and ornate production touches, the most befuddling and widely loathed aspects of the original album. “Wigwam,” one of the few original compositions on the first Self Portrait and one of its best tracks, is a delirious and oddly distant recording, Dylan’s wordless vocal washed out by a blaring horn section that seems to erupt out of some fissure in time. Another Self Portrait removes the horn overdubs, leaving Dylan’s voice alone to carry the song’s melody, and it’s suddenly a new song: warm, immediate, alive. Similar effects are achieved with “Copper Kettle” and “Belle Isle,” folk-revival chestnuts now largely unburdened of the middle-of-the-road strings and studio gadgetry that stalked the originals.

These are beautiful songs sung with seriousness and real love, and this affection is one of the great revelations of Another Self Portrait. The first Self Portrait was many things but it clearly wasn’t a joke, or at least it wasn’t just a joke. Nor was it entirely without its merits: The clattering live version of “The Mighty Quinn” with The Band sounds like someone driving a Buick 6 loaded with dynamite into the side of Big Pink, and “Alberta, No. 2,” the gently rocking version of the classic folksong that ends the album, is simply beautiful, one of the best Dylan tracks of its era. Another Self Portrait offers up a compelling case that before all the strings and sabotage there was once a pretty good record in here.

What’s more, some of the unheard material from the New Morning sessions included in the set—an album released a mere four months after Self Portrait and approvingly heralded by critics as a return to form—also dabbles in its predecessor’s grandiosity, to startlingly successful ends. A newly-unearthed mix of “New Morning” features hyperactive soul-revue horn lines and has already ruined me for the original; a lovely orchestral mix of “Sign On The Window” boasts harp and string arrangements reminiscent of early-1970s Elton John. These sorts of production choices, novel and weird as they often are, seem to be something Dylan was generally interested in, moments of experimentation by an artist whose career hardly contained anything else.

In a final and fittingly counterintuitive flourish, the absolute best track on Another Self Portrait comes at its end, and holds no connection to either Self Portrait or New Morning. This would be a previously-unheard demo of “When I Paint My Masterpiece” from early 1971, a song so good that 99 percent of the musical world couldn’t have written it in their wildest dreams. Dylan, of course, shrugged it off to The Band, who fashioned it into the high point of their 1971 album Cahoots. The infant version heard here, with its simple, gospel-inflected piano and quietly dazzling vocal, is haunting, stately and, unlike everything else on this set, entirely perfect. “Someday, everything is gonna sound like a rhapsody,” drawls Dylan, and it’s impossible not to crack a smile: After all, what kind of dull awful world gone wrong would that be.