“Who gives a shit about this Russian?” David Chase says. The creator of The Sopranos has never understood his audience’s fascination with Valery, the Russian mobster who disappeared in the legendary “Pine Barrens” episode. It was a one-off story that needed no closure, Chase says now. He recalls thinking, “We did that show! I don’t know where he is! Now we’ve got to go and figure that out?!?!”

Terence Winter, who wrote “Pine Barrens” and many of the series’ other memorable outings, agreed with the fans on this one, much to Chase’s frustration, and kept pushing his boss to add a coda to that story in The Sopranos’ final season. They finally hit on an idea everyone would be happy with: Tony and Christopher pay a visit to the local Russian mob boss, where they find Valery sweeping the floor, not recognizing Christopher thanks to a traumatic brain injury suffered when Chris and Paulie were shooting at him. (It would be explained that a local Boy Scout troop found him with part of his skull missing, and saved his life.) At the last minute, Chase changed his mind, and he recalls a despondent Winter insisting, “God, you’re making a huge mistake leaving that on the table!”

But Chase’s disbelief that viewers would want resolution to that story—and his refusal to offer it—do give us clues as to what he really meant by the show’s finale, more than five years ago now. I revisited The Sopranos while writing my book, The Revolution Was Televised: The Cops, Crooks, Slingers and Slayers Who Changed TV Drama Forever, from which the following excerpt is taken. And in discussing the show’s incredible run, and its divisive finale, with Chase, I became more convinced that my initial take on what it all meant was correct.

***

Let’s face it: What drives people nuts in retrospect about this great show is the finale—specifically, the last six minutes of the finale.

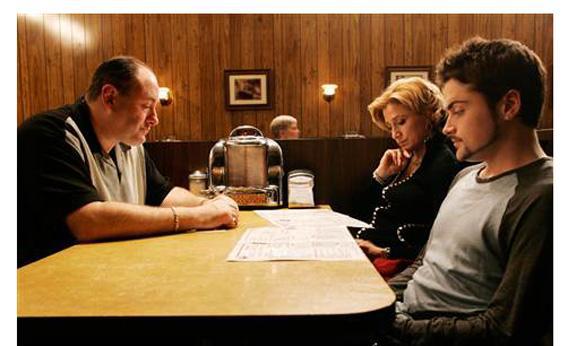

Until we get to Tony, Carmela, and A.J. eating onion rings at Holsten’s ice cream parlor while Meadow struggles to parallel park and a guy in a Members Only jacket goes to the bathroom, it’s a finale very much in line with the way the previous seasons ended, with a mix of plot closure and reflection. Had the show ended on Tony walking away from Uncle Junior, or even on a more conventionally shot and edited family dinner, that episode, that final season, and the series as a whole would be remembered very differently. Instead, it almost feels bigger than the show it dropped a curtain on. It’s a scene that some love and others despise, while even within those groups there’s a deep division over what actually happened when Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” cut off and the picture went to black.

Chase has never been willing to explain the meaning of that final scene—not in the interview he did with me the morning after the finale aired, not in the interview for this book, not in any of his other public comments since the show ended. He says he can’t imagine a circumstance under which he might change his mind. He admits he didn’t realize people would focus so heavily on that final scene at Holsten’s, forgetting everything that had happened earlier in the episode—or, in some cases, the entire series.

“I think that ending so enraged some people that it affected their whole view of the show,” he says. “Why it would, I don’t know.”

Though he always wanted the work to speak for itself, Chase bristles when I suggest that he must enjoy the fact that people are still debating the ending years later, and likely will for as long as anyone cares about the show.

“If I say I enjoy that fact,” he says, “how that gets interpreted is, ‘He’s a sadist. He likes to fuck with people. He’s a mean guy.’ I like to entertain people. I like to give them what’s entertaining, and if it has to be different and it has to rile them up, then it has to rile them up. So if I say I enjoy the fact that people are still analyzing the finale, it will come out as self-aggrandizing, sadistic, and [like] I was always playing head games.

“That show was very, very important to me,” he continues. “Those characters were very important to me. I loved each and every one of those characters. I did not throw them away lightly or deal with them lightly. And it goes all the way from, ‘Oh, it’s so he could do the movie,’ to ‘He got tired, he couldn’t figure it out’ to ‘He just wanted to fuck with us.’ None of that was the case.”

I ask, then, why he chose to present the final scene in the way he did, and his mood shifts abruptly. Any frustration at how he’s been depicted in the media, and by fans of the show he slaved over for seven seasons, vanishes. He is suddenly much quieter, much more uncertain.

“It just seemed right,” he suggests. “You go on instinct. I don’t know. As an artist, are you supposed to know every reason for every brush stroke? Do you have to know the reason behind every little tiny thing? It’s not a science; it’s an art. It comes from your emotions, from your unconscious, from your subconscious. I try not to argue with it too much. I mean, I do: I have a huge editor in my head who’s always making me miserable. But sometimes, I try to let my unconscious act out. So why did I do it that way? I thought everyone would feel it. That even if they couldn’t say what it meant, that they would feel it.”

Based on the reaction to the finale that he’s aware of, does he think people felt it?

“Yeah. I do.”

That said, feeling and understanding are two different things, and he acknowledges that with everyone focusing so much on that abrupt cut to black, something was missed.

“There were filmic things that I was doing there,” he says, “that I wanted to say about life, which people have not really … Only one person I read actually saw it. That’s where the center of the episode was for me, and that’s where the ending was. And people have not connected it.”

And at the risk of also not connecting it, I will say this:

I don’t think Tony dies in the finale—though if you believe that he does, I’ll understand why. Ultimately, I don’t think there is a concrete answer, and I’m no more right than the other side is.

I have read much of the commentary about the finale, up to and including the online essay “The Sopranos: Definitive Explanation of ‘The END,’” which devotes more than 20,000 words to explaining why Tony is absolutely, positively, unquestionably dead. I think there are very persuasive arguments to be made for the idea that Tony is murdered (whether by Members Only Guy or some other unknown assailant) just as Meadow runs into Holsten’s, and that the abrupt cut to an extended black screen is there to make it clear that Tony’s life has just come to an end. There was so much discussion in that final half-season about what happens when you die, about how a violent death can come with no warning. The finale features a lot of death imagery and discussion of death, and there’s no question the sequence was shot and edited in a style that was unusual for the series, designed for maximum suspense. The people in the Tony Dies camp aren’t being unreasonable in the way that, say, the people who said The Sopranos had no business doing dream sequences were.

Photograph courtesy HBO.

But here’s why I would take that same ambiguous ending as Tony living: even factoring in the unusual style with which Chase shot that scene, the idea that Tony dies flies too much in the face of everything the show had previously done in terms of narrative and theme.

Narratively, this was never a show that cheated, or tried to trick its audience. This was never a show told only from Tony’s point of view. We knew most everything going on in his world: who was on his side, who was against him, who was honest and who was lying to him. If a character went to work for the FBI, for instance, we either saw it happen, or it was such a minor character (like capo Ray Curto, so obscure that most fans couldn’t tell him apart from Patsy Parisi) that it didn’t matter.

At the moment Tony walks into Holsten’s, there’s no one we know of who has murder in his heart for the guy. He’s made a deal with new New York boss Butchie; his own inner circle is mostly dead or medically irrelevant; even the one capo who promises to be trouble just sounds like a cooperating federal witness. For Members Only Guy (or someone else in Holsten’s) to be acting on the orders of an enemy we’ve never met (or whom we haven’t heard of in years, like the Russians) simply isn’t the sort of thing the show ever did, and seems too abrupt a shift for the final moments.

Beyond the issue of who did it, the mere idea of Tony’s dying in (or immediately after) the final seconds of the show simply doesn’t seem like the kind of thing Chase would do.

This is a man whose opinion on the idea of story arcs was probably well expressed by Big Pussy, who once told Christopher, “You know who had an arc? Noah.” People kept expecting the series to function like a TV show with a traditional narrative structure, even as the evidence kept piling up, hour after hour, season after season, that this show didn’t work like that. The amount of mental energy expended solely on theories about when and how the “Pine Barrens” Russian would emerge from the woods to rain hell down on Paulie and Christopher—even well after that season ended and it was clear he was never, ever coming back—was so huge it could have solved Fermat’s Last Theorem under other circumstances.

Again and again, the show zigged when we expected a zag. Every cooperating witness would die before they could provide anything of value to the FBI. Seasons would frequently build to what seemed like a huge crescendo, only to offer resolution out of left field. Before Richie Aprile can go to war with Tony, Janice murders him over a punch in the face. Melfi never tells Tony about her rapist. Furio runs back to Italy. And still people expected a familiar narrative.

At the start of the fourth season, Tony confesses to Dr. Melfi that there are really only two ways a guy like him can end up: “Dead, or in the can.” Viewers took the comment as foreshadowing the only two ways the series itself could end, yet whenever I would bring the line up to Chase, he would wince. His view of the show was both too iconoclastic to believe that there were only two possible fates for Tony, each of them a kind of punishment for his misdeeds. Tony had clearly become the villain of his own story by that point; his getting killed in the finale, regardless of who was doing it or why, would be far too predictable an ending, even if the way it was presented (with viewers left to infer the murder based on editing choices and conversations from previous episodes) was unconventional.

Chase doesn’t change his mind often, but if he were to surprise us all one day by publicly admitting, “Yeah, I killed him. Duh,” I would accept that. But barring word from the boss’s mouth, I’m comfortable with my take: Tony’s life goes on, and the only punishment he has to face is continuing to be the fat, miserable fuck that is Tony Soprano. His children won’t be involved in organized crime themselves, but they also aren’t who and what he hoped they would be, and he sees in lonely, penniless, senile Uncle Junior that even a long life for the boss of New Jersey is no great reward.

But the very fact that we’re still having these debates—about both the quality and the content of that final scene—speaks to the boldness of The Sopranos and the mark it left on not only television, but all of popular culture. That Chase would present a scene so open to interpretation—even if, as he insisted to me the day after the finale, “It’s all there”(*)—as his closing statement isn’t something anyone would have expected from a TV show prior to this one.

(*) “It’s all there” could have meant “All the little clues pointing to Tony’s death are there if you look carefully for them,” or he could have meant, “What you saw is what happened, and anything after that is up for you to imagine.” I believe it’s the latter.

American TV viewers had seen great series finales prior to June 10, 2007, and terrible ones, wholly satisfying wrap-ups and cliffhangers that never got resolved due to cancellation, but we’d never seen … this. No one had challenged his audience not only up to the last frame of footage, but for many seconds beyond that. (The most common complaint I still hear about the finale is that it made some people think their cable had gone out.) Chase not only never worried about having a likable main character; he didn’t need a likable series. He didn’t care about giving his audience what they wanted, didn’t need to give them the warm fuzzies in the finale. Instead, he took a kind of scene (Tony gathers the family for a meal at the end of the season) that had been familiar from throughout the show’s run, turned it on its head through music and editing, and either went away by pulling the rug out from under his viewers one last time, or by killing his main character in a way that (barring some kind of deathbed confession or other abrupt change of heart) could fuel arguments from here to the end of Western civilization.