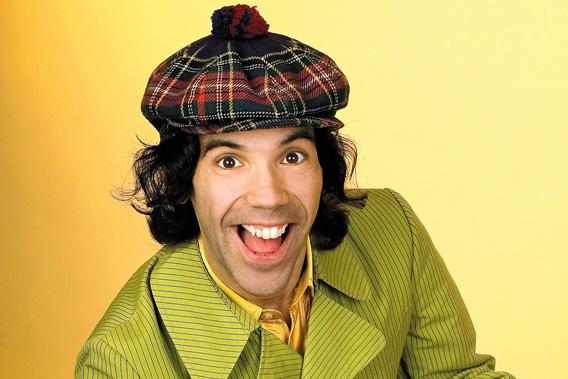

If you’re already familiar with the work of the Canadian music journalist Nardwuar the Human Serviette, please forgive me for stating the obvious: Nardwuar the Human Serviette is one of the greatest living practitioners of the art of the interview. If you’re not already familiar with his work, and you decide to check up on that claim by watching a few YouTube videos of his interviews for Vancouver public radio station CiTR-FM, he might not at first seem like all that noteworthy a figure. Or rather, he might seem noteworthy only for the most shallow and inconsequential of reasons. His style of dress, for one thing, is peculiar, occupying a sartorial no-man’s-land between first-wave punk and PGA Tour. His style of interviewing is even odder: a frenzied staccato catechism in which he bombards his interviewees with a succession of questions and prompts in the excitable, high-pitched speaking voice of the stock geek in a teen comedy. And since 1986, he’s insisted on concluding every interview by saying “Keep on rockin’ in the free world! Doot-doola-doot-doo,” to which the interviewee must reply “Doot-doo!” The whole setup, in other words, looks like a gimmick. But Nardwuar might in fact be the most revelatory interviewer of musicians in the world.

His on-screen persona is a counterintuitively attractive synthesis of—bear with me here—Ryan Seacrest, Studs Terkel, and Screech from Saved By the Bell. If that sounds nightmarish, let me assure you that the Seacrest and Screech components are largely aesthetic, and that it’s the Terkel element that runs deepest. Nardwuar is a living repository of the history and folklore of popular music; his wayward erudition is almost overwhelming, and the fieldwork he does on his subjects is often so thorough as to be unsettling. What’s most compelling about his best work—his fantastic interviews with Pharrell Williams and Waka Flocka Flame, for instance, or last month’s deeply enjoyable 46-minute conversation with Questlove—is watching the combination of wariness and fascination his apparent omniscience is met with. Nardwuar’s subjects are inevitably people who have spent a fair portion of their careers having microphones thrust into their faces—but who have never encountered an interviewer who’s done anything like this level of research into their musical backgrounds, their cultural enthusiasms, or their personal histories.

The interviews tend to be organized around the subjects’ responses to particular objects in Nardwuar’s bag of tricks. And there is, literally, a bag. His shtick—which, like all great shticks, transcends shtick—is to present people with a series of personally significant items: obscure records from local music scenes, fanzines, posters, and other cultural artifacts. When these interviews go especially well, there’s a real joy in watching the subjects’ accumulating awe at Nardwuar’s ability to get a hold of this stuff, and their perplexity at how he knows what he knows in the first place. (As with all good magicians, Nardwuar refuses to reveal the mechanics of the trick.) Impressive as it is, though, the device is effective not for what it reveals about Nardwuar’s dexterity as a researcher, but for how it tends to disarm his subjects into revealing something about themselves they would never normally reveal in an interview. It’s much less about the sleight of hand, in other words, than it is about the reaction.

Despite his hyperactivity and his impenetrably quirky persona, he knows when to keep quiet and let a reaction develop. There’s a particularly affecting moment towards the end of the long Questlove interview when Nardwuar presents him with a copy of the fanzine Roctober, featuring an article on Soul Train in its early incarnation as a Chicago variety night.* Questlove has just spent a few minutes talking about the formative influence of the show (his parents, he says, used to wake him up at 1 a.m. to watch it), and mentions that he’s currently involved in a book project on the subject. When Nardwuar hands it to him, he is rendered literally speechless; he turns his back to the camera, faces the wall, and stares down at the zine for a few wonderfully awkward seconds. “Not gonna cry,” he says. “I’m not …” It’s a lovely exchange, and a rare enough example of a celebrity and interviewer meeting on level ground. Questlove is visibly affected and excited by Nardwuar’s gifts as an archivist and researcher. “I truly believe you could have found Bin Laden,” he says, clearly only half joking.

One of the most interesting things about watching a lot of Nardwuar’s interviews (and if you watch one, chances are you’ll end up watching a lot) is the way that they tend to reveal aspects of artists’ personalities that we’re not accustomed to seeing. His aggressive uncoolness—the silly hat, the grating manner, the relentlessly pursued obsession with minutiae—amounts to a kind of challenge. The respect he gets from people like Big K.R.I.T., Grimes, Brother Ali, Pharrell, Snoop Dogg, Joanna Newsom, El-P, Questlove, and Ian MacKaye reflects the extent to which these people are, in their different ways, smart and empathic enough to see past the geeky, gimmicky surface to the value of what he’s doing.

But that uncoolness brings out a lack of basic decency—a shabbiness and stupidity—in others. A 1991 interview with Sonic Youth, for instance, was especially difficult for me, a Sonic Youth fan, to watch—first for how it reveals their stunted and clichéd conception of what it means to be a bunch of cool people in a cool rock band, and then for how it reveals them as just standard-issue schoolyard bullies. Lee Ranaldo breaks a rare 7-inch record Nardwuar has brought them, and then he and Thurston Moore (then age 33 and 35 respectively) grab him and pull his T-shirt over his head as he struggles and shouts. “You idiot!” he screams at Ranaldo. “You fucking piece of shit!” It’s a grim spectacle, but worth sitting through as a reminder of how shallow and transparently fraudulent the performance of countercultural cool can often be.

There’s also a horrible 2003 interview with Blur, in which drummer Dave Rowntree intimidates and threatens Nardwuar, stealing his hat and glasses, physically pushing him around while the other band members titter in the background. (Rowntree publicly apologized for this eight years later, around the time he also just happened to be embarking on a political career. He blamed it squarely on a coke habit, rather than any deeper flaws in his personality.)

Nardwuar was born John Ruskin in Vancouver in 1968—presumably no relation to the Victorian art critic of the same name. (The story behind the name Nardwuar the Human Serviette is both highly idiosyncratic and disappointingly banal: “Nardwuar” was just a word he made up that he thought sounded neat; “Human” comes from the song “Human Fly” by the Cramps; and as an eccentric emblem of his Canadianness he tacked on “Serviette,” because it’s a word rarely used in the napkin-centric United States.) His mother, Olga Ruskin, was a journalist, Vancouver local historian, and public access TV show host. Through her connections, he got a job at a community TV station in 1986, around which time he started promoting punk shows in Vancouver and fronting an exuberantly goofy garage band called the Evaporators. (The band is still a going concern: Nardwuar is nothing if not tenacious).

The following year, he began presenting a show on CiTR-FM, where he started interviewing local punk bands and bigger touring acts. In 1992 he started putting together video clips for a show on local cable TV, and selling VHS compilations via mail order, which built a small cult following. At the insane height of Nirvana’s fame, a few months before Kurt Cobain’s death, Nardwuar managed to inveigle his way into an interview with the band. He kept plugging away throughout the decade, gradually becoming a sort of alternative national treasure until, in 2001, he finally got his own spot on the Canadian music television channel MuchMusic, which led to higher-profile interviews and a nationwide audience. It was YouTube, though, that really brought his oeuvre, in all its vastness and strangeness, to a large and appreciative audience worldwide.

When I first watched the videos, I wondered: Is Nardwuar—how to put this—for real? In all the years Nardwuar has been doing what he does, he has never given the impression of its involving any sort of persona or performance. Even in those moments when things go horribly wrong (the Sonic Youth and Blur interviews, for instance) he never comes close to breaking character; Nardwuar in distress is clearly the same person as Nardwuar enjoying himself. And this is because—despite the ridiculous name, the squeaky voice and the outlandish getup—he’s actually no more a “character” than, say, Jon Stewart or Piers Morgan, and probably a good deal less. As the Canadian journalist Dave Watson put it, “There is a difference between the guy when he’s on-air and when he’s not, but it’s not a night-and-day difference. More like a 1 pm/3 pm thing. He definitely emphasizes some aspects of himself when the spotlight’s on, but it’s still the same guy. Essentially, he’s just letting himself go wild, in a way only children usually get to do.”

So it’s not so much that there’s a method to Nardwuar’s madness, as that there’s a madness to his method. The whole gonzo production—from the exhaustive pursuit of trivia to the frequently anxious insistence on ending each interview with the “Doot-doola-doot-doo” exchange—does seem like a kind of creatively sublimated obsessive compulsion. And so he’s clearly a peculiar person, but his peculiarities are channeled into his work in a way that’s extraordinarily effective.

Nardwuar may be an eccentric product of punk culture—Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra has been a longstanding inspiration, and his Alternative Tentacles label has released DVDs of his interviews and an album by the Evaporators—but it’s the rap world that has embraced him most warmly, and provided him with his broadest audience. In 2008, Pharrell Williams was so awed by his unique interviewing skills, and by his encyclopedic knowledge of music and pop culture, that he harangued Jay-Z with phone calls until he agreed to meet with Nardwuar. (The result was actually a little anticlimactic; his relentlessly unnuanced approach to interviewing leaves him unsuited to drawing out more aloof types like Jay-Z.)

Since then, Pharrell has become a sort of patron figure, connecting him with major hip-hop players and signing him up to do a weekly interview series on his YouTube channel. There was a gratifying moment for dedicated Nardwuarians at SXSW a couple of months back, when Pharrell hijacked their second filmed conversation and turned it into a Nardwuar-style meta-interview of the interviewer, complete with props and fanatical fact-finding. Like most of the best Nardwuar moments, its animating force was a childishly exuberant, geeky delight in the pursuit of pop-culture minutiae—something that Pharrell, for all his hip sophistication, clearly shares. It was a funny and touching tribute to a completely unique figure, and a recognition of Nardwuar’s two most effective journalistic tools: deep research and pure joy.

Correction, July 8, 2013: This article originally misspelled the name of the fanzine Nardwuar presented to Questlove. It’s spelled Roctober, not Rocktober. (Return to the corrected sentence.)