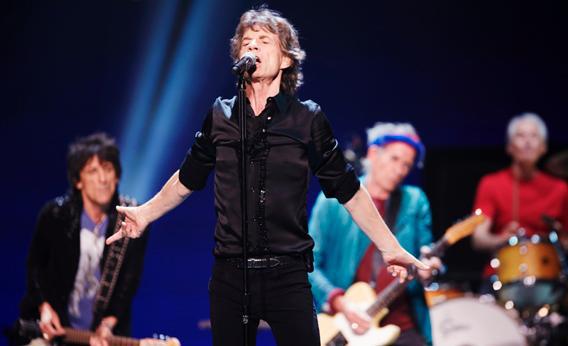

The Rolling Stones are in the midst of celebrating 50 years as a rock-and-roll band, a golden anniversary that’s occasioned a tour, countless merchandising opportunities, and some pesky ontological questions as to what actually constitutes 50 years as a rock-and-roll band. In the first 25 years of the Rolling Stones’ existence, they released 21 albums’ worth of original material; in the second 25, they’ve released four. The Stones have mostly spent this half of their careers as a lucrative self-tribute act, masters of the deluxe re-master, salesmen of their own history. Earlier this year the band released a boxed set of a long-circulating bootleg of a 1973 live show, replete with photo book, souvenir wristwatch, and an asking price of $750. That’s a steep surcharge for a concert that happened 40 years ago.

It’s all rather charmingly distasteful, and to love the Rolling Stones has always been to love them slightly in spite of themselves. And yet there’s one piece of the band’s history that remains untouched, unmarketed, un-reissued-with-limited-edition-pair-of-dog-overalls. This would be the 1972 tour documentary Cocksucker Blues, the most famous rock-and-roll movie that barely anyone has ever seen, the lost chord of the World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band. It’s a film that deserves to be watched, and heard, by anyone who thinks they love the Rolling Stones and anyone who thinks they don’t, and the greatest gift the band could give to This Our Year of Stonesian Extravaganza is to finally release the damn thing.

The tale of Cocksucker Blues is as sordid as its title. In 1972 the Rolling Stones hired photographer Robert Frank to make a movie of their upcoming American tour. Frank was already well-known for his 1958 book The Americans, a photographic tapestry of lonely Americana. The Stones were fans, and had displayed images from the work on the cover of their latest album, Exile on Main St. The tour, which boasted 22-year-old Stevie Wonder as an opening act, promised to be the most memorable (and profitable) in history. The band hoped Frank’s movie would cloak them in deserved glory and ease the considerable controversy roused by their previous film, Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin’s Gimme Shelter, which had notoriously captured the murder of teenager Meredith Hunter at Altamont Speedway as the Stones played “Under My Thumb.”

As someone once said, you can’t always get what you want. The film that Frank delivered was a ragged travelogue of debauchery and despair, a work that pulled back the curtain on the Stones’ sex-drugs-and-rock-‘n’-roll image to reveal a gaping wound. The Rolling Stones took one look at the movie and blocked its release, for fear that it would cause them to be barred from returning to the United States. In 1977, Frank went to court and won the right to exhibit Cocksucker Blues four times a year, on the condition that the filmmaker himself was present; in years since, bootlegs have circulated among fans.

Due to these various circumstances, hardly anyone has ever seen Cocksucker Blues without having already been steeped in its legends, or its myths—before my first viewing I’d caught wind of a scene involving groupies and Mars bars and, well, use your imagination, because it doesn’t exist. Anyone coming to the film expecting 90 minutes of pornographic bacchanalia will be sorely disappointed; anyone expecting 90 minutes of dope-soaked apocalypse will be slightly less disappointed but should still head elsewhere, probably to a therapist.

But it ought to be seen, because Cocksucker Blues is a hell of a film, in every sense of the phrase. It shares in the verité trappings of Gimme Shelter, but if the Maysles’ preferred aesthetic was “direct cinema,” Frank’s is more like indirect cinema: impressionistic, collagist, morally and emotionally destabilizing. There is a great deal in the film to dislike, starting with pretty much every person who appears on-screen. The Stones come off as aloof and narcotically disoriented, the celebrities surrounding them—Truman Capote, Andy Warhol, Lee Radziwill—as dull and preening.

Most troubling of all are the unfamous players, the roadies and groupies and hangers-on who seem plucked from the pages of Slouching Towards Bethlehem and are now lost to history, or to worse. We meet a fan bemoaning the injustice that her LSD usage has caused her young daughter to be taken into protective custody; after all, mom protests, “she was born on acid!” We see a man and woman shooting heroin, filmed with bored detachment, the only sound the whir of a hand-held camera. Upon completion the woman looks up and asks, unnervingly and entirely validly, “Why did you want to film that?”

The film’s most disturbing scene, and the one that most lives down to its reputation, takes place on the Stones’ touring plane. We see explicit and zipless sex. We see clothed roadies wrestling with naked women in a manner that seems dubiously consensual, as band members play tambourines and maracas in leering encouragement. At one point Keith Richards emphatically gestures at Frank to stop filming; he doesn’t. By the time the scene finally ends we feel drained, nauseated, ashamed of ourselves and everyone else in this world.

These are emotions not typically associated with rock films, and if only for this reason Cocksucker Blues is an important work. But it’s also a riveting portrayal of beauty in decay, and Cocksucker Blues’ most redemptive moments come in its musical performances. Frank has no use for the sumptuous stage sequences of later concert films like Scorsese’s The Last Waltz or Demme’s Stop Making Sense; the performance footage in Cocksucker Blues is frenetic, explosive, and almost random in composition. “Brown Sugar” is captured by a hand-held camera so hyperactive it seems to mimic Jagger’s dance moves; “All Down the Line” is shot almost entirely from behind the drum kit, Charlie Watts’ splashing hi-hat in the foreground, hypnotically obscuring, then becoming, the main event. In a particularly stunning scene Stevie Wonder joins the band onstage for a medley of “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” as the camera scrambles about, bottling a moment more intoxicating than every substance backstage combined.

It’s perhaps fitting that the film’s best sequence begins in a hotel room, where Mick and Keith are hanging out and the latter puts on a hot-off-the-presses acetate of the Stones’ latest single, “Happy.” The pair sit on the bed, smoking cigarettes, listening intently as one of the best rockand-roll songs ever recorded wafts from their stereo. Then, at the top of the song’s first chorus, Frank suddenly cuts to the Stones performing the song live onstage in front of thousands, gods in the flesh. Finally, toward the song’s end, Frank cuts back to the hotel room, where Mick and Keith are lost in listening, singing along, young men in love with their art, their jobs, and in some still-meaningful way, each other. The record fades and stops; Keith looks up, and complains about the mix.

Cocksucker Blues is raw, disturbed, equal parts quotidian and sublime, a completely honest depiction of a band on the road and a harrowing document of artistic triumph crashing into personal hell. It’s well worth the price of admission, and the opportunity to pay that price might finally be coming: Late last year, MOMA showed Frank’s film as part of a retrospective in honor of the Stones, with the band’s blessing. Cocksucker Blues isn’t for the faint of heart, and that’s just fine; the faint of heart don’t listen to Exile on Main St. Fifty years on, the Stones grow old, but this was once a band with teeth in its mouth and blood on its hands, and no moss in sight.