Are We Good?

Comedian Marc Maron’s unlikely career is at a crossroads.

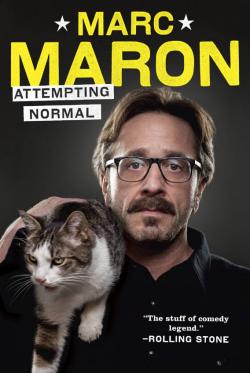

Courtesy of Leigh Righton

When he was 35, Marc Maron was unhappily married and had a serious problem with drugs and alcohol. Then he met a beautiful aspiring comic who said she was a fan and that she could help him get sober. He fell hard for this 23-year-old, and they began an affair. But he couldn’t decide what to do about it. He called his friend Sam, “a bitter but brilliant writer, who was married and had just had a kid.” Sam told him to “be responsible,” that he had made a commitment and should “try to honor it,” that this infatuation would pass. So Maron called another friend, a comic named Dave, who told him to go for it. He did. Eventually, Maron divorced his first wife and married the younger woman. A few years later, he and the younger woman got divorced, too.

Maron tells that story in his new memoir, Attempting Normal. Though he doesn’t spell it out completely, the bitter but brilliant writer friend is probably Sam Lipsyte, with whom Maron goes way back. (Who’s “Dave”? Your guess is as good as mine.) I picked up Attempting Normal shortly after reading Lipsyte’s latest book of acidly funny short stories, and when the latter author popped up in the former volume, it hit me: Prior to starting his podcast, WTF, Marc Maron resembled no one so much as he did a Sam Lipsyte character. Like many Lipsyte protagonists, he was a middle-aged guy with artistic aspirations who, despite some notable successes, considered himself, on some level, a failure. He held the record for most guest spots on Late Night with Conan O’Brien, which is something like being the all-time minor league home run leader. He was bitter and resentful, twice divorced, recently fired, and had taken in several stray cats. Then he began sneaking into his old workplace to record his angry thoughts and beam them out via the Internet to a possibly indifferent universe.

If Marc Maron really was a character in a Sam Lipsyte book, that’s where his story would have ended, his after-hours rants about mom and dad and Lorne Michaels disappearing into the void. But they didn’t disappear; people started listening. And these transmissions weren’t just rants: Though the format of WTF varied a bit in the early days, it always revolved around a long interview segment. It is the chief irony of Maron’s rather unlikely career that a comic who is, even for a comic, particularly self-involved—by his own description as well as seemingly everyone else’s—got his big break by asking other people about their lives.

Maron’s degree of self-involvement is part of what makes WTF so good. Ira Glass, a one-time guest on the podcast who knows something about getting other people to talk about themselves into microphones, has said that Maron is “emotionally present and he makes you emotionally present.” But it’s more than that. When Maron interviews someone for WTF, he is generally trying to understand not only the person he’s talking to but also himself. Especially in the early episodes, he was often trying to figure out why his guests, nearly always other comics, had succeeded in ways that he had not. Some of Maron’s stock questions, even ones that sound like standard interview boilerplate, feed this abiding interest. “What’d your old man do?” he asks nearly everyone who comes by his garage, where most episodes are now taped. A basic biographical question, but also a way of getting at what kind of leg up a guest did or didn’t have. “Who were your guys?” he always wonders. It’s a version of the old chestnut, “Who are your influences?” But when Maron asks the question, it partly means, “Did you have better idols than I did?”

When your work life is not going well—especially if you’re professionally ambitious and even more so if your chosen field is the sort that has an audience—it is easy to isolate yourself, to shy away from friends and from peers and avoid acknowledging that things are not going as you hoped they would. Much of the power of WTF comes from Maron doing the exact opposite of that. He said to the world, “My life is a disaster right now. Help me understand what the fuck is going on.” (I’m paraphrasing.) It is maybe not a coincidence that his podcast became a phenomenon at a time when many Americans were losing their jobs. It is definitely not a coincidence that the best and most celebrated episode of WTF involves Maron coming to terms with the remarkable success of an old friend whose professional triumphs inspired a jealousy in Maron that nearly ruined the friendship. It helped, of course, that the old friend was Louis C.K.

But what story do you tell when the universe answers back? When these conversations not only yield some understanding but also the kind of success that had eluded you for years? Maron is now figuring out how to answer that question, to judge from his new book, his fictional-but-totally-autobiographical TV series Maron (Fridays at 10 on IFC), and his next stand-up special, which he taped a couple weeks ago in New York. Of the three, my favorite is the series, called Maron, which appears to have a real shot at capturing the one-in-a-million emotional trajectory Maron’s actual life has followed since the podcast started flourishing. The three episodes I’ve seen draw from the moment that WTF was just getting off the ground, and consist largely of Maron’s humbling by peers, family, and life in general. Maron is the beleaguered straight man; his guest stars—especially Dave Foley and Andy Kindler, both hilarious as themselves—get the best lines. The episodes are punctuated with scenes of Maron monologuing into the garage microphone, Carrie Bradshaw or Doogie Howser-like, which may sound bad; the effect is not subtle. But it captures the earnest, A.A.-inflected, self-help aspect of Maron’s comedy and podcast work, which is an essential part of his appeal.

For that reason, I had thought a book might be the right format for Maron’s narrative. (In the memoir’s intro, Maron says, “Every book is a self-help book to me.”) But while Maron’s observations are unsurprisingly precise, the thing as a whole is a bit scattershot. Chapters about Maron’s past, like the one about the end of his first marriage—or another, the high point of the book, about two darkly funny and crushingly sad encounters with prostitutes—have a satisfying heaviness to them that gets lost later on, as though Maron hasn’t quite got a handle on the story of the last few years of his life. As funny as his bits about such crucial topics as expensive jeans and Whole Foods and really spicy chicken may be, I wonder: What are the signposts? What’s the direction? I imagine Maron wonders too.

As for that stand-up special, Maron taped it on April 15 at Le Poisson Rouge, a smallish venue in Greenwich Village. Several hours earlier, two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon. Waiting for him to come onstage, I talked with a fellow fan about whether Maron would bring up what happened. Maron went to college at B.U. and, after a short stint in L.A., got his comedy career going in Boston. We agreed he’d probably bring it up. He didn’t.

On WTF a few days later, he explained that decision partly by telling a story. Nearly two decades ago, Louis C.K. was scheduled to tape his first appearance on the Late Show With David Letterman the same day that more than 150 people were killed in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Walking down a street in New York that day, C.K. asked Maron if he should say something about it in his Letterman set. Maron said of course he should, that it would be crazy not to. C.K. told a Late Show producer what Maron had told him. The producer replied, “Well, that’s why Maron’s not doing the show.” C.K. didn’t mention the bombing.

There was a time when Maron might have told that story to illustrate the corporate fear of truth-telling and how rebel comics like himself are kept out of the big-time by greedy gatekeepers pandering to a cowardly audience. Or something. Now it had a more complicated meaning, one Maron was still trying to find. “It was weird,” he said of not bringing up Boston that night. “It was an emotional decision for me.” To be perfectly honest, I wish Maron had talked about Boston that night—but I’m from there, and that’s probably a little selfish of me. He’d been building up to that set for a while, and it’s supposed to air several weeks down the road, when the story won’t be on everyone’s minds (and will have changed considerably). And that rebel ethos, which once would have pushed Maron to talk about it anyway? It has its limitations—chief among them, perhaps, a dubious romanticism.

Success may have its limitations, too. But a quarter-century after his comedy career began, Marc Maron isn’t in the minors anymore. He built his own field, and people came. (The comic Nate Bargatze says being on WTF did more for his career than being on Conan.) Now he has to decide just what game he’s going to play.