Is That a Glockenspiel?

How a young composer fell in love with the score of Sneakers, and what makes the film’s music so great.

Universal Pictures.

The first time I saw Sneakers in 1992, I was struck by its score. As a 12-year-old classical pianist and aspiring composer, I found myself captivated by the film’s music. I bought the soundtrack and listened to it endlessly. In subsequent years, I’ve even watched the movie with a notebook and sketched out its themes and orchestrations. (Yes, I really have. Sample note: “Whistler says ‘bingo’ and cue begins with quiet violins … main theme … with piano/bell sound? Glockenspiel?”)

Composed by James Horner, the music in Sneakers is hauntingly beautiful and written in a sophisticated and understated manner. But part of what makes the score special is that it doesn’t necessarily sound like what you’d expect for a film in the “computer-hacking / spy-game” genre. It features unlikely elements—choirs, folk themes, minimalist piano, the saxophone of Branford Marsalis—that lend the film an unusual emotional richness and depth. The score does a great job of making you “feel” all of the mysteries that Robert Redford’s Martin Bishop and his merry band of hackers must unravel.

To understand why Sneakers’ score is so uniquely powerful, let’s begin by looking at the opening music featured in WarGames (1983) and Hackers (1995), two other classic movies of the spy-tech-hacking genre.

During the opening credits sequence of WarGames, we’re thrust into the Cold War amid scenes of a secret military outpost housing nuclear warheads. Given that the film stars Matthew Broderick as a boy who almost starts a nuclear war by hacking into the U.S. military’s computer network, it makes sense that the opening music is ultra-militaristic. As we watch scenes of military trucks and soldiers guarding NORAD, we hear a huge ensemble playing a bold and rousing brass fanfare:

Let’s now watch the opening credits sequence of the film Hackers, another classic of the genre:

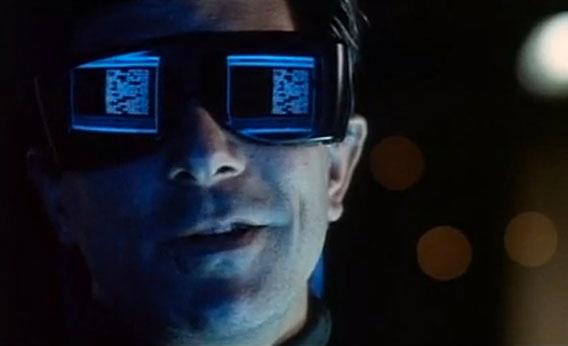

Here we see Dade “Zero Cool” Murphy (Jonny Lee Miller) on an airplane approaching New York City, seven years after his criminal conviction for hacking into the New York Stock Exchange. The musical accompaniment, Orbital’s “Halcyon+On+On,” is amorphous and synthesizer-based, slowly evolving into an electronica beat which pulsates under the scene. Right at the opening, we get a clear sense of the “electronic” themes of the movie and of the hacker counter-culture we’re going to explore.

Let’s now watch the opening credits sequence of Sneakers, which takes a more surprising tack:

On-screen, we see a flashback of Martin Bishop (Robert Redford) leaving a building just before his friend Cosmo (Ben Kingsley) is caught by the police for hacking into the Federal Reserve’s transfer network. While the music feels hushed and mysterious, it is also unexpected. The opening string melody of descending sixths sounds almost like Eastern European folk music, haunting and wistful. While these strings are playing this folklike sound, we hear quiet murmurings of flutes, piano, and choir. The effect creates a kind of halo around the hacking of the Federal Reserve, making it seem like an elevated endeavor. Far from brassy militarism or counterculture synth, the music actually sounds dreamlike and lyrical. As the music develops, the gorgeous sound of Branford Marsalis’ soprano saxophone enters and provides a feeling of jazzy sophistication and emotional depth.

Instead of simply emphasizing the fact that the police are about to catch Cosmo—with, for instance, pulsing drum percussion and sustained, ominous strings—the music presents us, right from the outset, with a set of more complex emotions. There is something melancholy in the air, something regretful. We begin to understand the relationship between Cosmo (who gets caught) and Martin (who escapes) in a way that would be completely lost had the music simply reinforced what was already clear on the screen.

Here’s another example of unexpectedly subtle and beautiful music:

This music is from the scene in Sneakers in which Martin Bishop and his crew begin to decipher that “Setec Astronomy”—the research project of a mathematician they’ve been pursuing—is actually an anagram for “Too Many Secrets,”—a hint that they’re on the trail of a codebreaker. At first, we hear a simple yet catchy piano theme repeated over and over. As it continues repeating, a second piano line joins in as a partner to it. The music is quiet yet densely populated with short little piano notes. The music feels like a perfect counterpoint to what is taking place on-screen: The characters are uncovering a secret. As if speaking to this, the music is soft, almost whispered, enhancing our feeling of the mystery about to be unlocked.

Beyond just conjuring up a sense of elevated mystery, Horner’s subtle, minimalist music also underscores the film’s ideas about computer technology. At the end of the film, Cosmo lays out his grand view of the future: “The world isn’t run by weapons anymore, or energy, or money, it’s run by little ones and zeroes, little bits of data. It’s all just electrons.” Horner’s dense texture of uniform repeated notes feels like the “little bits of data,” the “ones and zeroes” that are at the heart of the film’s drama. Listening further to the piece in the “Setec Astronomy” scene, we see the music continue to develop: one, two, then three different pianos playing along simultaneously. As the characters get closer to deciphering the code, more and more musical elements join in: female choir, harp, strings, woodwinds, percussion. We really begin to feel viscerally the newfound power of these “little ones and zeroes.”

The choices a film composer makes can either reinforce the drama on-screen, or they can move in contrary motion to it. I’ve always felt that the best film music does both: It emphasizes the story onscreen and creates its own parallel story. To me, the Sneakers score endures because it does exactly this: supporting the action while overlaying the film with a veneer of quiet beauty and unexpected elegance that lends a sense of richness and complexity to the characters and their drama.

Like the film itself, admired by a small coterie of enthusiastic fans, Horner’s score for Sneakers is often overlooked; it seems to get overshadowed by the more famous and widely acclaimed projects he has worked on. Horner has written iconic music for such films as Field of Dreams, Braveheart, Glory, Aliens, and—of course—Titanic and Avatar, so it’s understandable that his Sneakers score might get eclipsed. But 20 years later, now that I’m working as a composer, I keep coming back to it. And actually, I’m pretty sure that wasn’t a glockenspiel: It was a celesta and a harp.