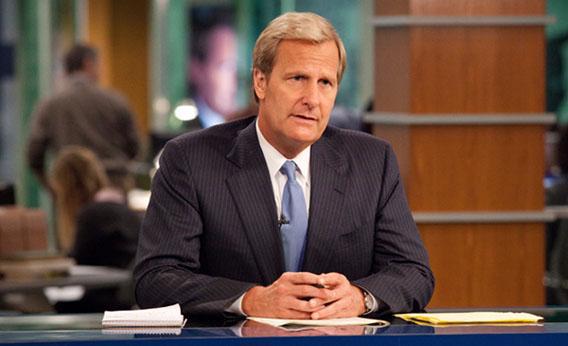

Aaron Sorkin’s new HBO series The Newsroom is set in the world of cable news, following the staff of the fictional News Night, hosted by anchor Will McAvoy (Jeff Daniels). I spent almost eight years working in cable news before I decided earlier this year to exit the industry in a quiet, dignified fashion, so naturally the show piqued my curiosity. The series is getting mixed reviews, but as far as verisimilitude goes, Sorkin deserves credit for nailing a lot of the details of the milieu. But given how many of the little things he gets right, it’s surprising that he gets a few of the big ones so wrong. Herewith, a guide to accuracy of The Newsroom:

What Sorkin Gets Right:

The newsroom itself: The show’s main set, with its soaring ceilings, natural light, and gleaming glass and metal surfaces bears no resemblance to the newsroom at Fox, where I used to work. (That place is a cramped, bed-bug-infested, subterranean former Sam Goody store.) The News Night HQ does, however, look quite similar to the modern, spacious facilities that CNN has within the Time Warner Center. (I was lucky enough to see them a few months ago right before the great Howard Kurtz methodically flayed me alive during an interview.)

The computers: The industry-standard software Avid iNews is clearly visible on the monitors of the News Night staffers. The program is used to create the rundowns—the shared spreadsheet that acts as a blueprint for the show. The rundown contains the script, guest names, lists of video and graphical elements, as well as an estimate of how long each segment will take. As Sorkin shows in the pilot, iNews also spits out story alerts from the Associated Press and other wire services, color-coded by importance—yellow, orange, red and so on. The Newsroom gets this right, down to the correct sound effect the program makes when an alert comes in. (One niggling detail that the pilot gets wrong is the amount of attention paid to the news alerts. Literally hundreds of them come in every day, and roughly 90 percent of the bulletins are something minor, like state lottery numbers. Most producers turn off the sound effects.)

The dress code: In the pilot, the dickish executive producer Don struts around the office in an untucked flannel shirt and jeans, while the earnest senior producer Jim—one notch lower than Don—is nerdy-chic in a suit and an ID badge suspended on a lanyard. The muddled dress code is true to a cable news workplace, where two competing aesthetic dynamics clash: the inherent schlubbiness of journalists and the flashy polish of television personalities. Tech guys in Jets jerseys work side-by-side with anchors in Armani suits, and everyone else is somewhere in the middle. I once had an intern who wore double-breasted suits every day, and when we greeted guests who didn’t know any better they would often mistake him for my boss. It probably didn’t help that I only shaved twice a week.

The Luddite anchor: One of the most effective running gags in the pilot episode involves McAvoy repeatedly expressing amazement that he has a blog, which is run by a young staffer. This is dead on. My old boss has a website, which he’s certainly aware of, since he steers people there every night to buy branded merchandise. It’s still an open question whether or not he’s aware that he has a Twitter account with almost 200,000 followers. (That’s not to say that this is the norm, however. Lots of TV journalists—Jake Tapper, Chuck Todd, and Greta Van Susteren come to mind—are prolific online, writing their own blog posts and tweeting furiously.)

The “back-in-my-day” old guard news honcho: The news division president, Charlie, played by a feisty, bow-tied Sam Waterston, tends to ramble on with stories about the past. (At one point he actually prefaces a story with “In the old days …”) While this is a well-worn character archetype, it’s also true to reality. Fox News president Roger Ailes is known for regaling staff with stories about his TV past during speeches at company functions. I personally heard at least three retellings of the time he worked for The Mike Douglas Show and had to set up a functioning bowling alley in the studio with less than 24-hours notice.

The relationships: Sorkin nails the boozy camaraderie and constant flirtation that develop between cable news co-workers. The News Night staffers’$2 8 p.m. live show leaves them little time for a social life aside from drinking with co-workers after the taping. (I once worked for a show that taped at 10 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Both my girlfriend and my liver hated me the entire time.) He also accurately portrays the strained dynamic between a multimillionaire anchor and his underlings: McAvoy can’t remember the names of any of his crew, and angrily berates them when they don’t do their jobs right. Sound familiar?

What Sorkin Gets Wrong:

The Newsroom can be read as Sorkin’s attempt to cure what’s ailing the news industry, but he’s misdiagnosing the patient. In the universe of the show, the biggest knock against News Night is that Daniels’ McAvoy is too safe, too middle-of-the-road, too afraid to offend or rock the boat. (He’s repeatedly, disparagingly compared to Jay Leno.) McAvoy’s new executive producer MacKenzie (Emily Mortimer) urges the anchor to take more risks, become more opinionated, and stop covering fluffy stories, ratings-be-damned. McAvoy, who has been enjoying the highest ratings at the network with his tame, anodyne broadcasts, worries that if he turns into a tough guy his viewers will flee in droves. But ultimately he goes along with the new plan, rebooting News Night with an on-air apology to his viewers for not covering more substantial topics. He starts to get more confrontational, and feels invigorated by the change, but—as he feared—the numbers start to drop.

Of course in reality, the problem with cable news isn’t that anchors are too timid, or loath to offend for fear of losing viewers. It’s the exact opposite. Most modern cable news hosts are actually quite eager to stir the pot, believing that opinion and controversy are the things that drive higher ratings. And the data backs up that view: Fox, with combative anchors who are drifting even more to the right as the election approaches, is still No. 1, while the decidedly straight-down-the-middle CNN hit record-low ratings last month.

The Newsroom also fundamentally misstates the centrality of ratings in the cable news industry. When News Night’s ratings dip due to McAvoy’s new on-air persona, it draws the ire of Reese (Chris Messina), a reptilian corporate stooge with his eye on the bottom line. He tries to convince the anchor to moderate his stance to win back viewers. To keep his colleagues in the dark about his desire for increased popularity, McAvoy insists on meeting with the executive in secret, outside the office, Deep Throat style. In the world of The Newsroom, the quest for ratings is portrayed as shameful, something that only the bean counters should care about, and that any serious journalist should ignore.

But in the real world, every single cable news employee, from the CEO down to the lowliest intern is acutely aware of—or in some cases obsessed with—the numbers. At Fox, every afternoon at 4:30 p.m. an email goes out to a massive distribution list of senior staff and talent; attached is a spreadsheet with 20 pages of ratings data from the previous day’s programming, for every show on the network, as well as every show on CNN, MSNBC, and Headline News. The data is broken down into 15-minute increments then sliced and diced into various categories—total viewers, viewers aged 25 to 54, live viewers, DVR viewers, and so on. Producers, executives, and, yes, anchors, pore over these numbers with Talmudic devotion, and adjust the programming accordingly. I’ll let other people argue whether this practice is good or bad for journalism. But for Sorkin to ignore this aspect of the industry is baffling.

Not that any of this ruins my enjoyment of the show. I agree with a lot of the early criticism of The Newsroom, but I’m also a lot more sanguine that Sorkin can turn it around by the end of the season. Then again, maybe it’s impossible for me to be objective about a show that portrays my old profession as heroic, when I departed that profession in such a less-than-heroic manner.