Tom Cruise is one of the world’s most visible people, and one of its least seen. Movie stars, like politicians or other public figures, learn early on how to feign candor while keeping themselves hidden, revealing enough to give their adoring public a feeling of personal connection while keeping their private selves private. But in the course of more than three decades in the public eye, Cruise has lost the art of authenticity. Queue up the talk show appearances promoting his new movie, Oblivion, on YouTube, and you’ll see an endless procession of gigawatt grins, gleaming teeth stretching from Burbank to Manhattan. What you won’t see is a single genuine or unstudied moment, a glimpse of the man sealed inside that inch-thick coating of industrial-grade charisma. Compare any of those interviews with a 25-year-old clip of Cruise on Oprah (long before his infamous couch dance), where he seems visibly nervous and a little bit lost—in a word, human. Watch enough of Cruise, and you start to wonder if there’s anyone in there at all.

This is a question that, to judge from his recent movies, Cruise has begun to ask himself as well. Oblivion begins in the mode of War of the Worlds or Minority Report, with Cruise’s Jack a dystopian warrior battling the forces of chaos. Humanity, we’re told, nearly perished in a war with an alien race they call the Scavs, and survived only by nuking their own planet, rendering most of its surface uninhabitable. What remains of the species has resettled on one of Saturn’s moons, leaving behind a skeleton crew to tap the Earth’s few remaining resources. But this movie does not continue in that vein. Spoilers follow.

In the course of the film, we learn this is a lie, a fiction promulgated by an alien intelligence whose triangular vessel, known as The Tet, hovers in Earth’s sky like a replacement for its demolished moon. Jack and his partner, Vica (Andrea Riseborough), believe that they’re taking orders from a human being (a drawling Melissa Leo), and that their memories have been wiped to help them focus on their mission. But in fact they are clones, one of dozens of identical pairs scattered around the globe, each carefully restricted to a designated sector. Still, memories of their original selves, especially of Jack’s wife, Julia (Olga Kurylenko), linger, and as Jack discovers more of the truth, they worm their way to the surface—a process that also takes root in the fellow Jack clone he meets along the way.

Most of Oblivion’s reviews praised the movie’s white-on-white design while dismissing it as an empty-headed trifle, but there are deeply strange ideas lurking under its surface, ideas the movie itself barely glances at. Start with the notion of memory as a physical quantity: not an accumulation of life experiences or a pattern of electrical impulses but something that can be cloned with the rest of the body. Going further down that road, Oblivion’s finale asks the audience to ignore the differences between clones and seamlessly substitute one for the other. The primary Jack is (presumably) long dead, and the Jack we’ve been following for most of the movie gives his life to destroy The Tet, but another shows up in his place, to live out the life with Julia that his original self was denied.

The name of Oblivion’s world-plundering alien conjures the specter of the Vietnam War, as does its vision of human salvation through self-immolation. (It became necessary to destroy the planet in order to save it.) But it also resonates profoundly, if imprecisely, with the teachings of the Church of Scientology, for which Cruise is the world’s most public advocate. (The spectacle of Cruise’s character being placed in pseudo-domestic bliss uncannily recalls the stories about prospective wives being auditioned in Scientology’s chambers.) Although Scientologists are notoriously secretive about their beliefs—even Lawrence Wright’s meticulously reported book, Going Clear, had to rely in part on WikiLeaks documents—numerous accounts hold that the church’s confidential scriptures attribute humanity’s woes to a galactic dictator named Xenu, who annihilated his empire’s excess population with hydrogen bombs and left their disembodied souls, called thetans, behind. Scientologists deny any belief in reincarnation, but they reportedly believe that those thetans inhabit human bodies, moving between them when one dies. A memory of a thetan’s previous existence does not survive the transition, but the scars of its past life, called engrams, remain.

The parallels between Scientologist dogma and Oblivion’s plot are not exact, but it’s not hard to see how a person drawn to the one could be drawn to the other. Religions, like movies, are based in narratives, and they similarly seek to give structure to the inchoate stuff of life. And, in many ways, Oblivion is simply the most concrete example of a theme that stretches back through Cruise’s entire filmography, in which knowing oneself and being known by others is not only profoundly difficult, but also frequently dangerous.

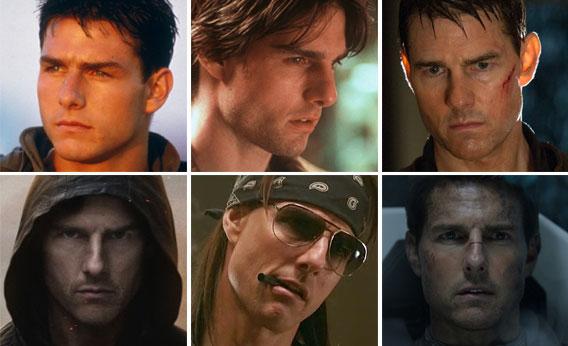

Cruise may not be a director, but a star of his magnitude leaves a profound mark on the projects he chooses, especially since his involvement alone is enough to guarantee their existence. There are superficial continuities, like a preference for wire-rimmed sunglasses, battered leather jackets, and fast, loud vehicles. (One imagines the following note relayed during Oblivion’s development: “Tom loves the script, but he feels that his character would ride a motorcycle.”) And there are deeper currents, psychic riptides, born of the collision between the way Cruise chooses to present himself and the way, so far as we can tell, he really is.

If there’s a thread that runs through Cruise’s recent movies, it’s this: You may think you know me, but you don’t. His character in the Mission: Impossible movies seamlessly switches faces and is described as “a ghost”; even Ethan Hunt’s surname reflects his elusive nature. In Knight and Day, he’s a high-level spook who’s built an untraceable life on a private island. And in last year’s Jack Reacher, he’s a man without a country, an American citizen who’s barely set foot on the nation’s soil: “blood military,” he’s called. Jack Reacher has “no driver’s license, current or expired, no residence, current or former, no credit cards, no credit history, no P.O. Box, cell phone, email.” By the standards of his home country, he doesn’t exist.

Jack is a soldier, but one who’s never had a chance to see what he’s been fighting for. Once he gets a glimpse, he doesn’t think much of it. In an extraordinary scene, he gazes out an office window at a neighboring building, literally and figuratively looking down on the blue-lit workers slaving away at their desks. “Imagine you’ve spent your whole life in other parts of the world, being told you’re defending freedom,” he says to Rosamund Pike’s defense attorney. “And finally you decide you’ve had enough. Time to see what you’ve given up your whole life for, maybe get some of that freedom for yourself. Now look at the people. Tell me which ones are free—free from debt, anxiety, stress, fear, failure, indignity, betrayal. How many wish they were born knowing what they know now? Ask yourself how many would do things the same way all over again, and how many would live their lives like me.”

Jack Reacher’s zipless definition of freedom is practically sociopathic, a life free not just of restraint but obligation, even emotion. (As anyone who’s brushed past a Scientology table in a subway station knows, freedom from “stress” is a key part of the Church’s outreach.) But the movie undergirds Jack’s monologue with stirring, quasi-patriotic music, as if his impactless vision of existence were not, essentially, insane. It’s as if Orson Welles’ character in The Third Man were made the movie’s hero.

The allure of an invisible existence is a constant in Cruise’s filmography. In Mission: Impossible, Vanessa Redgrave’s arms dealer says anonymity is “like a warm blanket.” Jack Reacher says living off the grid “started out as an exercise, and became an addiction.” In Rock of Ages, Cruise plays rock legend Stacee Jaxx, a foundering rock star who, like Cruise himself, is known to all but understood by none. When Malin Akerman’s Rolling Stone journalist tries to get under Stacee’s skin, he taunts her with his own inaccessibility. “I know me better than anyone,” he says, pointing at his face, “because I live in here.”

Cruise’s face plays a starring role in Vanilla Sky, in which his cocky publishing scion wears a translucent prosthetic to cover the scars of a near-fatal car crash. Or maybe—spoiler alert—there are no scars, and there was no crash. The movie replays scenes and shifts between scenarios so fluidly that the audience, like Cruise’s David Aames, is driven crazy, unable to distinguish reality from dream.

What saves David from insanity is not Kurt Russell’s psychiatrist, who turns out to be a construction of David’s mind, but his body. “Accept your body’s resistance,” the fictitious shrink counsels him. “Let your head answer.” (Note that he says “your head” and not “your mind.”) David wants to wake from his “dream,” which turns out to be a scenario implanted by a cryonics firm offering a “union of science and entertainment.” But in order to do so he has to sacrifice his body, metaphorically killing himself by jumping off the top of a skyscraper. Only then can he open his eyes.

In an essay in last week’s New York Times Magazine, Taffy Brodesser-Akner praised Cruise as “the movie world’s most unlikely symbol of old-fashioned authenticity.” But that judgment is rooted entirely in Cruise’s physicality: He does his own stunts, the writer notes; he is “the hardest-working megastar in the business.” (Did you know Cruise did his own stunt driving in Jack Reacher? An army of publicists made sure you did.) In Rock of Ages, the journalist confronts Stacee Jaxx with the old saw that performers are desperate for the audience’s love. But, he sinuously retorts, it’s not love that keeps him going. What, then? “Sex, and other people’s projections of what they want me to be.” He doesn’t exist when he’s not being watched.

Here’s the thing, though. Stacee Jaxx isn’t real, even within the world of Rock of Ages. He’s a persona, a pseudonym made flesh, just like the one adopted by Thomas Mapother IV. Perhaps that’s why Cruise’s highly stylized, glammed-out performance cuts deeper than the grim-faced guardians of Oblivion and Jack Reacher. Stacee is a fraud, and he knows it. Is it Cruise confessing, or him playing off the notion of the disaffected star while secretly loving every minute of it? Cruise keeps peeling back his mask, but underneath is another, and another, and beneath that, maybe nothing at all.