The Intimacy of Walt Whitman’s “America”

“What is a poet? He is a man speaking to men.”

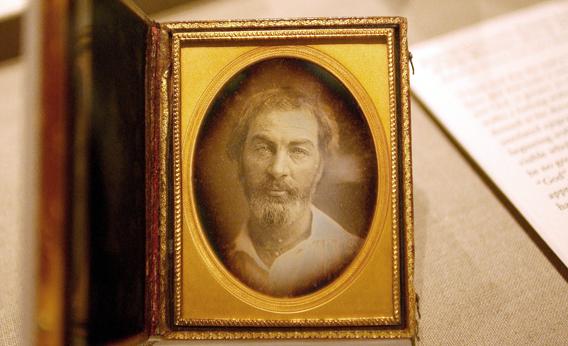

Photo by Chip East/Reuters

Each of the many readers who love Walt Whitman creates his or her own version of him: The poetry is so vast, so manifold—and exists in so many revised forms—that Whitman is the American poet most like the fabled elephant as described by blind witnesses, each touching a different part of the creature thinking it to be a wall or a snake. Yet we tend to call him, familiarly, Walt. After all, what he assumes we will assume. He has told us so, directly and honestly. He hides nothing in his work; there are few metaphors, few symbolic gestures, little that is oblique. It can be hard to remember how strange this familiar presence we call Walt really is.

A broad consensus looks on Leaves of Grass as the fountainhead of American poetry, but though many follow this or that direction of his style, few take up the essential core of his endeavor, I think. His perceived plainness (how plain can a style based on near-infinite periodic sentences be, really?), his directness, his intimacy, his transparency clearly inspire many of his poetic descendants. But something deeper and richer and more dangerous—no, more impossible—is rarely broached, and scarcely mentioned.

Whitman’s famous lines “Camerado, this is no book;/ Who touches this touches a man” take us to the crux of the matter. How do we understand this utterance? That there is an unmediated continuity between poet and text, text and reader, poet and reader? How true can this be? More radically than any other poet of his time, Whitman throws his famous hat in the ring of the purely textual (as opposed to the oral tradition to which Poe, for instance, remains in allegiance). Not the voice, not the song, but the book connects us directly and intimately to Whitman.

My songs cease—I abandon them;

From behind the screen where I hid I advance personally, solely to you.

Camerado! This is no book;

Who touches this, touches a man;

(Is it night? Are we here alone?)

It is I you hold, and who holds you;

I spring from the pages into your arms—decease calls me forth.

O how your fingers drowse me!

Your breath falls around me like dew—your pulse lulls the tympans of my ears;

I feel immerged from head to foot;

Delicious—enough.

Enough, O deed impromptu and secret!

Enough, O gliding present! Enough,

O summ’d-up past!

“My songs cease ... I advance personally, solely to you ... decease calls me forth.” Go to the Oxford English Dictionary and unpack that odd word immerged. This is no clear, transparent, plain statement. It is a miracle. Likewise, “who touches this [book] touches a man” is no straightforward proposition. If we try to understand it as such, we run into the fact that it is false. Who touches this book touches a book, and confuses a book with a person at his or her peril. Perhaps then it is a metaphor. But to understand it as a metaphor reduces the intimacy the passage asserts: Who wants to be embraced by—to make love to—a metaphor? The only remaining option is to understand Whitman’s statement as a miraculous “impossibility,” like Jesus’ “Lo I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.” In that case, “Who touches this [book] touches a man” is neither a simple statement of fact nor a metaphor: It is a transubstantiation, the word made flesh. So, “decease calls me forth” follows from “I spring from the pages into your arms.”

Thus far people of Christian cultures at any rate may follow Whitman’s strangeness as being based on a familiar model, but even here we are defeated, for Whitman does not claim to be any kind of Christ, but only “one of the roughs.” The divine—the Godhead, or Emerson’s “The Oversoul”—is, by an act of poetic jujitsu, flipped to become, first, America, and ultimately the body of humanity. For Whitman, there the miracle of transforming book to man does not need anything supernatural; all that is required is humanity, and for Whitman America is where this fact is to be fully realized.

Where are the poets who flock to Whitman’s transubstantiation? Mostly, we lack the visionary strength to follow him there. For most of us most of the time, Wordsworth’s “What is a poet? He is a man speaking to men,” when translated out of its gender-specific form, is a much more congenial model, and for the most part there we American poets rest, paying lip service to Whitman, but following Wordsworth. We lack the power to “spring from the pages into your arms” from “decease.” But how we love it when Whitman says it; how we long for him to do it.

Whitman’s project was nothing less than the reinvention of the human voice, and the human consciousness behind that voice, through writing—through the process of writing and writing’s product, transmogrified. There are volumes yet to be written about his achievement, the often misconstrued depth of his ambition for humanity.

However—in an improbable historic irony—there emerges from the shadows, come down to us by circuitous routes, a certain artifact: a recording purporting to be of Whitman himself, made by Thomas Edison. If you are interested in Whitman, probably you have already heard it, and considered the dispute among experts about whether the recording is authentic.

If you want to peruse, or enter, the dispute, it is easy to find. For me, it is much more fruitful to listen to the recording—the deliberate, overarticulated voice, the grinding sound in the background which is the recorder recording itself (how appropriate to Whitman!). It sounds like a gravel-grinder in Hell.

The overall effect is sublime.

Is it Whitman? Who hears this voice hears a man. Out of the text, out of the abandonment of song, a living voice arises, transubstantiated. How glorious to hear him, whoever he might be. He reads the first four lines of a six-line poem called “America” (why only four? A revision of the poem? Or was that all the time the wax cylinder allotted? Does this elision itself constitute an abandonment of song?). Decease calls him forth. He reads the poem that is the namesake of the nation in which he had such mystical faith, such metaphysical hope. For the duration of the recording, the tension between orality and text is resolved. He springs from the pages into our arms.

“America”

By Walt Whitman

Centre of equal daughters, equal sons,

All, all alike endear'd, grown, ungrown, young or old,

Strong, ample, fair, enduring, capable, rich,

Perennial with the Earth, with Freedom, Law and Love,

A grand, sane, towering, seated Mother,

Chair'd in the adamant of Time.