This article is adapted from a post on Larry Cebula’s blog, Northwest History.

In a popular recent academic blog post, the author, a historian, bemoans an imagined decline of diary-keeping in the present era. Future historians will have nothing to write about! The author urges us to sharpen our quill pens, pull out a piece of vellum and begin journaling. “This is your duty,” he proclaims. “Create that thing that historians crave—real, firsthand accounts.”

But this is silly, for a number of reasons. To start with, the author is using a blog on the Internet to complain that no one is writing about their lives anymore. The truth is precisely the opposite—we are living through an explosion of personal writing and documentation that is unprecedented in human history. More than a billion people are on Facebook, posting about their days, complete with pictures. Half a billion are on Twitter. There are tens of millions of blogs. And let’s throw Instagram, YouTube, and similar services into the mix. And of course there is email—which is indeed being saved, as recent news revelations about the NSA should reassure all of us.

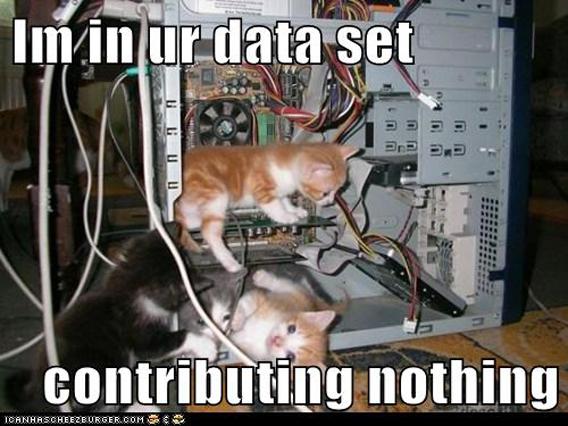

Cats, in particular, are being documented to an amazing extent.

Well, you might argue, there’s a big difference between Aunt Edna’s Facebook updates (“Doubled the prune juice this morning–will let you all know how it works!”) and Mary Chesnut’s diary. It’s worth noting how extremely atypical are the handful of historian’s’ favorite diaries. As every working historian has come to realize, for every Mary Chesnut or George Templeton Strong, there are a hundred surviving diaries of stoic Norwegian farmers or busy millworkers are that are considerably less than illuminating:

Noviember 2, 1863: rained.

Novermber 3, 1863: Raind

Nobember 5, 1863: Cow dyed.

Novebmer 8, 1863: Did’nt rain

In contrast, future historians of my era (for whom this post is written) will have information, both useful and useless, sprayed at them with a fire hose. It’s worth thinking about how you future historians can sift through the flood of primary-source material to sort the 21st-century Mary Chesnuts from the Aunt Ednas.

Imagine if Thomas Jefferson had a Facebook page, commented on the pages of his Facebook friends, tweeted (“Tip to fellow planters: Increase farm income w/ a nail factory manned by young slaves! #slavery #childlabor #Monticello”), and posted photos to Instagram (“Used the sepia filter for this pic of Sally on a bearskin rug. #naughty”). Now imagine that all of his contemporaries were Facebooking and tweeting about Jefferson, Instagramming Monticello, and posting their comments on the Declaration of Independence’s second draft on Google Docs! We would have vastly more information about the man. And Lord knows there is no shortage of primary-source information about Jefferson as is.

The real revolution in personal writing and documentation for our era, however, is the way that it will illuminate the lives of us peasants. Every fry cook at McDonald’s has a Facebook page. And as I hinted above, it is not just that people are writing more than ever before. Future historians will have hundreds of millions of images (from Instagram alone) of people’s daily lives. Add tens of millions of videos. And then there is the metadata—GPS locations for those posts and images, networks of friends and sharing, tags and hashtags! For broader context, you 22nd-century historians will pull up an archived Google Street View of the neighborhood, see what cable services the subject subscribed to, and peruse old Amazon order histories and wish lists.

Not so fast, my contemporary readers might point out. Most of these sources are commercial services, with privacy policies and limited sharing. How many of these records will even exist in 100 years? Anyway, it isn’t like you can just pull up the Facebook pages of all Cleveland fry cooks and sort by the text “salmonella.”

Not yet, you can’t, but you will be able to. My 22nd-century readers will of course be aware of the Steve Jobs Personal Privacy Elimination Act of 2037, but even readers of my own era should know about the rapid erosion of privacy. Even before the phenomena became apparent, there was a general principle known as the “75-year rule” that most government documents became public after that amount of time. And as for the saving of old Facebook posts and the like, data is money, and data is security, and storage costs continue to fall like a stone.

Digital preservation has made great strides in the decades since NASA lost the original moon landing tapes. Today digital archivists use such preservation strategies as redundancy (keeping multiple copies of files in different places) and forward migration (moving files into the latest format so you can still read them). At the Washington State Archives, Digital Archives (where I work), 117 million digital objects are preserved in multiple backups, both on hard drives and on magnetic tapes. Yet our data is a fraction of what is being captured and preserved by Google, Yahoo, and other tech giants. And the nonprofit Internet Archive has preserved more than 10 petabytes of digital data, from expired Geocities pages to the Web’s largest collection of bootleg Grateful Dead recordings.

Not all or even most of the current flood of stuff will survive into the next century, but lots and lots of it will. Far from the “digital dark age” that some were predicting only 10 years ago, the future will be awash in data from our era. Our LOLCats are safe for eternity.

So to all those future historians who stumble across this blog post long after I am dead: Sorry for all the stuff. I know you people are going to have unimaginable tools for sorting, thinning, combining and analyze the mountain of “real, firsthand accounts” that my generation has been thoughtlessly creating. Still, I know that on some days you must grow weary of examining the 746,000 variations on a single meme. You must sometimes shout: “Stupid dead person, when your hard drive gets full don’t just buy a bigger backup, sort your damn files!” You must spend days reading the Facebook feed of some 13-year-old who later became famous, and you must feel despair.

Sorry about that, historians of the 22nd century. I am sorry that I made so many blog posts featuring someone else’s YouTube video. Sorry that so many of my Facebook updates are vacuous. Sorry that my tweets bring down the tenor of the entire medium. Sorry about all of my files undescriptively labeled DSCimage987234534.jpg and GrantProposal2,docx. Sorry for the mess.

I did make you a present, though:

Image courtesy icanhascheezburger.com