A few weeks ago, it was reported that Spotify, the music-streaming service, is introducing a new “Private Listening” setting for those that wish to not have their “guilty pleasures” broadcast on Facebook, which would make for a good lead to an Onion article, if only it were satire. Apparently, it’s not; just ask the many twentysomethings who were caught listening to Maroon 5—nobody was laughing. Because Maroon 5, unlike, for instance, Lady Gaga, cannot be perceived as deliciously awful; it can only be awfully awful. One is sentimentality dressed in drag, and the other is just plain sentimental, like the cultural equivalent of not being in on the joke—a hipster nightmare.

But if Henry Miller was right, and a lie reveals more than a truth, then a “guilty pleasure” reveals more than a stated pleasure, which means, often, there’s a difference between what you say you love, and what you really love. And the need to be accepted in the right club never goes away. If that club is related to the arts, or at least is “artsy,” or “artistic,” or “literary,” then you’ll need cultural capital to increase your standing.

So it figuratively pays to go on at length about your love for, say, Jonathan Franzen, because Franzen conveys an enlightened cultural, liberal sensibility. Everyone in this club is definitely cool with him, just as they’re definitely cool with Werner Herzog and Radiohead and farmer’s markets. It does not pay to go on at length about your love for The Hills or Keeping Up with the Kardashians unless you’ve proven yourself to be a true cultural omnivore, equal parts elitist and populist, the kind of person who thoughtfully considers Tolstoy at 8 o’clock and intellectually justifies checking into The Real World at 10. This is sort of like reaching the highest level of Scientology, in which you can move objects with your mind.

Yet, maintaining omnivore status requires a heavy dose of self-consciousness, and is just another way to combat the guilt of finding joy in what is dismissed as vapid “low-brow” entertainment. So the clubs that really matter are the ones built on guilty pleasures, because a guilty pleasure makes you feel fraudulent, and therefore ashamed of yourself. And what you are ashamed of, you keep secret, especially if it doesn’t jibe with your public persona and especially if it doesn’t jibe with your own fragile self-perception. The guilty pleasure is perhaps the most honest thing about you, and in time you will feel alienated by it, alone, until you reach a breaking point, which is confession.

This confession has a very specific purpose: to recruit others to your team in order to alleviate the guilt. You whisper around the margins of your club: “Did you see last night’s episode of Bachelor Pad?” The first person you ask grimaces. “Me neither,” you say, hiding your embarrassment. “Just hoping someone would tell me about the show. I heard it’s crazy.”

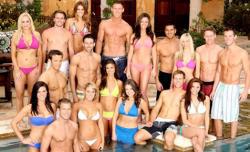

Eventually you find an ally, and then another, and another. You build a kind of guilty-pleasure support group, a safe zone in which you chat about Vienna, the backstabbing whore, or Blake, the asshole. The group grows until it is no longer just a group, but a legitimate club. There is consensus. Bachelor Pad is good television, enjoyed by smart people. It poses relevant philosophical questions: What is love? What is reality? Is love no longer a reality? Is the human race doomed? And just like that, Bachelor Pad is no longer a sin, but a show of real anthropological significance.

Of course Bachelor Pad has no anthropological significance whatsoever. It is probably the worst fucking show on television. I watch it, and I feel badly about myself for watching it. Just as I feel badly about watching Jersey Shore and The Bachelor and The Bachelorette. Friends of mine have questioned my motives, as I’ve told them repeatedly that to not watch these shows is to be “out of step with America.” It’s a lame defense, and it’s also a lie. I do not wish to be “in step with America” any more than I wish to be in step with people who talk about “emotional walls” or those who “beat up the beat.” I know others who make this argument, too, and they are also liars. It’s an attempt to assert intellectual superiority through reverse psychology, and it hinges on two implied questions: 1) “Are you so insecure, you can’t engage with anything that is not obviously ‘smart’?” and 2) “Do you think you’re better than reality television?”

The truth is, we’re all better than reality television, at least the kind I’m referring to here, which doesn’t necessarily appeal to the lowest common denominator, but rather focuses on people of the lowest common denominator. I sometimes wonder if they are not the saddest people on earth, the characters of these shows. We say we watch them because it’s like a “train wreck,” or because they “make us feel better about ourselves,” but really we’re perpetually intrigued by, and obsessed with, the lurid toxicity of fame, which is reality television’s only true subject.

How far will one go to achieve fame? Evidently pretty far. I’d give examples, but it’s too exhausting. I envision the cast members of these various shows and am certain they are not a “reflection of America.” They’re not even American archetypes, which is the territory of scripted television. These are damaged human beings who would rather die than live in obscurity or else get a job. But then again, this is the most interesting aspect of taste in a postmodern democracy: With the right numbers, and the right positioning, you can ultimately justify anything.