This article supplements Slate’s Conspiracy Thrillers Movie Club. To learn more and to join, visit Slate.com/thrillers.

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation is not about Watergate. It was conceived in the late 1960s and rooted in Coppola’s interest in advances in surveillance technology and the erosion of privacy. A first draft was completed in 1970 and the shooting script submitted in November 1972, months before the scandal erupted into the public consciousness. Nor was Coppola interested in making an overtly political film; on the contrary, he wanted it, he said, “to be something personal, not political, because somehow that is even more terrible to me.”

Nevertheless, with 11 months of postproduction, the film was not released until 1974, and it touched a nerve. Although it was indelibly influenced by Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up and the films of Alfred Hitchcock, as writer Mark Feeney has argued, no other film “is so atmospherically Nixonian.” Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) certainly has a lot of Nixon in him; wary of truth-telling, socially awkward, self-isolated, prone to obsession, and dysfunctionally paranoid, Harry is destroyed by his own tape recordings. But that is too easy, and it is a mistake to run too far with these parallels. Harry is really done in by the crushing weight of his own sense of guilt and responsibility. This was not one of Nixon’s problems. The Conversation resonates, then and now, not as an indictment of the disgraced president but as one small, brilliant Nixonian nightmare.

Coppola’s New Hollywood masterpiece is everything the ‘70s film aspired to be: personal, meticulous, riveting, profound. It is both a character study and a suspense film. To get caught up in the spellbinding mystery is to miss the point: The solution doesn’t matter; in fact, it is quite likely there are no solutions, conventionally speaking. With this inward turn Coppola parts company with both Hitchcock and Antonioni. About the souls of their protagonists we learn little, whereas The Conversation is about the character, not the crime. And what a character: Harry is neither a hero nor an antihero. Rather, as Walter Murch, the film’s sound editor (and crucial collaborator), points out, Coppola chose to focus the entire film on what in a standard thriller would be a minor character, the wiretapper, some guy who drops off the tapes and leaves. But The Conversation is about this essentially “anonymous person,” just as New Wave icon Claude Chabrol insisted that a film about “a hero of the resistance” is no more profound than one about “the barmaid who gets herself pregnant”; in fact, “the smaller the theme is, the more one can give it a big treatment … [T]ruth is all that matters.”

The Conversation begins with a long shot of Union Square in San Francisco, ever so slowly moving in on the busy lunchtime crowd. As with the entire film, the opening scene was shot on location, in this case unobtrusively with very long lenses that allowed the players to mix in with people going about their normal business. The focus of the shot is at first uncertain, then a mime catches the eye; a tip of the hat to the mime in Blow-Up, it also brings attention to Harry, as the mime follows and mimics his actions. At first Harry does not notice, and then with some effort sheds the unwelcome irritant. This initial piece of business, Coppola has said, is the first invasion of privacy in the movie, which is of course a principal and ubiquitous theme.

A sniper’s crosshairs, focused on a young couple, are much more ominous. Given the period, it would be natural to expect that an assassination is about to take place. But a more intimate sin is occurring. The scope is aiming not a rifle but a sophisticated listening device, one of three devices that are tracking this couple and secretly recording their conversation. Harry is in charge of the operation, and as the camera follows him to the van from where the job is being orchestrated, he is associated with an aural motif: a piece of the conversation that is repeated five times, always matched with a shot of Harry, usually in close-up. The girl, Ann (Cindy Williams), is saddened by an older homeless man she sees sleeping on a park bench. “I always think that he was once somebody’s baby boy,” she tells her furtive companion, Mark (Frederic Forrest), “and he had a mother and a father who loved him and now there he is, half-dead on a park bench, and where are his mother or his father or all his uncles now?” Like the homeless man, Harry seems very much alone, and he prefers it that way. Obsessed with his own privacy, he is dismayed to learn that his landlady has a set of keys to his apartment—solely to save his valuables in case of fire, she explains reassuringly. But Harry has nothing he values, “except my keys,” which he thought gave him exclusive access to his triple-locked apartment. The “action” in his apartment is shot in a distinct style: a static camera, master shot. Harry walks in and out of empty frames; only when the camera seems to realize that he is not coming back, it mechanically pans to pick him up, like a surveillance camera in a convenience store. Not that there is much worth seeing. Harry does not entertain; he spends the evening playing the saxophone to a record of a live jazz performance.

There are two people with whom Harry has some human connection, his assistant Stan (John Cazale) and his lover Amy (Teri Garr). Harry and Stan bicker at the warehouse workshop that serves as Harry’s headquarters. Stan is curious about the content of tapes, but Harry is concerned, and insistently so, only with getting a “big, fat recording.” In two virtuoso scenes, Harry gets just that, piecing together one seamless tape from the fragmented multiple recordings. He is a master craftsman, absorbed in his work. Here the link with Blow-Up is most explicit, as he massages ribbons upon ribbons of tape to create one (ultimately enigmatic) representation of reality, just as the gifted photographer Thomas seeks to do in Antonioni’s film.

With Amy, Harry is, if anything, even more circumspect. He pays her rent, watches her from a distance, and listens to her phone calls, yet she knows nothing about him. When he crawls into bed with her, it becomes clear that he isn’t even going to take off the thin translucent raincoat that he wears throughout the film (despite the fact that it never rains). Harry is often shot through plastic and glass barriers, which both protect and expose—phone booths, curtains, screens, dividers and, as Murch points out, “whenever he’s threatened or something bad is going to happen, he retreats behind” some opaque shield. The raincoat is part of this larger “metaphor of seeing through things,” Coppola explains; it also has an affinity with Harry’s last name, C-A-U-L, as he spells it out on several occasions, which is a thin membrane that encases a fetus. The name serves as a reminder of his childhood frailty (like Coppola, Harry had polio) and the fact that, although now so desperately alone, he was once indeed “somebody’s baby boy.”

Harry’s encounter with Amy ends abruptly; she has grown impatient with his secretive nature. When Amy probes between kisses for innocent scraps of information, such as what he does for work, Harry first lies and then, recoiling from the invasion of his privacy, flees her apartment. The next day brings another unconsummated encounter. Harry goes to deliver his tapes to the director of what appears to be a large if nondescript corporation but is met by the director’s assistant Martin Stett (Harrison Ford) instead. With a telescope between them (one of the constant reminders of secret observation that litter the film from start to finish), the two men awkwardly talk business. Harry’s instructions were to give the tapes only to the director himself. Suddenly the smooth-talking Stett makes a grab for them. Harry wrestles them back and escapes the skyscraper with Stett’s warnings ringing in his ears: “Don’t get involved in this, Mr. Caul … those tapes are dangerous; you heard them, you know what they mean.”

But actually Harry is not quite sure what is on them, and so he revisits the recording. A key part of the conversation had been drowned out by a steel drum. Again with a virtuoso display of craft, Harry manages to isolate the missing line: “He’d kill us if he had the chance.” There it is. Until this point in the movie Harry had protested, in retrospect too much, that what was on the tapes he made for others was none of his business. Yet from that revelation Harry immediately seeks out the confessional, where he has not been in months. He atones for various minutiae—lifting newspapers, impure thoughts—as the camera, as if bored, slowly shifts its focus toward the priest. “This happened to me once before. People were hurt because of my work, and I’m afraid it could happen again,” Harry says. Or does he? As the focus of the image drifts away from him, the track shifts to voiceover, as if Harry can reveal these thoughts only to himself. But he does seek absolution. “I was not responsible,” he insists, “in no way responsible.”

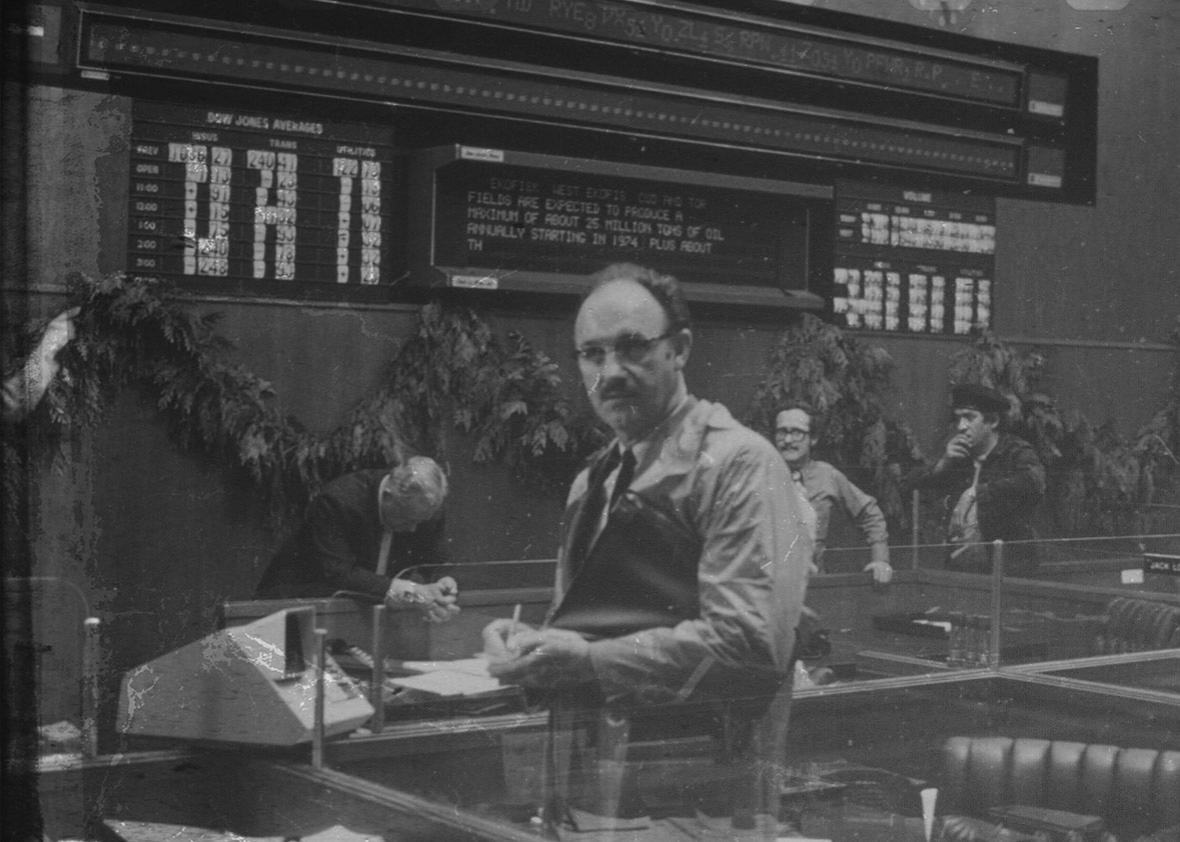

Harry is in crisis: burdened by guilt, followed (on screen) by Stett, his relationships crumbling, he is unable to reach Amy, who has moved and disconnected her phone, and Stan now seems to be seeking employment elsewhere, perhaps with a rival. In a crucial bridging sequence Harry attends a convention of surveillance experts (an actual convention, filmed on location), and from there finds himself with some business acquaintances, girls in tow, back at his warehouse for a few drinks. Harry locks away some papers in a room secured by a chain-link fence, but nothing can protect him from Bernie Moran. Chillingly portrayed by Allen Garfield, Moran, more than Harry, is the Nixon of the piece. Seething, ruthless, amoral, squeezed into an ill-fitting suit, Moran is self-made and proud of it, still walking around with the chip on his shoulder from his tenement youth. Self-declared “best bugger on the East Coast,” Moran is obsessed with the fact that Harry is at least as good as, and certainly more esteemed than, he. If not Nixon himself, Moran would undoubtedly have been at home in the basement of the Nixon White House, plotting dirty tricks; he stalks Harry with almost equal measures of jealousy and respect.

Moran floats the idea of a partnership, but Harry is more interested in being spirited away from the group by Meredith, the model who worked Moran’s display booth at the convention. With her encouragement, Harry shares with another person, haltingly and for the only time in the film, some of his private thoughts. He wonders (obliquely in the third person) whether Amy might return to him. Her response is heartbreaking (“How would I know that he loves me?”), and Murch is justly proud of the three camera moves, slow, rotating reveals (constructed during the editing of the film), which unmask Harry during this exchange.

But no good deed goes unpunished. Meredith is not an angel of mercy; she is an agent of the corporation. She stays behind after the others leave and offers some comfort to Harry, who is shown prone and dazed on a cot, a matching shot that pays off a final overheard reference to the homeless man “half- dead on a park bench,” bereft of the people who once loved him. “Forget it, Harry, it’s just a trick,” she urges. “You’re not supposed to feel anything about it; you’re just supposed to do it.” She ought to know. She slips out of her dress and spends the night. Harry, tormented by the thought of more innocent blood on his hands, dreams fitfully of catching up with Ann and alerting her to the mortal danger: “He’d kill you if he had the chance.” In the morning Meredith is gone, and so are the tapes.

The last 40 minutes of The Conversation flirt again with Hitchcock; except for “the conversation” itself, there is very little dialogue, recalling the long, silent sequences in so many of the Master’s suspense films. Potential threats—the ominous man waxing the floor, the large, unattended dog—come and go without incident, and it turns out that the director got the tapes after all. But neutral locations, like the bathroom, erupt with horrors when least expected. Privacy is again invaded, opaque curtains are parted, translucent barriers bloodied, see-through shower curtains murderous, and Harry’s worst nightmares are realized.

Or not. Harry had it all wrong, as he soon finds out. He heard the tapes incorrectly, misunderstood the intrigue, wept for the wrong victim. Seeing (and hearing) it again in his mind, he reimagines the murder: that’s probably what happened; we’ll never know. But the bad guys—different bad guys than he thought—know that he knows. They call Harry at home and make it clear that they have bugged his apartment. “We’ll be listening to you” is the last line in the film. In the movie’s final sequence, Harry, searching for the bug, destroys his apartment and its contents, fixture by fixture, outlet by outlet, wall by wall, floorboard by floorboard, until he is left, unsuccessful among the ruins, with nothing left but his saxophone. He had not lied to his landlady; none of his possessions mattered to him as much as his keys, or at least what they represented. Which was worse—the violation of his privacy, or that he was out-bugged, possibly by somebody better, perhaps even by Moran? For Coppola, “the tearing down of the room … [was] synonymous with a kind of personal tearing down,” rooted in Harry’s overwhelming guilt. In the end, it occurred to Coppola that he hadn’t made “a film about privacy,” as he had “set out to do, but rather a film about responsibility.” In that sense, finally, The Conversation was not about Nixon at all but what the age of Nixon had taken away.

Excerpt from Hollywood’s Last Golden Age by Jonathan Kirshner, published by Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2012 by Cornell University Press. All rights reserved.