You may well have never heard of the mega-popular British boy band One Direction before their appearance on Saturday Night Live a few months ago. After all, their first album, Up All Night, was released less than a month before that. (It became the first debut record by a British artist to enter the Billboard Top 200 at No. 1.) And while their first North American tour sold out so quickly that they immediately lined up another one for 2013, less than two years ago band members Niall Horan, Zayn Malik, Liam Payne, Harry Styles, and Louis Tomlinson were complete strangers to one another. Then Simon Cowell and Nicole Scherzinger formed the boys into One Direction on Britain’s reality TV show The X-Factor.

So you could be forgiven if you’re just getting into the band, and if the only song you really know by One Direction is their ubiquitous single “What Makes You Beautiful.” But you know who wouldn’t forgive you? Directioners, that’s who.

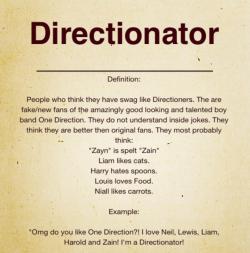

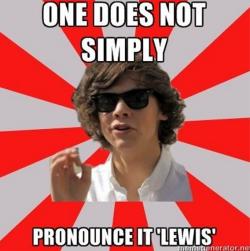

To die-hard One Direction fans—self-professed Directioners—fans who’ve just discovered the band or only know their hit are Directionators. If you can’t name all the band members or spell their names correctly, you’re a Directionator. If you think that Louis (tip to Directionators: it’s pronounced “Louie”) really likes women who like carrots, or if you somehow think that Liam likes spoons, then you are a Directionator. And if you peruse the multitude of rants and “Shit Directionators Say” videos on YouTube, you’ll understand that you are ruining everything for the true fans that have been tirelessly laboring in the trenches of 1D fandom for nearly two dozen months. If you’re a Directionator, you are unworthy of “the boys” as well as the ticket you just bought to see them in concert next year.

Of course, superfans have been suffering dilettantes forever. Punks and metalheads have long been hostile to poseurs who merely listen casually to the music or adopt the fashion without living the lifestyle. Directioners grant status to early One Direction adopters; Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians would have been a “Shit Backsliders Say” video had YouTube been available. But what’s unique about the Directioner/Directionator divide is the speed with which it has taken place, and the way that social media and Internet-fueled celebrity culture has fed it.

Courtesy http://ziallersunite.tumblr.com

A generation ago, indie music fans relied on small rock clubs, fanzines, and savvy friends to catch bands before everyone else. Pop idols were often created by producers in a manner similar to the way One Direction was thrown together, but the young target demographic never heard them until their records had been distributed to radio stations and MTV for massive airplay and advertising. By contrast, One Direction fans have had the opportunity to vote the band from obscurity to a record deal themselves. And after The X-Factor (One Direction placed third), fans took their obsession online, following the band on Twitter in massive numbers (nearly 4.5 million so far), Tumbling every photograph, posting links to foreign interviews, and creating YouTube videos of their love of the boys. As a result, One Direction was already a sensation in America before they’d even arrived here. “It’s a real moment,” the director of One Direction’s British label has explained. “Social media has become the new radio, it’s never broken an act globally like this before.”

It’s no surprise, then, that social media is now where Directioners are trying to draw the line between themselves and the new fans they despise. Between the intense sentiment of Directioners and the velocity of social media, the result is a fan base that excoriates would-be fans for the merest of slights or for not knowing the most trivial of facts—all in a frantic attempt to keep One Direction for themselves as they become an arena-sized pop juggernaut.

A scene in the film High Fidelity epitomizes the paradox of the superfan. Aging hipster record store owner Rob Gordon (played by aging hipster John Cusack) announces that he will sell three copies of The Three EPs by The Beta Band. Rob wants to use his knowledge about an obscure band to impress his friends—it’s his power. At the same time, the only way to demonstrate this is to make the band more popular, therefore diminishing his strength. Directioners are experiencing this painful realization in real time on the Web: All their tweets and Tumblrs have evangelized the band beyond the One Direction Nation, and the band no longer belongs to them.

Courtesy http://cupcakesandbbqchips.tumblr.com

Rob Gordon and indie music fans everywhere can shed ironic tears for the latest underground favorite to get co-opted by the mainstream—they know there are other bands out there waiting to be discovered. But for most of these young Directioners, One Direction is their first love. It’s telling that although the boys of One Direction are sex symbols, the fans also have a nurturing, almost maternal, relationship to the band. The social Web has given them a feeling of ownership over One Direction, and they feel responsible for the band—and for the other fans that they’ve inadvertently helped to create. They insist that every member is equally valuable and good-looking. “THEY ARE ALL WONDERFUL. One isn’t better than the others. So get over yourself and like all of them, not one. 5 boys, One Band, One Direction,” asserts a Directioner Tumblr. They believe in the intrinsic value of each and every one of One Direction’s songs, and pride themselves on having an encyclopedic knowledge of them. They defend the ethnic identity of half-Pakistani Zayne. They even bravely love the boys’ girlfriends because they seem to make the boys happy: “You can’t call yourself a real Directioner when you hate on the boys girlfriends. Real Directioners love Danielle and Eleanor because they make our boys happy, and we don’t send them hate.” Many Directioners have taken a cue from the band’s playfully affectionate behavior with each other and seek to defuse the homophobic slurs of haters by asserting that they would, in fact, be fine if all the boys weren’t straight. Some, like the Tumblr Niallerlightsupmyworld, declare that indeed, the boys are gay: “If you get mad when someone calls One Direction gay … you’re obviously not a true Directioner. True Directioners know that they’re all gay for each other.”

For Directioners, anything that might harm the band or their relationship to the band is roundly and publicly criticized, and enemy No. 1 is new fans of the band. As @1DOvariesKiller says in her breathless YouTube rant about Directionators who dare to criticize a member of the band, “Go sit. Go sit in your irrelevant-ass corner, where you are banned from this fandom.” Chief among the crimes committed by Directionators is that they discuss the band on Facebook—i.e., not Tumblr, so the wrong social channel. In a Tumblr post “To all Fake Directioners,” a fan berates people who “SPREAD THE GLORIOUS BEAUTY OF 1D AND BEFOUL THEIR BEAUTIFUL NAME BY POSTING THEM ON FACEBOOK” and “SPEAK OF THEM OUTSIDE TUMBLR TO OTHER MORONS. HENCE CREATING A CHAIN OF FAKE DIRECTIONERS.” Of course, Directioners don’t see the irony of complaining in social media about how Directionators use social media—the stakes are simply too high for them. If the boys are somehow lost, they think, they may never find another band to love.

Courtesy http://x1dlightsupourworldx.tumblr.com

But the tragedy is that it’s already over for Directioners, whose fandom was perfect for a fleeting pop-culture moment, but one that has already passed. Soon everyone in the world will have heard the band, and thanks to the endless tweets, Tumblr posts, and YouTube videos, everyone will also know that Liam has a phobia of spoons and that Louis was just joking when he said that carrot eating was the chief thing he looked for in a girl. As allykilpatrick1598 mourns at the end of her YouTube rant against Directionators, “We never thought they would get this big … but we have to face it … It’s not going to be the same from here onwards.”

In an information economy that moves with the speed of a text message, the life cycle of any pop-culture phenomenon is increasingly going to be measured in months and weeks instead of years, turning even the youngest fans into cranky hipsters, snarkily guarding their own cred, creating arbitrary divisions to preserve their status. More and more young fans will close their YouTube missives not with breathless professions of love, but in the way allykilpatrick1598 does: “I have one more word for you Directionators: LEAVE!” These teen girls are among the very first never to have known a world without Facebook, Twitter, or other social media platforms as a constant source of information, and even more, a constant pressure to broadcast and define yourself—to establish your personal brand—in the most public way. It seems a harbinger of things to come: A future in which we will, at all times and about all things, be either Directioners or Directionators.