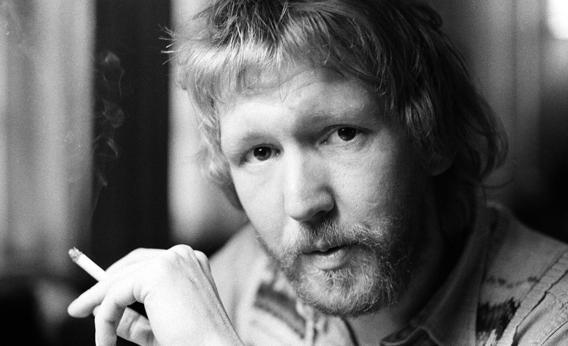

If Lennon-McCartney was the question, the answer was: this guy. What happens, in other words, if you combine in one person, in one talent, in a single opus, the whimsical facility of Paul and the howlingness and perversity of John? On June 5, 1941, Mother Nature—in antic mood—gave it a shot; prodigious chaos ensued. And the name of the chaos was Harry Nilsson.

You may know him from his cover versions: his dreamy, string-borne version of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’ At Me” (used by John Schlesinger in Midnight Cowboy) or the harrowing super-schmaltz of “Without You”—I can’t liiiiiiiiiiive … etc.—which he borrowed from Badfinger in 1971 and which went on to become (characteristically, topsy-turvily for this most prolific composer) his biggest hit. “Without You” is sort of a nightmare, the ’70s at their maudlin and woolly-faced worst, but there’s no question that Nilsson’s vocal performance transports the song to a garish emotional summit. Can’t LIIIIIVE! “Harry burst into terrifically unpleasant hemorrhoids on that top note,” Derek Taylor, one-time Beatles press officer, reports in Alyn Shipton’s new Nilsson: The Life of a Singer-Songwriter. “Whenever I hear it I always think of the hemorrhoids.”

These ass-flavored memories are somewhat atypical of Shipton’s book, which is, by and large, a measured and scholarly tread through the Nilsson oeuvre, with considerable attention paid to demos, arrangements, recording techniques, changes of key, and so on. Shipton is appropriately in tune with Nilsson the studio craftsman, the sonic fiddler-diddler multitracking himself into infinity, but Nilsson the man, the flesh-and-blood nutcase, rather evades him. We read about young Harry holding up a liquor store with the old finger-in-the-coat-pocket fake gun trick in 1958 (he needed $60 to pay off one of his mother’s bad checks), and we read about him getting into it with 12 London taxi drivers in 1985. (Nilsson and his friend took a bit of a beating; the drivers collectively suffered one broken jaw and one heart attack.) We read about the nights of heroic dissipation in L.A. with John Lennon, and the strength-giving injection of sheep placenta cells into the Nilsson buttocks at the Clinique de Prairie in Montreux. (As Shipton comments: “Subsequent medical research has shown that [these treatments] were scientifically suspect at best. …”) But Shipton writes of such things with a certain headmasterly regret, and seems happier turning his perfectionist’s ear to the musical minutiae. “One or two of the backing harmonies might have benefited from a retake,” he sniffs during a technical appraisal of “The Lottery Song,” “as there are moments when Nilsson’s usually faultless pitch wavered slightly.”

Then again, you’d have to be some sort of biographical Cubist to capture all the simultaneities and overlapping planes of Nilsson. How to frame the mind behind the schizoid glory that is 1971’s Nilsson Schmilsson, an album that cycles through merrily alienated folk-rock (“Driving Along”) and gently pulsing Barbadian hangover (“Early in the Morning”), before descending into the livid, dragon-bones funk of “Jump Into The Fire”? (Remember Ray Liotta scanning the sky for police choppers in Goodfellas, driving around pop-eyed with a paper bag full of handguns? Remember the song that’s whooping and reeling in the background? “You can shake me uh-uh-up … Or I can bring you doooown.” That’s “Jump Into the Fire.”) Some of his songs are infused with a manic gaiety, some are haggard with sorrow, and quite a few seem to have no meaning at all—as if they’ve simply spun themselves, grinning, out of the ether of his abilities. (This is his Paul McCartney side.)

Which is the essentially expressive Nilsson number? Is it him roaring his way red-tonsilled through “Many Rivers to Cross,” on the Lennon-produced Pussy Cats? Or is it the miniature nonhuman scene of “The Moonbeam Song,” in which a night breeze and a layer of moonlight chase each other through rhyming loop-de-loops—the rain, the train, the windowpane and the weathervane—while choirs of sighing Beach Boys float off in ecstasy? Is it the Plastic Ono Band thump and build of “Ambush,” or the McCartneyesque bounce of “Gotta Get Up”? Nilsson sang a lot of songs about being down, done, deep-sea depressed: “Down to the bottom/ Hello, is there anybody else here? (“Lifeline”), Down to the bottom, to the bottom of a hole (“Down”), Goin’ down/ Deeper than the deepest ocean” (“Goin’ Down.”) But then there’s “Think About Your Troubles,” a piano-bar invitation to imagine your own salty tears poured into the sea and drunk by helpful fishes, which are then consumed by a whale, whose eventual death and decomposition releases your tears again, into the consoling element of universal saltiness … Also, the melancholy sentiments of “Goin’ Down” are somewhat offset by the fact that he spends half the song yodelling.

Shipton’s biography, and the release this summer of a 17-disc box set that comprises Nilsson’s entire recorded output for RCA, 1967–77, can be seen as part of a larger movement to retrieve or reconstruct the reputation of this wayward American songwriter. And while it’s certainly nice to have the information organized, and all the songs gathered together, the attempt at rehabilitation turns me off a little. The sneaky term “self-sabotage,” hallmark of the psychological philistine, is often used in connection with Nilsson. For his wacky decisions, and the permanent rampage that was his lifestyle, he has incurred the wagging finger of posterity. If you watch John Scheinfeld’s 2006 documentary Who Is Harry Nilsson and Why Is Everyone Talking About Him?, you’ll hear that he changed, went dark, stopped taking advice, had a death wish; that he wrecked his lissome, three-and-a-half-octave-range voice with booze and cigarettes and Lennonoid primal-screaming. Shame! But we should remember here the profound words of Nicholson Baker in The Mezzanine: “You corrode the chromium, giggly, crossword puzzle-solving parts of your mind with pain and poison”—he’s talking about alcohol— “forcing the neurons to take responsibility for themselves and those around them … The scarred places left behind have unusual surfaces, roughnesses enough to become the nodes around which wisdom weaves its fibrils.” In the musical being of Harry Nilsson there were many chromium, giggly, crossword-solving parts. Did his Muse demand a rock ’n’ roll assault upon these parts, to expose the pain and wildness beneath? Too fanciful a notion, probably. Let’s just say that he did what he had to do. All we have to do is listen.