The Black Film Canon has now been updated: Check out the New Black Film Canon.

#OscarsSoWhite wasn’t—isn’t—only about a stuffy institution failing to recognize work by people of color. Pushing the industry to allow Black filmmakers and actors to tell more substantial stories through high-profile work is a crucial step toward remedying the systematic issues at the heart of this controversy. But it’s not the only step. To change Hollywood, it’s important not only to look forward but to look back.

We must recognize that even with the financial and systemic odds stacked against them, Black filmmakers have long been creating great and riveting stories on screen. The academy’s failure may have inspired a memorable hashtag, but that failure is deeply linked to the way nearly all movie fans remember cinematic history. In our never-ending conversation—or argument—about which films deserve to be remembered, which films are cultural touchstones, which films defined and advanced the art form, we habitually overlook stories by and about Black people. Consider the many widely regarded lists of the “best films”: the prestigious Sight & Sound once-a-decade critics’ poll, the American Film Institute’s eight different 100 Years … lists, or Richard Corliss’ top 100 for Time. Total number of Black-directed films among the 1,000 movies on those lists? Two. As Buggin’ Out (Do the Right Thing, No. 96 on AFI’s 2007 list) would ask, “How come there ain’t no brothers up on the wall?”

These lists are important: They affect the types of movies that self-proclaimed cinephiles and casual viewers alike seek out and watch, and they help define our ideas about whose perspectives matter. The exclusion of Blackness from these film canons shapes our expectations about what constitutes greatness in film. And it helps cement the expectation that whiteness is somehow as “universal” in art as so many believe it to be in life.

It’s time to fight the canons that be. Slate asked more than 20 prominent filmmakers, critics, and scholars—including Ava DuVernay, Robert Townsend, Charles Burnett, Gina Prince-Bythewood, Wesley Morris, and Henry Louis Gates Jr.—for their favorite movies by filmmakers of color and used their picks to shape our list of the 50 greatest films by Black directors. (That restriction excluded many beloved movies about Black people, like Carmen Jones, A Raisin in the Sun, The Wiz, and Coming to America. Many of those films are great and integral to understanding Black film history—but this list is about the power of Black people telling their stories.) Our goal is to change the way readers think about the history of movies—and to keep the conversation about Black storytelling going long after the #OscarsSoWhite fury has dissipated. That controversy and the immediate responses to it—including the Academy’s rule changes—only carry us as far as the Dolby Theatre. They don’t change the playing field.

Despite everything, Black filmmakers have produced art on screen that is just as daring, original, influential, and essential as the heralded works of Welles, Coppola, Antonioni, Kurosawa, and other non-Black directors. Films like Daughters of the Dust, Killer of Sheep, Tongues Untied, and Fruitvale Station deserve to be considered alongside the artistic masterpieces of the past century in cinema. But you should also consider this list an argument for a broader notion of what constitutes a “great” film—after all, many of the movies that have shaped Black culture (and the broader American culture) don’t easily fit into the templates of auteurist, art house, or studio “quality” favored by the typical list-makers. Genre work, micro-budget indies, underground documentaries, comedies starring rappers—it was eye-opening to see what movies our panel of experts chose. (And didn’t choose.) The result: Slate’s Black Film Canon. Read, watch our video supercut, stream an unfamiliar movie or two, argue, and recognize the names on our list for the great filmmakers they are.

Within Our Gates (Oscar Micheaux, 1920)

If we lived in a truly just world, Within Our Gates would have snuffed out the racist influence of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation early on, saving us from years of harmful stereotypes (and the revival of the KKK). We don’t, and it didn’t—but Oscar Micheaux’s cinematic challenge to the celebrated white filmmaker has earned its own place in history as agitprop at its most necessary. Through its mixed-race protagonist Sylvia (Evelyn Preer), the film starkly portrays lynching and the attempted rape of a Black woman by a white man at a time when such crimes were everyday fears for Black people. It’s daring, dangerous filmmaking, and a must-see for anyone attempting to unpack the history of racial conflict in America.

“A controversial, lightning rod film by one of the first pioneering Black filmmakers.” —Stephane Dunn

“One of the earliest repudiations of D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation, Within Our Gates examines Black striving, and American racial violence, through a black lens.” —Paula Massood

The Blood of Jesus (Spencer Williams, 1941)

If modern audiences know Spencer Williams’ legacy at all, it’s as Andy in the much-maligned Amos ’n’ Andy television show. But he was also a talented filmmaker in his own right, and one of the few Black directors of the 1940s. The Blood of Jesus is a morality tale that draws from the deep roots of the Black church: Williams plays Ras, a good-hearted “sinner” who accidentally shoots his god-fearing wife, Martha (Cathryn Caviness), after dropping his rifle on the floor. Martha’s spirit is brought to a crossroads, and the story follows her temptations by both the devil and an angel. In the years since its release, it’s been highly praised as an exemplary work in the race film tradition, and as a historical account of Black Southern Baptist culture, it remains invaluable today.

“Spencer Williams was a brilliant director—Spike Lee before Spike Lee. In The Blood of Jesus he masterfully employed a sophisticated blend of on-location realism, fresh and improvised performances from non-professional actors, and inventive fantasy elements, including footage from the 1911 Italian film L’Inferno.” —Henry Louis Gates

Black Girl (Ousmane Sembène, 1966)

Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop) is a Senegalese woman, dreaming of a better, more exciting life, who follows her rich French employers back to Europe to continue her work as their nanny. Her dreams are soon dashed, however, when the couple, no longer able to afford the vast staff they employed back in Dakar, forces her into full-time servitude. Ousmane Sembène plaintively captures a working-class immigrant experience while harshly critiquing Western perceptions of African culture. Even before the film’s 50th anniversary inspired a series of fresh and fascinating critical perspectives, Black Girl was known as the first masterpiece of the father of African cinema.

“Black Girl has the simplicity and freshness—not to mention the crisp black-and-white cinematography—of an early French New Wave film. But it’s an unsparing dissection of postcolonial race relations, with an ending stark enough to make Jules and Jim’s tragic conclusion seem like a fairy-tale happy-ever-after.” —Dana Stevens

The Learning Tree (Gordon Parks, 1969)

In rural 1920s Kansas, teenager Newt Winger (Kyle Johnson) learns to deal with everyday racial prejudice, be it unsettling interactions with law enforcement, his teachers, or more generally, the white gaze. The Learning Tree holds the distinction of being the first Hollywood studio film directed by a Black filmmaker, but it’s not merely pioneering: It’s an influential, emotionally arresting drama that gets at the heart of the difficult adolescent experience. Adapted from renowned Life photographer turned director Gordon Parks’ semi-autobiographical novel, this quiet film packs a powerful message.

“It’s sometimes forgotten in the shadow of Parks’ Shaft, but it’s an even bigger, more beautiful achievement.” —Odie Henderson

Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song (Melvin Van Peebles, 1971)

Viewed through modern eyes, Melvin Van Peebles’ film (often credited as the starting point for the Blaxploitation genre) is shocking. Sweetback opens with a young boy (played by Melvin’s son Mario) losing his virginity to a prostitute in the brothel where he’s been taken in; given the name Sweetback for his natural endowment, he grows up to become an exhibitionist in a whorehouse. One night, he’s falsely arrested for the murder of another Black man but manages to escape from his handcuffs and beat the LAPD officers unconscious. As Sweetback flees from the law, Van Peebles spins a narrative of Black consciousness and rebellion that is both troubling and fascinating.

Shaft (Gordon Parks, 1971)

Gordon Parks’ shaggy detective story is hardly perfect. Though it’s a thoroughly satisfying B-movie, it can feel a bit slow to modern sensibilities. But from Isaac Hayes’ iconic Oscar-winning theme song to its fashion, Shaft was a sensation. Richard Roundtree was so compelling as a Black action hero (in a time when Black action heroes were virtually nonexistent) that he instantly became the leading man every man wanted to be and every woman wanted to be with. The film was an enormous hit and is credited by many with saving MGM from bankruptcy. Everything about Shaft was cool, and all anyone wanted to talk about in the summer of 1971 was that bad mother—.

“The first Black detective thriller helmed by a Black director. It paved the way for all the other Black action heroes to follow.” —Ernest Dickerson

Super Fly (Gordon Parks Jr., 1972)

Super Fly superficially resembles many of the terrible Blaxploitation films of its era. It’s got a stereotypical pimp protagonist (Priest, played by Ron O’Neal), excessive and unnecessary female nudity, and “jive” dialogue. But compared with those other films (many of them helmed by white directors), this action-adventure from Gordon Parks Jr. (son of Shaft director Gordon Parks) has higher thematic aspirations. Even as he revels in the drug-fueled gangster lifestyle, Priest’s ultimate goal is to leave the game for good and triumph over that most daunting of adversaries for Black Americans: the Man.

“Of all the films of the Blaxploitation era Super Fly resonated the strongest. With all its flaws there is still a raw ghetto beauty.” —Carl Franklin

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (Ivan Dixon, 1973)

Under political pressure to integrate, the CIA undertakes a search for its first Black case officer. The last man standing after a rigorous training program is smart, calculating Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook), who’s immediately placed behind a desk as a token. But the joke’s on the CIA: Black nationalist Freeman has planned all along to learn the CIA’s tactics and use them to recruit young Black men in cities across America in order to spark a revolution. Ivan Dixon’s scathing satire, based on Sam Greenlee’s novel of the same name, is vital, important filmmaking that is also grimly funny and thrilling to watch.

“I remember sitting in the theater, and thinking, ‘Oh my God, this is not a regular movie.’ I left and told everybody in the neighborhood: It’s not bullshit man, it’s real, it’s real. The next day it was gone out of all the theaters.” —Robert Townsend

“Many have long speculated that the film was pulled by law enforcement entities due to its overtly political message.” —Todd Boyd

Touki Bouki (Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973)

A sensation upon its screening at Cannes, Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty’s road movie follows two young lovers as they dream of escape to Paris—or, truly, of returning from Paris in triumph for all their friends in Dakar to see. A jazzy, freewheeling blend of traditional African cinema and French New Wave, Touki Bouki follows these two frustrated souls (Magaye Niang and Mareme Niang) as they turn to petty crime to fund their high hopes. Mambéty won the International Critics Prize at Cannes but would make only one more feature before his death in 1998. More than 40 years on, Touki Bouki is still slyly entertaining, a Senegalese Bonnie and Clyde shot through with good humor and frustrated promise.

“If Ousmane Sembène was Lester Young, Djibril Diop Mambéty would be John Coltrane. Mambéty followed Sembène’s politically driven approach to cinema with a strong influence from the French New Wave, but so powerfully African.” —Floyd Webb

Cooley High (Michael Schultz, 1975)

When it came out, Cooley High was widely compared to another 1960s-set story of teenage boys coming of age, American Graffiti, but with the benefit of hindsight, Cooley is the better film, more clear-eyed and honest in its view of adolescence. (Also, its Motown soundtrack has aged better than the doo-wop and early rock of Graffiti’s.) Written by Good Times co-creator Eric Monte, Cooley High follows teenage friends from Chicago’s Cabrini-Green projects as they cruise, skip class, ball, flirt, fight, and get in just enough trouble. Featuring Glynn Turman, Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs, and Garrett Morris, the movie’s low-key good humor influenced a kid from the projects who made his very first film appearance in Cooley as a basketball player: Robert Townsend.

“I just remember that last scene with Glynn Turman at the grave site, and I just remember how beautiful that monologue was, and how he delivered it, and how much heart it had, and it reminded me of my friends. It was like a slice of life.” —Robert Townsend

“The way we were (at least I was) growing up a Black teenager in the 1960s.” —Ernest Dickerson

Car Wash (Michael Schultz, 1976)

You definitely know quite a few of the songs from the hit Grammy-winning soundtrack. But don’t let that overshadow the legacy of the film itself: Michael Schultz’s day-in-the-life ensemble piece deserves to be revisited and remembered. The colorful cast of characters populating this L.A. car wash—including self-serious Black militant Abdullah (Bill Duke) and hard-working ex-con Lonnie (Ivan Dixon)—is lovingly detailed and multifaceted, their many stories brought together through clever staging and sonic cues. The humor is balanced between the goofy and sharply satirical (witness Richard Pryor’s brief cameo as a phony evangelist). Yet for all its comedic touches, Car Wash aims for something deeper—a humanistic look at the struggles of working-class people of color in the ’70s—and delivers in its dramatic finale.

“Comedy often doesn’t get its due when great films are being discussed, but Car Wash is doing something really special, honest, and hilarious.” —Kevin Avery

“A masterpiece on par with Altman’s Nashville that has been unjustly relegated to cult comedy status.” —Keith Corson

Killer of Sheep (Charles Burnett, 1978)

Charles Burnett shot his debut feature during a year’s worth of weekends in Watts, Los Angeles, but Killer of Sheep went unreleased for decades due to music-clearance issues, despite being recognized almost immediately as a masterpiece. (It was even inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1990.) Decades later, it still feels revolutionary—a ghetto movie with the soul of a neorealist classic, deeply concerned not just with issues of Black manhood but of personhood. Few films have ever asked the question at the center of Killer of Sheep with such passion and heart: What does it mean to be human in a world designed to deprive you of that humanity?

“80 minutes of realist magic. Hard, soft, dreamt, awake, happy, dolorous. Jean Renoir, Vittorio De Sica, Satyajit Ray, this.” —Wesley Morris

“Killer of Sheep’s stark representation of Black urban life and the machinery of systemic racialized poverty on a Black family and community is, in a word, unforgettable.” —Stephane Dunn

Ashes and Embers (Haile Gerima, 1982)

Haile Gerima’s drama is hardly as well-known or celebrated as other films of its era about Vietnam vets. (It went unreleased for decades before Ava DuVernay’s film distribution company Array restored it and brought it to Netflix earlier this year.) But Ashes and Embers is haunting in its depiction of the horrors of fighting the war, and of Black vets’ despair at returning to an equally bleak existence in the United States. By focusing on both disaffected vet Ned Charles (John Anderson) and his resilient grandmother (Evelyn A. Blackwell), Ashes and Embers deftly confronts the racially charged political climate of Jim Crow and the late ’70s.

Losing Ground (Kathleen Collins, 1982)

Kathleen Collins was a film professor at City College of New York when she directed her only movie, a no-budget charmer that mixes lighthearted philosophical inquiry with serious whimsy. The film never saw release; if it had, it would have been the first American feature directed by a Black woman ever to play in theaters. Instead, it was a missed opportunity. Thankfully, in 2015 the tiny distributor Milestone Films got it into theaters (and out on DVD). Uncommonly for its era, it’s relatively unconcerned with racial politics but instead wrapped up in affairs of the heart and affaires d’art, as its main characters—an artist, a filmmaker, a dancer, and a philosophy professor—dance together on film and on canvas, in classrooms and in summer homes.

“Lovingly, fancifully made, never released, and therefore barely seen, Collins’ romantic thingamabob is powerfully, strangely alive. Collins died in 1988. This was her only movie. So, in its way: a tragedy.” —Wesley Morris

Sugar Cane Alley (Euzhan Palcy, 1983)

Euzhan Palcy’s debut feature won the César for best first film in 1984, a signal moment in the French film industry, which has long struggled with the legacy of colonialism and the reality of people of color within the nation’s borders. Set in a midcentury sugar cane plantation in the French West Indies, this beautifully made drama casts its view backward and forward, as its clever young hero José excels in school and dreams of the future while also being taught about the days of slavery by an elderly neighbor. Palcy—born in Martinique, educated in France, mentored by François Truffaut—adapted Joseph Zobel’s novel La Rue Cases-Nègres but imbued the film with her own love and concern for the island she called home.

“This beautifully directed explication of the effect of French colonialism on the native people in a 1930s shantytown in Martinique is a visually vivid narrative that brilliantly unfolds the life of its young protagonist.” —Stephane Dunn

Hollywood Shuffle (Robert Townsend, 1987)

Robert Townsend directed, starred in, and co-wrote (with Keenen Ivory Wayans) this daring, scathing critique of Black representation in Hollywood. The 2½-year production process drained Townsend’s bank account, but the result—imaginative, hard-hitting sketches like “Black Acting School” and “Attack of the Street Pimps”—is a classic of industry satire. And, sadly, it might be even more relevant today than it was when Townsend made it.

“A satire of racism in Hollywood that’s also a tragedy that still doubles as a documentary. You laugh, but it’s a heavy, complicated, sad kind of laughter.” —Wesley Morris

“#OscarsSoWhite and also #RobertTownsend SoAheadOfHisTime!” —W. Kamau Bell

Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

“Wake up!” HATE and LOVE. The guy in the Larry Bird T-shirt. “That’s the truth, Ruth.” The ethnic-slur montage. “Thank God for the right nipple.” Roll call. “Stay Black.” TAWANA TOLD THE TRUTH. “How come there ain’t no brothas on the wall?” The fire hydrant and the convertible. “Extra cheese is two dollars.” The trash can. “Fight the Power.” We didn’t rank the movies on this list because figuring out Nos. 2 through 50 would be too difficult. But there was never any question what movie was No. 1.

“Raw, vocal, in your face, aggressive, brave, necessary.” —Gina Prince-Bythewood

“An anthem, a love song, a hymn, and a dirge. Haiku and soliloquy. In Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee offers a visual and sonic equivalent for every kind of poetry, trained on the theme of love and hate as tools for/obstacles to survival.” —Steven Boone

Tongues Untied (Marlon Riggs, 1989)

While he was making this raw, disjunctive, multivocal valentine to Black gay male subculture, filmmaker and activist Marlon Riggs learned he was HIV-positive in an era when that diagnosis was a death sentence. Riggs would live long enough to make a few more gripping nonfiction films, but this lyrical and sexually frank first-person video essay—brandished by conservative demagogue Pat Robertson as an example of the “pornographic and blasphemous” art PBS was using tax dollars to help fund—remains a great testament not only to Riggs’ talent but to an entire generation lost.

“‘Black men loving Black men is a revolutionary act,’ reads a banner carried by protesters in Tongues Untied. Watching this eloquent and fierce tribute to the world Riggs loved and was about to leave, you realize both how far that revolution has come and what a long way it still has to go.” —Dana Stevens

House Party (Reginald Hudlin, 1990)

In Reginald Hudlin’s hit comedy, Black teenage movie characters were finally allowed to be as freewheeling and mischievous—without things ever getting too heavy—as their white counterparts had been in high school romps for decades. Rap-comic duo Kid ’n Play (Christopher Reid and Christopher Martin) are best friends who just want to throw a wild house party while Play’s parents are out of town. Of course many zany characters and obstacles stand in their way. Hudlin’s film is zippy and light, bursting with youthful energy and an iconic dance sequence. And its two prizes at Sundance began to shift the industry’s view of what “indie film” can be.

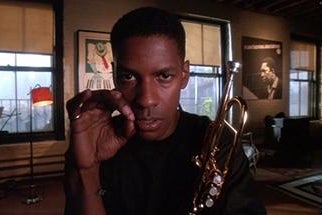

Mo’ Better Blues (Spike Lee, 1990)

Spike Lee declared his follow-up to Do the Right Thing was a corrective to portraits of self-destructive, tortured jazz geniuses like Clint Eastwood’s Bird. But this stylish film is better understood as a satisfying old-fashioned love triangle, with an understated Denzel Washington performance at its center. But it’s also a key step in Lee’s development as a director. The sequence in which Washington, as trumpeter Bleek Gilliam, argues with both women in his life—having called each of them by the wrong name in bed—is a miniseminar in slow-burning comedy created through camera positioning and editing. And the movie’s often-ostentatious craft—the luxe interiors of Bleek’s jazz club, Giant’s flashy threads, the carefully choreographed musical numbers—point the way to the bigger canvas on which Spike was about to paint. Mo’ Better Blues is the bridge between the ambitious young director who made a scruffy masterpiece about Bed-Stuy and the confident auteur who was about to shoot Malcolm X.

To Sleep With Anger (Charles Burnett, 1990)

When Danny Glover’s Harry Mention first shows up at the door of a middle-class Black family in South Central L.A., he’s welcomed as an old friend and a link to their Southern roots. But as Harry’s drop-in visit turns into an extended stay, this enigmatic and volatile trickster begins to exert a malevolent, near-demonic power over the comfortably aspirational clan, opening up socioeconomic and generational fault lines and bringing long-repressed conflicts to a boil. Required viewing for anyone who wants to understand how America has changed in the past 100 years, Charles Burnett’s comic masterpiece is both a precise vivisection of Black upward mobility and a barbed eulogy for the sharecropper life the Great Migrators left behind.

“A Black family drama laced with homespun mystery and magic realism.” —Ernest Dickerson

“Half folk parable, half social-realist domestic drama, To Sleep With Anger still casts an uncannily discomfiting spell two and a half decades after its release. Like the slippery-but-seductive houseguest played with infinite nuance by a never-better Danny Glover, it’s a movie whose ambiguity only adds to its richness.” —Dana Stevens

Boyz n the Hood (John Singleton, 1991)

The quintessential “hood” movie that sparked a flurry of ’90s imitators, John Singleton’s debut made him, at 24, the youngest nominee ever for the Best Director Oscar. He didn’t win (and his film wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture), but 25 years later, Boyz n the Hood still stands among the best films of the decade. Coaxing inspiring dramatic performances from then-newcomers Cuba Gooding Jr., Morris Chestnut, and Ice Cube (as well as powerful turns from seasoned pros Angela Bassett and Laurence Fishburne), Singleton captured a very particular cultural moment and uncovered the anger, despair, and even hope of an urban Black America that had been largely ignored by the rest of the nation.

“It made an impact and gave voice to struggling youths.” —Charles Burnett

Daughters of the Dust (Julie Dash, 1991)

It’s difficult to imagine that it took until 1992 for a film directed by a Black woman even to see movie screens in the U.S. Julie Dash’s meditation on womanhood in a Gullah-Geechee community off the coast of South Carolina would deserve a place on any list just for breaking that barrier. But Daughters of the Dust is a remarkable film: a lyrical dream of rural life that’s plainspoken about its troubles. And it’s also achingly gorgeous—even before you consider the shoestring on which it was made, by Dash and a mostly female crew in the wake of Hurricane Hugo. Funded by PBS’s American Playhouse, Daughters won awards at Sundance and played well in theaters across the country; nonetheless, Dash has noted, “since coming off the Sundance stage, I have never gotten a motion-picture deal.” Maybe this fall’s rerelease of Daughters in theaters will help.

“Dash insisted on making a migration film that would rely on the vibrancy of images, the richness of Gullah cultural rituals and its African rooted ancestral signification, finally, but not the least, the beauty of Black women’s voices, bodies, and stories.” —Stephane Dunn

“It has and will continue to have an impact on developing filmmakers, especially women filmmakers.” —Charles Burnett

Juice (Ernest Dickerson , 1992)

After a prolific decade making his name as an exceptional cinematographer—he shot Spike Lee’s first three films on this list—Ernest Dickerson turned to directing with this coming-of-age classic. Q (Omar Epps), Bishop (Tupac Shakur), Raheem (Khalil Kain), and Steel (Jermaine Hopkins) are best friends living in Harlem whose lives get turned upside down after a bodega robbery results in murder. Wild-card Bishop gets a rush from his act and quickly becomes a threat to everyone around him, including his best friends. A dark, excellently crafted thriller about the dangers of unfiltered machismo.

Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (Leslie Harris, 1992)

Leslie Harris quit her job at an advertising agency to write and direct this spirited portrait of a 17-year-old girl from Brooklyn who dreams of going places. “I was just tired of seeing the way Black women were depicted, as wives or mothers or girlfriends or appendages,” Harris told the New York Times from Sundance, where her film won a Special Jury Prize on the way to a Miramax release. Almost 25 years later the film, with its early-’90s fashion and its fourth-wall–breaking smartass of a heroine, feels very of its time. But the story it tells, of an ambitious young woman making a place for herself in the world, will ring true to viewers of any era.

Malcolm X (Spike Lee, 1992)

The story of the life of the polarizing civil rights leader passed through many hands for more than 20 years, settling, in 1990, in those of distinguished director Norman Jewison, who brought on board his star from A Soldier’s Story, Denzel Washington, to play the lead. But Spike Lee and others famously protested that this was a Black story to tell, and Jewison soon bowed out, replaced by Warner Bros. with Lee himself. We should all be forever grateful that Lee, in the prime of his career, got to put his stamp on Malcolm X. Nearly every piece of it works, from Ruth E. Carter’s explosive, Oscar-nominated costume design to Lee’s efficient, passionate screenplay to the icon-making turn of Washington as “Detroit Red” himself. Together, Lee and Washington captured Malcolm’s voice and created a polarizing, must-see, once-in-a-generation cinematic event.

“A movie that every Black person should see.” —Carl Franklin

Sankofa (Haile Gerima, 1993)

The sankofa symbol has been historically linked to a West African proverb centered on the notion of returning to the past to learn from it. Haile Gerima’s sweeping film builds on this important lesson. While in the midst of a photoshoot on the Cape Coast Castle in Ghana (once a major hub for the Atlantic slave trade), Black American model Mona (Oyafunmike Ogunlano) is transported back in time to a slave plantation in the American South. Gerima deftly unpacks the many layers of systemic and emotional oppression at work among his fully realized ensemble. By the end, Mona has returned to the present with a new understanding of the ways oppression reverberates through history—and so have we.

“Hollywood might not have heard of this, but in the Black community it is known. This film affects everyone who watches it.” —Charles Burnett

“Perhaps one of the best things done on slavery.” —Ed Guerrero

Crooklyn (Spike Lee, 1994)

After the Sturm und Drang of Malcolm X, Spike Lee went personal for this jazzy, self-indulgent family curio, co-written with his siblings and based on their own childhood in striving middle-class 1970s Brooklyn. Modest in scale, Crooklyn contains some of the most vivid, enjoyable, affectionate scenes of Lee’s career, as well as finely tuned performances from Delroy Lindo (as the family’s distracted jazz-composer father) and Alfre Woodard (as its combustible mother). The film’s remarkable second half evolves into a coming-of-age story for young Troy (Zelda Harris), the stand-in for Spike’s sister and co-writer Joie Lee, as she navigates young womanhood in a trip down South and upon her return to a measurably sadder New York. It’s the Spike movie you might have skipped, but it’s the one that will make you love him all the more.

I Like It Like That (Darnell Martin, 1994)

The first film by a Black American woman to debut at Cannes, I Like It Like That is a lively, funny drama about a Puerto Rican mom of three just barely out of girlhood herself whose philandering husband lands in jail. As Lisette, Lauren Vélez shouts, dances, bluffs, and charms her way through hardship and into a job with a record executive; the movie never loses its scrappy good humor while remaining clear-eyed about the barriers to security and happiness facing residents of Lisette’s Bronx barrio. As an Un Certain Regard entry in Cannes, the film charmed audiences but was overshadowed by Pulp Fiction; back home, its studio had trouble marketing a movie with such rambunctious indie-flavored spirit. But it’s an adventuresome film about characters who too often see themselves relegated to the sidelines, told with charm and visual flair by a young filmmaker with as much verve as her heroine.

Devil in a Blue Dress (Carl Franklin, 1995)

Carl Franklin’s 1948-set L.A. murder mystery, adapted from the first of Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins novels, is sexy, funny, and exciting. It stars Denzel Washington at his charismatic peak as reluctant detective Easy and gave Don Cheadle the role of his young career as his volatile buddy Mouse. It should have made $100 million, garnered all the Oscar nominations that L.A. Confidential would land two years later, and launched a profitable series of Easy Rawlins movies you could watch on Starz today. Instead, Devil underperformed, the series fizzled out, and only this nearly perfect noir remains as the lone evidence of what could have been.

Friday (F. Gary Gray, 1995)

A day in the life of South Central best friends Craig (Ice Cube) and Smokey (Chris Tucker), who find themselves entangled in the bizarre (and sometimes violent) misadventures of their off-kilter neighbors. Friday is dense with joke after joke after joke, and its batting average of instantly quotable moments is wildly impressive. F. Gary Gray and his endearing cast showcase specific, well-rendered characters within a broadly comic, shaggy plot.

“Friday led to a ton of other Black comedies. It created a new star in Chris Tucker. And it began the turn of Ice Cube into a family-friendly PG-rated dad. And absolutely nobody saw that coming.” —W. Kamau Bell

“For him to take a movie that’s just set in the neighborhood and add so many layers and dimensions to it—and with comedy. That’s not an easy task. I just thought it was masterful.” —Robert Townsend

Waiting to Exhale (Forest Whitaker, 1995)

It would be very easy to deem this Terry McMillan adaptation, in which Black women fail at love in every way imaginable, a kitschy chick flick at best, a disturbing, stereotypical portrayal of the angry, desperate Black woman at worst. But it’s in teetering dangerously close to both those descriptors that Waiting to Exhale finds its groove, attempting to delve deep into the psyche of its female leads and understand them. Bernadine tailspins into rage when her husband leaves her for a white woman (famously setting her car on fire); Robin (Lela Rochon) dates one dud after another; Vannah (Whitney Houston) falls in love with a married man; Gloria (Loretta Devine) finds love with her neighbor after learning her ex-husband is gay. It’s overwrought, obvious, and ultimately engrossing—a potent Douglas Sirk tale for the ’90s woman.

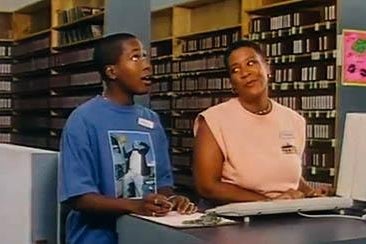

The Watermelon Woman (Cheryl Dunye, 1996)

Writer-director Cheryl Dunye plays Cheryl, a movie nerd toiling at a Philadelphia video store who becomes entranced by a Black actress she sees popping up in mammy roles in movies from the ‘30s and ’40s, credited only as the Watermelon Woman. She decides to learn more about this mysterious actress and make a documentary about her, interviewing various film researchers and locals with personal connections. The resulting fictional documentary is both funny and thoughtful, presenting the oft-marginalized (women of color, lesbians) in rich detail while grappling with the uncovering and retelling of history.

“A highly self-conscious mock documentary/essay film that parallels a historical plotline with the director’s own journey of self-discovery as a Black lesbian filmmaker trying to determine her vision.” —Paula Massood

Eve’s Bayou (Kasi Lemmons, 1997)

Actress-turned-filmmaker Kasi Lemmons opens her directorial debut with an arresting voice-over: “The summer I killed my father, I was 10 years old.” A mystical, Southern Gothic tale of unreliable memory and familial shame, Eve’s Bayou surveys a collection of rich characters within a wealthy Black community in Louisiana. The cast is excellent: Young Jurnee Smollett and Meagan Good evoke the film’s grand theme of sisterhood as Eve and Cisely while Samuel L. Jackson, Lynn Whitfield, and Debbi Morgan dazzle as the complex, troubled adults in their lives. Roger Ebert led the critical charge for the film on its release, comparing Lemmons’ portraiture of family secrets to “Bergman, Chekhov, and Eugene O’Neill.”

“It changed the game for Black independent film. Incredibly beautiful on every level. Showed incredible craft, announced a new voice.” —Gina Prince-Bythewood

“A gorgeous slice of Southern Gothic, featuring supernatural elements, strong female characters and a sensual, subdued Sam Jackson. Striking in its originality and unapologetic in its Blackness.” —Odie Henderson

Love and Basketball (Gina Prince-Bythewood, 2000)

“I wanted to make a real love story with Black people,” Gina Prince-Bythewood told Slate about Love and Basketball. “Not a romantic comedy, but the kind that wrecks you and builds you back up.” In her feature debut, she wrecked us, then built us back up with the story of Monica and Quincy (Sanaa Lathan and Omar Epps), childhood friends, adolescent rivals, and on-again/off-again lovers. Prince-Bythewood pulls wonderful performances from her stars and crafts the all-too-rare picture of what it’s like to be a woman in the sports world. The movie shares Monica and Quincy’s passion for each other, and for the game they love.

“She painted on a romantic canvas that we normally don’t see. We don’t get that many love stories, and she gave us a love story that made us believe in love again.” —Robert Townsend

25th Hour (Spike Lee, 2002)

Monty (Ed Norton) has 24 hours before he heads to prison for seven years after getting caught dealing drugs. Spike Lee’s melancholic tale of loss, regret, anger, and fear chronicles that final day as Monty confronts his relationships with his girlfriend (Rosario Dawson) and old high school buddies (Philip Seymour Hoffman and Barry Pepper). And he does this all against the background of a New York City still fresh from the pain and destruction of 9/11—creating a powerful drama that feels oddly like the definitive story of that time.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (Darnell Martin, 2005)

Let us not count the ways that Darnell Martin’s film—produced for TV by Oprah Winfrey and starring Halle Berry—diverges from Zora Neale Hurston’s beloved 1937 novel. Does the screenplay (by Suzan-Lori Parks, Misan Sagay, and Bobby Smith Jr.) elide Hurston’s racial-sociological concerns, transforming the rich language of her novel into a potboiler about a good woman, big trouble, hot love, and good hair? You bet. But oh, does that pot runneth over. Halle Berry weeps, moans, laughs, and stares dreamily at the sky as Janie, who makes her way through a series of attractive men while building and tearing down her fortunes again and again. The film’s final third, when her true love Tea Cake (Michael Ealy) survives a hurricane only to succumb to rabies from a mad dog’s bite, is melodrama at its most cathartic. The novel was both art and history—a stubborn, nearly lost-to-time book that will be studied and loved for generations. The movie is overblown, blowsy, and completely delicious.

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (Spike Lee, 2006)

Spike Lee’s narrative filmography is polarizing, even among his defenders, but few disagree that his documentaries are masterful. This four-part essay deconstructing Hurricane Katrina, released almost exactly a year after the storm, is his crowning achievement. Shooting this sobering indictment of a failed government, Lee secures brutally honest interviews from almost every major player involved, from Gov. Kathleen Blanco and now-disgraced Mayor Ray Nagin to Soledad O’Brien, Sean Penn, and Kanye West. Most affecting of all are the nonfamous, the locals hardest hit by the devastation—all of them telling heartbreaking stories of survival that will serve as a searing historical record for all time.

“Lee’s quality can be maddeningly inconsistent, but when his insouciance and his outrage meet a rich, ripe target, as they do in post-Katrina New Orleans, his filmmaking becomes its own justice system.” —Wesley Morris

Medicine for Melancholy (Barry Jenkins, 2008)

Is Barry Jenkins’ two-handed romantic drama a Black Before Sunrise? It does follow a young couple who’ve just met through a day together as they explore both a city (in this case San Francisco) and their mutual attraction. But where Richard Linklater’s lovers are concerned with airy Big Questions, sometimes to the movie’s detriment, Medicine for Melancholy’s Micah and Jo’ debate specifics: the role of Black men and women in a city where people of color are being erased, and an indie subculture that respects Blackness without actually finding any place for it in its ranks. The result is a smart and subtle generational portrait that also functions as a touching love story—a promising debut for a director whose second film will be the first produced by top-shelf boutique distributor A24.

“A poignant film dealing with self-definition and the shifting nature of Black communities in the face of gentrification. Contemporary San Francisco captured in a style reminiscent of Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7.” —Keith Corson

Night Catches Us (Tanya Hamilton, 2010)

Perhaps the definitive cinematic portrait of the woozy aftermath of countercultural militancy, Tanya Hamilton’s 1976-set film brings together two former Black Panthers: Patricia (Kerry Washington), now a respected lawyer and community organizer, and Marcus (Anthony Mackie), on the run for years. Captured just on the cusp of stardom, the two leads share a rich, slow-burning chemistry, and Hamilton’s bicentennial-era Philly sits uneasily between revolution and giving up. Bonus: a score from the Roots.

Pariah (Dee Rees, 2011)

A lovely film about a young lesbian’s coming of age in Brooklyn, Dee Rees’ Pariah is both a tender family drama and an exuberant story of self-discovery. The 17-year-old Alike, played by the wonderful Adepero Oduye, yearns for her first sexual experience; her straight-laced parents (Charles Parnell and Kim Wayans) struggle between their love for their daughter and their misunderstanding and mistrust of the person they see her becoming. Shot by the great cinematographer Bradford Young, Pariah explores the evolution of its heroine and the streets and houses of her Fort Greene neighborhood with curiosity, warmth, and empathy.

“Dee Rees course corrects the invisibility of Black women in the LGBTQ community.” —ReBecca Theodore-Vachon

“Just when you think every coming-out–as–coming-of-age story has been told, along comes Pariah. Adepero Oduye is incandescent as she’s forced to code-switch between the ladylike conduct expected by her churchgoing parents and the mystifying rituals of the gay nightclub she frequents to try on alternate identities.” —Dana Stevens

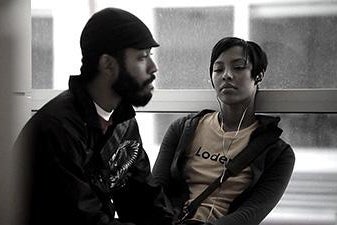

Middle of Nowhere (Ava DuVernay, 2012)

Ava DuVernay’s second feature tells the story of Ruby (the enchanting Emayatzy Corinealdi), a nurse who finds her life and dreams in limbo while she waits for her husband (Omari Hardwick) to serve out a prison sentence. Ruby drops out of medical school and spends years commuting back and forth to the faraway prison where he’s incarcerated. In the midst of her wearying self-sacrifice, she develops a tentative relationship with Brian (David Oyelowo), a kind bus driver. DuVernay gets deep inside the head and heart of her protagonist and surrounds her with supporting characters who are equally rich and layered—a skill she would demonstrate on a larger scale with the film that would introduce her to the mainstream, Selma.

“DuVernay takes a sledgehammer to the Strong Black Woman trope by illuminating the isolation experienced by Black women living in the margins.” —ReBecca Theodore-Vachon

“Ava DuVernay tells stories that tap into what audiences have been longing for.” —Charles Burnett

12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013)

In the most brutal and visceral account of slavery ever depicted on film, Steve McQueen adapts the slave narrative memoir of Solomon Northup, a free Black man who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841. McQueen’s direction is unrelenting and assured; his cast, led by Chiwetel Ejiofor’s powerful performance as Northup, is exceptional. But the standout here is Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong’o, who brings to the tortured role of Patsey a bracing humanity. The film became the first by a Black director to win Best Picture at the Oscars.

“Brilliant and brave filmmaking. The first time I watched a film about when we were enslaved and felt it viscerally. It stayed with me for weeks on weeks.” —Gina Prince-Bythewood

Selma (Ava DuVernay, 2014)

Ava DuVernay’s film, nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars, isn’t a traditional biopic and doesn’t hit most of the expected story beats of King’s life. Instead DuVernay gives us a story about the protesters, the firebrands, the negotiators, and the rabble-rousers, all led by one of the century’s greatest heroes but far from united behind him. David Oyelowo’s pensive performance as King is the film’s center, but the scenes that stick in the memory place him at the center of a crowd: on the steps of the Capitol, or walking arm in arm with fellow activists across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. So DuVernay made something more than the definitive MLK movie we dreamed of. She made the definitive movie about the struggle, and about how change happens in fevered times: through hard, dedicated, dangerous work.

“Up until Selma there seemed to be only two ways to make a Martin Luther King film. 1) You make MLK a saint, which is boring, or 2) you make him a sinner, which will get you banned from all Black churches, Black barbecues, Black family reunions, and pickup basketball games. Ava DuVernay subverted those traps by making it about the movement.” —W. Kamau Bell

Belle (Amma Asante, 2014)

Amma Asante’s period piece inspired by the life of Dido Elizabeth Belle beautifully renders a perspective rarely portrayed on screen—that of the complex racial dynamics of 18th-century England. Gugu Mbatha-Raw is stunning as Belle, the daughter of an African slave from the West Indies and a British Royal Navy officer, who is taken in as a young child by her father’s uncle after her mother’s death. Raised as a free woman in London, she grows to understand how her mixed-race heritage complicates her place within the rigid social structures of her upper-class upbringing—and how she must assert herself in order to survive.

“Asante brilliantly weaves class, race, and gender in the rare Black historical narrative that centers on a woman as the heroine.” —ReBecca Theodore-Vachon

Fruitvale Station (Ryan Coogler, 2014)

For his feature debut, writer-director Ryan Coogler crafted a quiet, thoughtful drama about one young Black man, Oscar Grant, on the last day of his life. Shot in and around San Francisco and based on the real Oscar Grant III, who was shot and killed by a BART police officer in the early morning hours of New Year’s Day, Fruitvale Station is determinedly modest in its goals: Coogler seeks to understand Grant, not to use him as a symbol. The fact that the film was released between the deaths of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown is a testament to the importance and timeliness of Coogler’s artistic impulse. That the movie doesn’t collapse under the burden of all those real-world resonances is testament to his remarkable artistic control—and to the sharp and specific performance of Michael B. Jordan, who never lets the man he portrays fade into generalities.

Timbuktu (Abderrahmane Sissako, 2014)

Abderrahmane Sissako’s film was Mauritania’s first-ever Oscar nominee, but its heart is in Mali—specifically, the ancient cosmopolitan city of the title, overrun for a time in 2012 by Islamist fighters associated with al-Qaida. The residents of the city struggle to acclimate to their new rulers, who ban music, demand women wear headdresses, and punish citizens for playing football—all while loving hip-hop, flirting with the locals, and arguing about Lionel Messi. Sissako’s exposure of the jihadis’ hypocrisy can give Timbuktu a comic rhythm, but it’s sharply attuned to the tragedy of a community taken over by outsiders who care little for the city’s traditions, history, or people. The result is something of a fable, in which cruelly specific punishments are meted out by unjust rulers, but the young men gather nonetheless, in a remarkable sequence, for a game of ball-less football. The fighters were pushed from Timbuktu in 2013, but Sissako’s film remains a crucial portrayal of life as it’s lived by millions under the rule of “part-time terrorists” like ISIS, Boko Haram, and al-Shabab.

Creed (Ryan Coogler, 2015)

A Rocky sequel? What was Ryan Coogler thinking attaching himself to such a tired old franchise? But the Fruitvale Station filmmaker harnessed the studio resources afforded him by a commercial sure thing and made an electrifying, exciting, contemporary movie about a young Black man chasing his dream in the face of dismissal from the world at large. Michael B. Jordan’s focused performance is Creed’s heart and soul, of course, but its animating force is Coogler’s intelligent, searching camera—never more than in an instantly legendary fight sequence showing two rounds in a single take.

“A post-racial film that never even uses that stupid word. A #BlackLivesMatter film without the hashtag. It was a hit while Hollywood continually questions whether Black actors can headline big movies.” —W. Kamau Bell

Bessie (Dee Rees, 2015)

Biopics centered on Black women are few and far between. Dee Rees’ HBO film Bessie stands out as one of the best and most unabashedly honest portrayals of Black womanhood and sexuality put on screen. Rees garners excellent performances from Queen Latifah and Mo’Nique (as blues singers Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey), while skillfully exploring much of Smith’s short life, without her film feeling overstuffed or pedestrian. Bessie won four Emmys, including Outstanding Television Movie.

O.J.: Made in America (Ezra Edelman, 2016)

Ezra Edelman’s epic, expert 7½-hour ESPN documentary is about so much more than just the trial that captivated America throughout 1995. It’s about Los Angeles as the Black promised land—a promise that’s been broken again and again. It’s about the way O.J. Simpson positioned himself as the perfect antidote to the racial awakening of Black athletes that drove the culture in the 1970s, turning into an anodyne pitchman “beyond” race. It’s about the way the criminal justice system can devour Black men, and how American culture can devour celebrities. A mammoth undertaking larded with the kinds of jaw-dropping details that only come with years of dedicated research and investigative work, this is the definitive portrait of one of the defining events of late-20th-century American history, in all its tawdry glory.

Participants:

Kevin Avery: comedian and podcaster (Denzel Washington Is the Greatest Actor of All Time Period)

Ada M. Babineaux: co-founder of The Black Filmmakers Network

W. Kamau Bell: comedian and podcaster (Denzel Washington Is the Greatest Actor of All Time Period)

Steven Boone: film critic

Todd Boyd: film scholar

Charles Burnett: director (Killer of Sheep, To Sleep With Anger)

Keith Corson: film scholar

Julie Dash: director (Daughters of the Dust)

Ernest Dickerson: cinematographer (Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X) and director (Juice)

Stephane Dunn: film scholar

Ava DuVernay: director (Middle of Nowhere, Selma)

Carl Franklin: director (One False Move, Devil in a Blue Dress)

Henry Louis Gates Jr.: historian

Ed Guerrero: film scholar

Odie Henderson: film critic

Franklin Leonard: founder and CEO of the Black List

Paula Massood: film scholar

Wesley Morris: cultural critic

Gina Prince-Bythewood: director (Love & Basketball, Beyond the Lights)

Dana Stevens: Slate film critic

ReBecca Theodore-Vachon: film critic

Robert Townsend: director (Hollywood Shuffle, The Five Heartbeats)

Floyd Webb: producer (Daughters of the Dust) and director