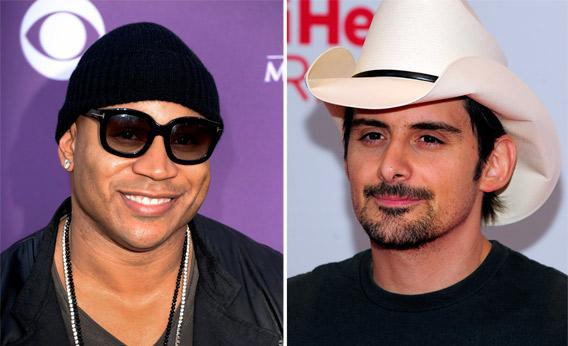

“Accidental Racist.” The title of the new Brad Paisley-LL Cool J collaboration alone is enough to signal “proceed with caution” for discerning first-time listeners. Those words, in that order, read immediately like a cop out, an attempt to side-step responsibility for prejudiced thoughts or actual racist behavior. And the song, with its qualified defense of the Confederate flag and its improbable Lost Cause logic offered up by a hip-hop legend, bear out those fears in rather stunning—if ridiculous—fashion. The video circulating yesterday and this morning has since been removed. You can listen to the song here, with lyrics here.

Paisley begins the confessional country ballad by addressing it to “the man who waited on me/ At the Starbucks down on Main.” This man was apparently offended by the singer’s “red flag” (“red” here meaning Confederate) T-shirt. Paisley is sorry because he’s “just a proud rebel son, with an old can of worms.” This notion, that the Southern past makes many white Americans victims of circumstance, is returned to throughout the song. Paisley says he looks like he’s “got a lot to learn,” but really he’s “just a white man/ coming to you from the south land.” (Nevermind that Paisley is from West Virginia, which was not, in fact, a Confederate state.)

This is not Paisley’s first foray into racial diplomacy. The country crooner has twice performed for the Obamas at the White House, and he wrote an anthem of sorts for President Obama, “Welcome to the Future,” after his election in 2008. In “Camouflage,” Paisley sings about his sympathy for those who find “the stars and bars” offensive, arguing that there are other ways “to show your Southern pride.”

Partly for that reason, after the initial round of predictable online mockery, some have risen to defend the song. Most notably, Alan Scherstuhl, writing for the Village Voice, argues that “smart progressives” who dismiss the song fail to see how brave it is for both Paisley and Cool J to engage Paisley’s fans on this subject. The song’s heart is, as Scherstuhl says, “in the right place,” but that doesn’t mean we should give a prejudiced person a pat on the back for trying and send them on their way. Yes, let’s talk about race. But let’s not endorse a whole bunch of terrible ideas in the process.

Consider another recent attempt at speaking forthrightly about racism. Last month, Philadelphia magazine published a piece by Robert Huber about “Being White in Philly.” “We need to bridge the conversational divide,” Huber wrote, “so that there are no longer two private dialogues in Philadelphia—white people talking to other whites, and black people to blacks—but a city in which it is OK to speak openly about race.” Like Paisley and Cool J, Huber presented himself as brave for taking on the topic. He craved “the freedom,” he said, to tell his “African-American neighbors … how the inner city needs to get its act together.” Paisley at least did Huber one better by collaborating with an African-American neighbor of sorts. But just talking about race is not enough. We need to talk about it intelligently.

In his defense of “Accidental Racist,” Scherstuhl imagines millions of country fans soaking the song in, and gradually becoming more tolerant of black people. It seems just as possible that those fans will absorb all the wrong things from “Accidental Racist”—and there are plenty of wrong things to absorb. Starting with its ideas about the past and personal responsibility, which remind me of a scene in West Side Story: The old shopkeeper Doc furiously says to the young Jets, who are feuding with the rival Puerto Rican Sharks, “You make this world lousy!” “That’s the way we found it, Doc,” one of the gang members sheepishly replies. Sure, the sin of American slavery is in the past, but racism neither begins nor ends with that practice. In the song, Paisley says we’re “fightin’ over yesterday … siftin’ through the rubble after a hundred-fifty years.” Thus he jumps from Reconstruction to the present, as though Jim Crow never happened, as though overt racist don’t happen anymore, as though, in 2013, there aren’t still high school students trying to integrate their prom. Racism—in schools, in the court room, in the hiring process, and elsewhere—still exists, and shouldn’t be dismissed as black people failing to get over something that happened “a hundred-fifty years” ago.

More baffling than Paisley’s well-intended ignorance, though, is the involvement of Cool J, who usually comes off as a likeable and competent hip-hop veteran. In his verse, Cool J implores “Mr. White Man” to understand that, while his chains are gold and his pants are sagging, that doesn’t mean he’s a hoodlum. As the representative of all black American males, Cool J just wants to “buy you a beer, conversate and clear the air,” but that white cowboy hat makes him uncomfortable. Cool J is apparently on board with the idea that the problem between whites and blacks today is based solely on a grudge, as if there aren’t any legitimate reasons these tensions would exist today. “If you don’t judge my gold chains/ I’ll forget the iron chains,” he says, in what may be the song’s single most jaw-dropping rhyme. Putting aside, for a moment, the fact that slavery should not be forgotten, there is, of course, a stunningly wrongheaded equivalency here (and it is not the only one in this song). It should not be necessary to point out that the horrors of slavery are not on the same plane as the sartorial choices of some black males.

Apparently it is. Chains, sagging pants, cowboy hats, red flags: To Paisley and Cool J, the social meaning of fashion plays an out-sized role in racial misunderstandings. This, of course, is an incredibly superficial—and, ultimately, even dismissive—attitude to take toward racism. Paisley and Cool J want to bring us all together, clearly, and that’s an admirable goal. But when that effort ends with LL Cool J saying, “RIP Robert E. Lee,” the cause has been utterly lost, again.