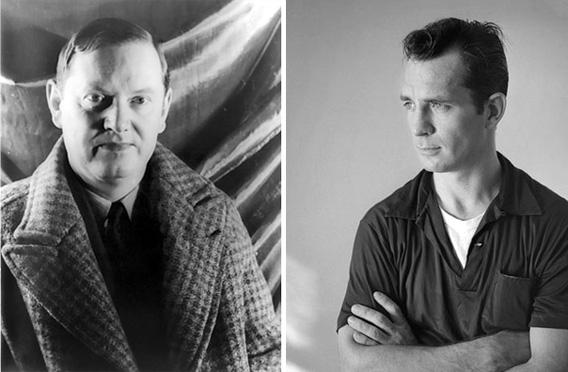

In the corner of the afterlife where they keep the Catholic alcoholic geniuses, Jack Kerouac and Evelyn Waugh are having a lovely time together—patting back and forth some kind of ethereal shuttlecock, reading aloud from Augustine’s Confessions and falling about laughing. … That kind of thing.

Had the two men met here below, however, it is unlikely that the encounter would have been a success. The animus would probably have been on Waugh’s side: Kerouac, blowsy with Beat compassion, might—depending on his mood and booze level—have taken pity on the tightly trussed old fart of an English novelist. Waugh, on the other hand, we can imagine being quite merciless with the younger man, with his emotional incontinence, goofy transcendentalism and so on. Desperate drinking, on both sides, would have been assured.

But in the spirit, where it counts, these gentlemen were tragic brothers. Connective fraternal filaments ran invisibly between them, coursing with information, looping with special intensity around two of their books: Waugh’s The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, and Kerouac’s Big Sur. Two novels, written five years apart, each a skimpily fictionalized account of a terrifying mental crack-up.

The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (published in 1957 and just reissued in a new edition by Little, Brown) was written first, because Waugh went crazy first. Mr. Pinfold is a famous English novelist, aged 50, comfortably situated in a country house not far from London. He is bored to death. He is not writing. He is faintly paranoid. A visit from a BBC film crew unnerves him; in the interviewer’s manner he detects “the hint of the underdog’s snarl.” His memory is doing funny things. Physically, too, he is unwell—overweight and achy, with blotchy hands and a purple face. His pharmacist has given him a “sleeping-draught” (which he dilutes sloshingly in creme de menthe), and his doctor has prescribed some fat gray pills (which he swallows on top of his “normal not illiberal quantity of wine and brandy”). Feeling himself to be going, in a general way, to the dogs, Mr. Pinfold decides—over the protests of his wife—to take a restorative sea cruise. Frowningly, cumbrously, he boards the Caliban and settles in his cabin. At which point—through the floor, or emitting from hidden tubes—the voices begin to assail him.

The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold is inhumanly funny. The ordeal of Evelyn Waugh was anything but. “Going off his head” was one of Waugh’s mortal terrors, and the approach of what he called his “pm”— persecution mania—was perceived with agonizing lucidity. And then he was inside it. On Feb. 12, 1954, he wrote to his wife from the Staffordshire, en route from Liverpool to Port Said, Aden, and Colombo. “It is rather difficult to write to you because everything I say or think or read is read aloud by the group of psychologists I met on the ship.” A week later, still at sea, he attempted a note of condolence to a recently bereaved friend: “I can’t say in the presence of these eavesdroppers how much my heart and prayers are yours. They break into cackles of laughter at any expression of that kind.”

In New York City, on July 17, 1960, Jack Kerouac boarded a train bound for California. His intention—a recurrent one in his case—was to get himself cleaned up. Three years had passed since the publication of On the Road, three years spent largely in a Kerouacian vortex of acclaim and dissipation, radiance and broken-heartedness. A few months before he’d been interviewed on The Steve Allen Show, sweating grimly through rehearsals but then, live, performing with jazzy aplomb a passage from Visions of Cody (the voice of God telling him “Go moan for man, go moan, go groan, go groan alone, go roll your bones … alone”). His acolytes, the offspring of On the Road, were everywhere, all over the country, drinking and drugging, peering through his basement window, offering endless spurious camaraderie. Diminishing returns had set in: Depleted by a thousand binges, Kerouac now wanted—needed, urgently—peace. “One fast move or I’m gone. …” So he was on his way, via his old San Francisco stomping-ground, to the woods of Big Sur, to a cabin offered him by its owner, the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Big Sur was published two years later. Kerouac wrote it in Florida, jamming it out, in the words of Kerouac biographer Ellis Amburn, on “megadoses of Benzedrine.” The book records a period of acute psychological and spiritual disorientation, delirium tremens, the near-destruction of a literary intelligence, starring Kerouac as Jack Duluoz, “bloody ‘King of the Beatniks.’” In Big Sur Ferlinghetti’s rustic shed becomes a cave of bad dreams. Duluoz arrives at night, making his way there through the spooky oceanic dark. He has a couple of nice days pottering around and being whimsical with Nature. Then, feeling expansive, he goes down to the beach one afternoon and takes “a huge deep Yogic breath.” Mistake. Something ineffably horrible attacks him, invades him, he takes a hit of deep-sea Lovecraftian disgustingness, “an overdose of iodine, or of evil … I felt completely nude of all poor protective devices like thoughts about life or meditations under trees and ‘the ultimate’ and all that shit.” And it’s downhill from there.

Both Big Sur and The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, then, deal with literary celebrity, chemical confusion, and the anguish of failing powers; the crack-up, in both cases, was precipitated by a private attempt at a cure. And both authors, as mentioned, were Catholic. Waugh had decided as a young man that a Godless universe was “unintelligible and unendurable”: He converted, and maintained for the rest of his life a prompt and bristling orthodoxy. Kerouac’s spiritual biography is more vagrant, with regular failed emptyings of self into the shining abyss of Buddhism. The older and more messed-up he got, however, the closer he drew to the sentimental-mystical folk Catholicism of his childhood. By the time he wrote Big Sur he had concluded that “life without Heaven” was not to be tolerated.

The real common denominator here, though, is courage: the courage of honesty, and the courage and cunning of the artist in the face of material that is aberrant, language-resistant, and fatally personal. Jack Kerouac had no choice but to let it all hang out: It was his compulsion and his destiny, “because if I dont write what actually I see happening in this unhappy globe which is rounded by the contours of my deathskull I think I’ll have been sent on earth by poor God for nothing.” So here was his naked and blubbering self, exposed, crashing through the panes of sanity in Big Sur. The less-than-compassionate Hunter S. Thompson called it a “shitty, shitty book.” Evelyn Waugh overcame the voices, finally, through strength of will and force of intellect. He subtitled The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold “A Conversation Piece,” relegating his nightmare to the realm of the merely interesting. Their methods were very different. Kerouac had his idiom of blurts and riffs, and his eerie feel for interdimensional slippage or “skidding”; Waugh his indomitable humor and Parnassian superiority of style. But each man, granted a holiday in madness, wrestled it back into a story: He incarnated it. Which might be rather Catholic after all.