In 1990, the Fat Boys sued Miller Brewing Company for, among other things, unlawful use of the “Hugga-Hugga.” Lite Beer had appropriated this beat-boxing sound—invented inside the mouth of Darren “Buff Love” Robinson—for a 1987 TV ad featuring a weirdly caramelized Joe Piscopo looking like he’d swallowed an inflatable exercise ball. In the pursuant legal brief, the Hugga-Hugga would be cited alongside the Fat Boys’ signature “Brrr,” the alveolar trill of a tongue that sounds conversant in bank alarm. The suit also referenced Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, Inc., Garbage Pail Kids vs. Cabbage Patch Kids, Pussycat Cinema, Superman, and Crazy Eddie—a Brooklyn-based stereo chain that did its part in enabling the Hugga-Hugga to be heard throughout the Tri-State area. The judge ruled in favor of the Fat Boys.

More mocked than understood, the noises at stake in that lawsuit can be heard in all their thunder and glory on “Stick ‘Em,” a track from the Fat Boys first album, revived this month by Traffic Entertainment. The CD reissue comes in a pizza box, a triumph of packaging that could hold a 6-inch mini (thin crust). Pictured on back of the brown cardboard is Buff Love, anchovy-sized in prison stripes, preparing to take a bite out of the Unicode recycling arrows. It’s a tribute of sorts to the Human Beat Box, who died of cardiac arrest in December of 1995.

When the pizza box arrived, I spent most of the day opening and closing it, as if making sure the thing actually worked. I wanted to tell everyone about it, just to say the words “Fat Boys pizza box.” It made me nostalgic for brilliant marketing strategies from hip-hop’s past. It made me want to say things like “Alkaholiks barf bag.” “Three Times Dope knee-pads.” “Ice Cube Lethal Injection hypodermic ballpoint pen.”

The pizza box is a fitting tribute. Buff, Prince Markie Dee (Mark Morales), and Kool Rock Ski (Damon Wimbley) were hip-hop’s first brand, jumping out of helicopters in Swatch commercials and demolishing buffets in movies. (A spit-bucket was retained for the famous Sbarro buffet scene in Krush-Groove—no pizza was actually digested during filming; appetites may have been lost.) Size, the exaggerated framing device of that brand, suited the hyperbole of the Fat Boys career: They earned $5.7 million as teenagers but lost it all by adulthood. Morales prolonged his career by taking up New Jack Swing and writing “Real Love” for Mary J. Blige a year after Robinson stood trial for corrupting the morals of a minor in a videotaping scandal. Wimbley turned to fitness, with ambitions of developing his own protein shake and releasing a workout video with Biggie’s small fry associate Lil’ Cease. He would later joke that the Fat Boys could be reunited as The Ex-Fat Grown Men.

The Fat Boys’ mentor—and the owner of the brand name—is a Swiss-born promoter named Charlie Stettler. In 1982, Afrika Bambaataa, a DJ of esteemed heft and taste, turned on Midday with Bill Boggs and saw a man in a gorilla suit promoting a cassette that contained recordings of garbage trucks. The gorilla, Stettler, had sold over 200,000 tapes of “noise for homesick city dwellers,” released through his label-management company Tin Pan Apple. The following year, he put on a talent show at Radio City Music Hall, and the Fat Boys—then rapping as Disco 3—were the unexpected walk-on champs. Stettler took the group to a yodel-off in his native Switzerland, figuring, as he put it, “If you can get those assholes”— he meant the Swiss yodeling fans—“to nod their heads and smile, then you might have something.” Farmers on a mountain north of Zurich witnessed Buffy doing a beat-box version of “My Country Tis of Thee.” And though they arrived in Europe as the Disco 3, the group flew back to New York as the Fat Boys, after raiding the hotel kitchen and, so the legend goes, sticking their manager with a 375-franc tab, as well as a multi-million-dollar idea.

Stettler got Swatch to sponsor 1984’s Fresh Festival Tour and convinced Russell Simmons to add the Fat Boys to a line-up that included Run-DMC, Whodini, and Newcleus, all of them performing among green lasers and pastel Swiss time-pieces in front of a Keith Haring backdrop. (Having attended Fresh Fest I in Charlotte, N.C., I am grateful to the grave for Stettler’s gorilla-suit hustle.) During the ensuing media blitz, Stettler advised the Fat Boys to yell “Brrr! Stick Em!” if they were unsure how to answer a question. The trademark became a drill.

But the name-branding and Chubby Checker collaborations shouldn’t diminish the early recordings, put to tape when the Fat Boys were just talented teenagers who could flow. “Can You Feel It?” is an electro-funk classic. Producer Kurtis Blow—then in “Basketball” form—enlisted Run-DMC drum-machine programmer Larry Smith and bassist Davy “DMX” Reeves, both of whom were behind some of the best records of the era to work on it. (They often collaborated with a session drummer named Pumpkin, AKA “B. Eats.”) Rick Ross apparently still knows the entire Spider-Man verse from “The Place To Be,” another spare treat. Many people—including the Fat Boys themselves—were dismissive of their first single “Reality,” but the James Mason-arranged music behind their rhymes could be a lost John Carpenter track. (A keyboard player for Roy Ayers, Mason recorded some fine interstellar space-cruiser ballads on his own.)

According to Wimbley, the original lyrics to “Jailhouse Rap,” the first track on the debut album, were toned down; stories of shooting cops in the back turned into stories about “getting arrested for doing something stupid related to food.” While Run-DMC strutted in fedoras and Adidas, the Fat Boys were having food fights in bathing suits and inner tubes. Their namesake single, “Fat Boys,” produced by Kurtis Blow, was pretty hardcore about being soft in the middle: In the video, Kool Rock Ski wore a functional bright green umbrella hat while Buffy beat-boxed into an ice cream cone, possibly pistachio. At the height of the group’s popularity, it was not uncommon for women—many of them older—to ask Buffy to Hugga-Hugga into their cleavage.

Mention the Fat Boys around the office and you’ll get instant recognition in the form of fake hyperventilation and motorboat sputter—an unflattering impression of a talented kid essentially killed by his own brand. What often got lost in the clowning was Buff’s impossibly deep bass register, which made him sound as if he’d swallowed a subwoofer. When the Fat Boys toured Europe and the states, Buff left behind a wake of blown speakers and astonished soundmen. (Though Doug E. Fresh was master of the clicks, “Buff,” as Biz Markie once declared, “was Bass.”) It was said he could shake a classroom from the hallway. He could also make your stomach vibrate—as if just being in the presence of beat boxing could make you hungry. Buff’s leather motorcycle jacket, studded in forks and spoons, is now in the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame. The rhinestone-framed Cazals are still the best picture windows in hip-hop.

I’ll never listen to “Are You Ready for Freddy?”—it’s not the Fat Boys best effort—but I love that Robert England tore off his prosthetic nose on set while filming the video and gave it to Markie Dee as a souvenir. I like the idea of one of the Fat Boys having Freddy Kreuger’s nose boxed up in storage. I like to think that Disorderlies is always playing somewhere on late-night cable during a late-night snack, that someone is watching Buff Love do an emergency cannonball into a pool to extinguish a hissing dynamite fuse to save the day.

But real affection for such silliness goes hand in hand with respect for what the Fat Boys accomplished. The other day I saw a subway ad for the social networking site Badoo. It was a mock profile in bad spoken word, a young woman talking about beat-boxing while eating a burger. The Hugga Hugga deserves a better legacy.

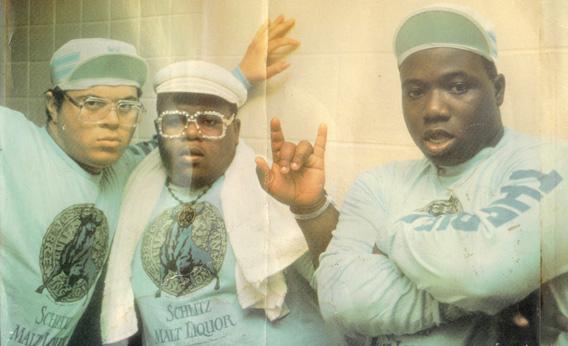

The Fat Boys made some great records. They also managed to make me laugh after my apartment nearly burnt down. I was ankle-deep in soot and water when I heard a member of the NYFD say, “Hey—the Fat Boys!” His flashlight had hit on a backstage photo of them in matching Schlitz Malt Liquor sweatshirts. I tell this story often, as the fire is a good excuse to talk Fat Boys, and to brag about that photo. It currently hangs on the wall outside the door of my fourth-floor apartment. That way I can instruct visitors to keep walking until they run out of stairs and see the Fat Boys. Because sometimes I just like saying the name.