A little more than a week ago, during an interview with Politico, Bob Woodward came forward to claim he’d been threatened in an email by a “senior White House official” for daring to reveal certain details about the negotiations over the budget sequester. The White House responded by releasing the email exchange Woodward was referring to, which turned out to be nothing more than a cordial exchange between the reporter and Obama’s economic adviser, Gene Sperling, who was clearly implying nothing more than that Woodward would “regret” taking a position that would soon be shown to be false.

A rather trivial scandal, but the incident did manage to raise important questions about Woodward’s behavior. Was he cynically trumping up the administration’s “threat,” or does he just not know how to read an email? Pretty soon, those questions tipped over into the standard Beltway discussion that transpires anytime Woodward does anything. How accurate is his reporting? Does he deserve his legendary status?

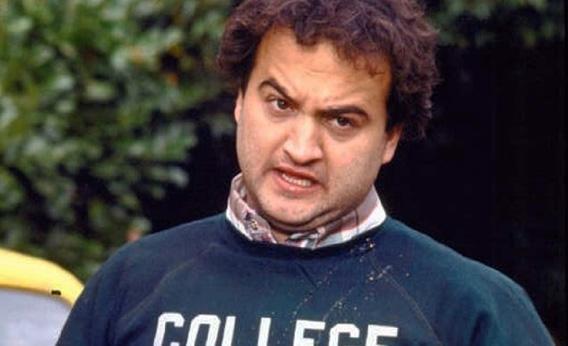

I believe I can offer some interesting answers to those questions. Thirty-one years ago, on March 5, 1982, Saturday Night Live and Animal House star John Belushi died of a drug overdose at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles—which, bear with me a moment, has more to do with the current coverage of the budget sequester than you might initially think.*

Two years after Belushi died, Bob Woodward published Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi. While the Watergate sleuth might seem an odd choice to tackle such a subject, the book came about because both he and Belushi grew up in the same small town of Wheaton, Ill. They had friends in common. Belushi, who despised Richard Nixon, was a big Woodward fan, and after he died, his widow, Judy Belushi, approached Woodward in his role as a reporter for the Washington Post. She had questions about the LAPD’s handling of Belushi’s death and asked Woodward to look into it. He took the access she offered and used it to write a scathing, lurid account of Belushi’s drug use and death.

When Wired came out, many of Belushi’s friends and family denounced it as biased and riddled with factual errors. “Exploitative, pulp trash,” in the words of Dan Aykroyd. Wired was so wrong, Belushi’s manager said, it made you think Nixon might be innocent. Woodward insisted the book was balanced and accurate. “I reported this story thoroughly,” he told Rolling Stone. Of the book’s critics, he said, “I think they wish I had created a portrait of someone who was larger than life, larger than he was, and that, somehow, this portrait would all come out different. But that’s a fantasy, not journalism.” Woodward being Woodward, he was given the benefit of the doubt. Belushi’s reputation never recovered.

Twenty years later, in 2004, Judy Belushi hired me, then an aspiring comedy writer, to help her with a new biography of John, this one titled Belushi: A Biography. As her coauthor, I handled most of the legwork, including all of the interviews and most of the research. What started as a fun project turned out to be a rather fascinating and unique experiment. Over the course of a year, page by page, source by source, I re-reported and rewrote one of Bob Woodward’s books. As far as I know, it’s the only time that’s ever been done.

Wired is an anomaly in the Woodward catalog, the only book he’s ever written about a subject other than Washington. As such, it’s rarely cited by his critics. But Wired’s outlier status is the very thing that makes it such a fascinating piece of Woodwardology. Because he was forced to work outside of his comfort zone, his strengths and his weaknesses can be seen in sharper relief. In Hollywood, his sources weren’t top secret and confidential. They were some of the most famous people in America. The methodology behind the book is right out there in the open, waiting for someone to do exactly what I did: take it apart and see how Woodward does what he does.

Wired is an infuriating piece of work. There’s a reason Woodward’s critics consistently come off as hysterical ninnies: He doesn’t make Jonah Lehrer–level mistakes. There’s never a smoking gun like an outright falsehood or a brazen ethical breach. And yet, in the final product, a lot of what Woodward writes comes off as being not quite right—some of it to the point where it can feel quite wrong. There’s no question that he frequently ferrets out information that other reporters don’t. But getting the scoop is only part of the equation. Once you have the facts, you have to present those facts in context and in proportion to other facts in order to accurately reflect reality. It’s here that Woodward fails.

Over and over during the course of my reporting I’d hear a story that conflicted with Woodward’s account in Wired. I’d say, “Aha! I’ve got him!” I’d run back to Woodward’s index, look up the offending passage, and realize that, well, no, he’d put down the mechanics of the story more or less as they’d happened. But he’d so mangled the meaning and the context that his version had nothing to do with what I concluded had actually transpired. Take the filming of the famous cafeteria scene from Animal House, which Belushi totally improvised on set with no rehearsal. What you see in the film is the first and last time he ever performed that scene. Here’s the story as recounted by Belushi’s co-star James Widdoes:

One of the things that was so spectacular to watch during the filming was the incredible connection that [Belushi] and Landis had. During the scene on the cafeteria line, Landis was talking to Belushi all the way through it, and Belushi was just taking it one step further. What started out as Landis saying, “Okay, now grab the sandwich,” became, in John’s hands, taking the sandwich, squeezing and bending it until it popped out of the cellophane, sucking it into his mouth, and then putting half the sandwich back. He would just go a little further each time.

Co-star Tim Matheson remembered that John “did the entire cafeteria line scene in one take. I just stood by the camera, mesmerized.” Other witnesses agree. Every person who recounted that incident to me used it as an example of Belushi’s virtuoso talent and his great relationship with his director. Landis could whisper suggestions to Belushi on the fly, and he’d spin it into comedy gold.

Now here it is as Woodward presents it:

Landis quickly discovered that John could be lazy and undisciplined. They were rehearsing a cafeteria scene, a perfect vehicle to set up Bluto’s insatiable cravings. Landis wanted John to walk down the cafeteria line and load his tray until it was a physical burden. As the camera started, Landis stood to one side shouting: “Take that! Put that in your pocket! Pile that on the tray! Eat that now, right there!”

John followed each order, loading his pockets and tray, stuffing his mouth with a plate of Jello in one motion.

First off, Woodward wrongly calls the cafeteria scene a rehearsal, when half the point of the story is that Belushi pulled it off without ever rehearsing it once. Also, there’s actually nothing in the anecdote to indicate laziness or lack of discipline on Belushi’s part, yet Woodward chooses to establish the scene using those words. The implication is that Belushi was so unfocused and unprepared that he couldn’t make it through the scene without the director beside him telling him what to do, which is not what took place. When I interviewed him, Landis disputed that he ever referred to Belushi as lazy or undisciplined. “The greatest crime of that book,” Landis says of Wired, “is that if you read it and you’d just assume that John was a pig and an asshole, and he was anything but. He could be abrupt and unpleasant, but most of the time he was totally charming and people adored him.”

The wrongness in Woodward’s reporting is always ever so subtle. SNL writer Michael O’Donoghue—who died before I started the book but who videotaped an interview with Judy years before—told this story about how Belushi loved to mess with him:

I am very anal-retentive, and John used to come over and just move things around, just move things a couple of inches, drop a paper on the floor, miss an ashtray a little bit until finally he could see me just tensing up. That was his idea of a fine joke. Another joke he used to do was to sit on me.

When put through the Woodward filter, this becomes:

A compulsively neat person, O’Donoghue was always picking up and straightening his office. Frequently, John came in and destroyed the order in a minute, shifting papers, furniture or pencils or dropping cigarette ashes.

Again, Woodward’s account is not wrong. It’s just … wrong. In his version, Belushi is not a prankster but a jerk.

Then there’s an anecdote related to me by Blair Brown, Belushi’s co-star in Continental Divide. In that movie, Belushi was cast as Ernie Souchack, a straight-man role in a romantic comedy. On the day they were to film the movie’s love scene, Belushi, not known for his matinee good looks, was terribly nervous. Here’s what happened, in Brown’s words:

If you’ve ever been a part of one of these movie love scenes, they’re just deeply peculiar. … You’re wearing this robe, and all you’ve got under that is this little bitty underwear that you’re going to still be wearing when you do the scene.

I don’t think John had ever done a love scene before, and he was clearly nervous about doing it. He just lay there in bed trying to think up all the funny names for penis that he could: the Hose of Horror … Mr. Wiggly. … We were weeping with laughter it was so funny. It was just like watching a little kid stalling because he doesn’t want to eat his vegetables. “Oh, oh, wait—you know what else? Here’s another one …”

After a while we finally had to say, “Okay, okay, John. Now you have to do the love scene.” He was just stalling and stalling and stalling because he was so nervous.

Here’s the scene as written in Wired:

The script called for a love scene, in bed, in a hotel room. They were to be nude under the covers. John was very nervous preparing for the shooting and kept making jokes, trying to get them to remember all the known names for the male sex organ. They came up with many—“the hose of horror,” “Mr. Wiggly’s dick,” and “one-eyed snake in a turtleneck.” Brown didn’t mind the conversation, but she thought it was an inappropriate prelude to a love scene.

Twenty years later, when Brown told me about the love scene, she was still upset at how Woodward had portrayed it in Wired. “It was my first experience of getting tricked by a journalist,” she said. “Woodward appeared as if he really wanted to know what went on, and I actually had marvelous times with Belushi. But the thing that was depressing when I read the book was that he had taken the facts that I told him, and put an attitude to them that was not remotely right.”

Wired is like that throughout. Like a funhouse mirror, Woodward’s prose distorts what it purports to reflect. Moments of tearful drama are rendered as tersely as an accounting of Belushi’s car-service receipts. Friendly jokes are stripped of their humor and turned into boorish annoyances. And when Woodward fails to convey the subtleties of those little moments, he misses the bigger picture. Belushi’s nervousness about doing that love scene in Continental Divide was an important detail. When that movie came out, it tanked at the box office. After months of fighting to stay clean, Belushi fell off the wagon and started using heavily again. Six months later he was dead. Woodward missed the real meaning of what went on.

Woodward also makes peculiar decisions about what facts he uses as evidence. His detractors like to say that he’s little more than a stenographer—and they’re right. In Wired, he takes what he is told and simply puts it down in chronological order with no sense of proportionality, nuance, or understanding.

John Belushi was a recreational drug user for roughly one-third of his 33 years, and he was a hard-core addict for the last five or six, from which you can subtract one solid year of sobriety. Yet in Wired, which has 403 pages of narrative text, the total number of pages that make some reference to drugs is something like 295, or nearly 75 percent. Belushi’s drug use is surely a key part of his life—drugs are what ended it, after all—but shouldn’t a writer also be interested in what led his subject to this substance abuse in the first place? If you want to know why someone was a cocaine addict for the last six years of his life, the answer is probably hiding somewhere in the first 27 years. But Woodward chooses to largely ignore that period, and in doing so he again misses the point. In terms of illuminating its subject, Wired is about as useful as a biography of Buddy Holly that only covers time he spent on airplanes.

Of all the people I interviewed, SNL writer and current Sen. Al Franken, referencing his late comedy partner Tom Davis, offered the most apt description of Woodward’s one-sided approach to the drug use in Belushi’s story: “Tom Davis said the best thing about Wired,” Franken told me. “He said it’s as if someone wrote a book about your college years and called it Puked. And all it was about was who puked, when they puked, what they ate before they puked and what they puked up. No one read Dostoevsky, no one studied math, no one fell in love, and nothing happened but people puking.”

To get a sense of what Franken’s getting at, here’s a couple of sample entries from Wired’s index:

Belushi, John:

as Blues Brother, 16, 22, 89, 139-42, 146-47, 161-62, 181-82, 186, 206, 334-35

Belushi, John:

cocaine habit of, 15, 17-33, 64-65, 76, 81, 93-94, 100, 103-05, 110, 128, 142-43, 145, 155-56, 159-60, 163-65, 170, 187-89, 193, 205-6, 218-19, 221, 243-44, 247-50, 262, 273, 297, 298, 301, 303, 306-8, 310-11, 316-53, 359, 361-65, 372-74, 385-89, 392-93, 395-400, 413-14, 422

That’s just the coke. It goes on to include “marijuana smoked by,” “mescaline taken by,” and “mushrooms (psilocybin) eaten by.” And those are just the drugs that start with the letter “M.”

Of course, John Belushi did do all of those drugs, and there’s little doubt that the drug stories Woodward uses actually happened. But he just goes around piling up these stories with no regard for what is actually relevant. Just to compare and contrast: At one point, Woodward stops the narrative cold to document a single 24-hour coke binge for the better part of eight pages. Nothing much happens in these eight pages except for Belushi going around L.A. doing a bunch of coke; it’s not a key moment in Belushi’s life, but it takes on an outsized weight in Wired’s narrative simply because Woodward happened to find the limo driver who drove Belushi around and witnessed the whole thing, providing him with a lot of juicy if not particularly important information. Meanwhile, the funeral of Belushi’s grandmother—which was the pivotal moment when he hit bottom, resolved to get clean, and kicked off his year of hard-fought sobriety—that event is glossed over in a mere 42 words, and a quarter of those words are dedicated to the cost of the plane tickets to fly to the funeral ($4,066, per Woodward, as if it matters to the story).

Whenever people ask me about John Belushi and the subject of Wired comes up, I say it’s like someone wrote a biography of Michael Jordan in which all the stats and scores are correct, but you come away with the impression that Michael Jordan wasn’t very good at playing basketball.

It’s not that Woodward is a manipulator with a partisan agenda. He doesn’t alter key evidence in order to serve a particular thesis. Inconsequential details about rehearsing movie dialogue are rendered just as ham-handedly as critical facts about Belushi’s cocaine addiction. Woodward has an unmatched skill for digging up information, but he doesn’t know what to do with that information once he finds it.

All of which helps explain the recent Sperling affair. What did Woodward do? He took a comment from a source, missed or misinterpreted the subtext of what was being said, and went on to characterize it in a way that bore no resemblance to reality. What’s damning about the Sperling emails—and Wired—is that we can go back to the source and see the meaning and subtext for ourselves; normally with Woodward’s confidential reporting, we can’t.

After Wired was published, Woodward said to Rolling Stone that there was some warmth to Belushi that he “didn’t capture,” but he also passed the buck to his sources, saying he tried to get them to “talk about the good times” but kept getting horrible drug stories or stories that didn’t in his estimation reflect the true Belushi. “When you do something like this,” he told Rolling Stone, “you have to learn that people can’t see reality, especially in Hollywood.” I spoke to almost all of those same sources myself. Not only did Belushi’s contemporaries from Saturday Night Live and Hollywood offer colorful tales of a beloved if troubled and complicated man, they themselves are some of the greatest writers, performers, and storytellers of the last quarter-century. They tell good stories. The problem was the filter those stories were put through.

Granted, I wasn’t working from the same notes and transcripts as Woodward. People’s memories change. Stories evolve over 20 years of telling. Surely there were people who were mad at Belushi in 1983 who prefer to look back on him fondly today. And if it were one or two people disputing Woodward’s characterizations, you might chalk it up to rose-tinted glasses. You might do the same if it were nine or 10 people. But when it’s practically everyone, when person after person sits down across from you and remembers, specifically, as Blair Brown did, this is what Woodward mischaracterized and this is really what happened, a pretty clear pattern begins to emerge.

It’s also easy to discount Wired by saying that Woodward just doesn’t have a sense of humor and was out of his depth writing about a comedian. And that’s true as far as it goes. But the stories from Animal House and Continental Divide aren’t really about comedy so much as they’re about human beings interacting, which is a lot of what goes on at the White House, too. The simple truth of Wired is that Bob Woodward, deploying all of the talent and resources for which he is famous, produced something that is a failure as journalism. And when you imagine Woodward using the same approach to cover secret meetings about drone strikes and the budget sequester and other issues of vital national importance, well, you have to stop and shudder.

*Correction, March 13, 2013: This article originally stated that John Belushi died of a “cocaine overdose”; Belushi had taken a speedball, a combination of cocaine and heroin, the night he died, and the coroner’s report concluded that either drug may have been ultimately responsible for his death.