Truth in Darkness

Herman Melville is a master of conveying nature as a mysterious language we must speak but do not know.

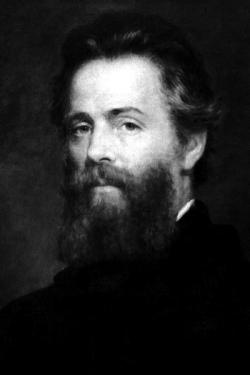

Photograph courtesy Library of Congress.

In a severe, unsentimental passage about nature, Wallace Stevens wrote, “It was only a glass because he looked in it. It was nothing he could be told.” Moreover, “It was a language he spoke because he must, yet did not know./ It was a page he had found in the handbook of heartbreak.”

Our beloved earth is unlike us: fundamentally unlike the terms we use to perceive it. And it will devour each of us. In the poem I have quoted, “Madame La Fleurie,” Stevens takes this way of thinking about Mother Earth so far that it becomes, in a characteristic move, bemused and comic, yet still terrifying: “His grief is that his mother should feed on him, himself and what he saw,/ In that distant chamber, a bearded queen, wicked in her dead light.”

I tend to think of “Madame La Fleurie” when I read poetry or prose that moralizes the natural world in a way I find glibly sunny: The flower opens, or the birds fly up, and everything is OK, or closer to OK than you might have felt.

Perhaps inconsistently, on the other hand, I tend to admire poems that look into nature and make it into a glass reflecting not uplift or reassurance but something disturbing. That dark understanding may be a mere human projection imposed on the natural world just as much as the uplift. However, it not only suits me better, I find it more true. Maybe I am not merely attached to darkness in a sentimental way; I can hope that what I value is truthful attention. As with John Clare's poem “Badger,” profoundly respectful attention to nature can find in it a language for human qualities—moral mysteries reflected by nature: that language that, in Stevens' terms, we must use, though we do not really know it.

In American literature, one of the great works that convey nature as a mysterious language we must speak, but do not know, is Herman Melville's Moby Dick. The novel is so dark, disturbing, and obsessive that it more or less wrecked the author's career. Readers who had admired Melville's popular hits, the straightforward Typee and White-jacket, didn't know what to make of the coiled, mystical, detailed, crazy-seeming Moby Dick.

Melville also wrote poems, brilliantly. Here, as this month's Classic Poem, is one of the best-known of them, “The Maldive Shark.” The “sleek little pilot-fish” that guide the “pale sot” of the shark function as the shark's “eyes and brains.” Those nouns, eyes and brains, are not literally considered as food, but the poem in an irrational or subliminal way associates them with meat for the consuming “charnel of maw” in the shark's “Gorgonian head.” I find an appealingly aggressive, tough quality to the poem, almost as though the poet is thinking about more sentimental, cloying approaches to this same material, such as symbiosis, or the grace of fish. Like Melville's prose, “The Maldive Shark” has the conviction of its dark, fortissimo manner.

Click the arrow on the audio player below to hear Robert Pinsky read Herman Melville's "The Maldive Shark." You can also download the recording or subscribe to Slate's Poetry Podcast on iTunes.

"The Maldive Shark"

About the Shark, phlegmatical one,

Pale sot of the Maldive sea,

The sleek little pilot-fish, azure and slim,

How alert in attendance be.

From his saw-pit of mouth, from his charnel of maw

They have nothing of harm to dread,

But liquidly glide on his ghastly flank

Or before his Gorgonian head;

Or lurk in the port of serrated teeth

In white triple tiers of glittering gates,

And there find a haven when peril’s abroad,

An asylum in jaws of the Fates!

They are friends; and friendly they guide him to prey,

Yet never partake of the treat—

Eyes and brains to the dotard lethargic and dull,

Pale ravener of horrible meat.

Slate Poetry Editor Robert Pinsky will be joining in discussion of Herman Melville's "The Maldive Shark" this week. Post your questions and comments on the work, and he'll respond and participate. For Slate's poetry submission guidelines, click here. Click here to visit Robert Pinsky's Favorite Poem Project site. Click here for an archive of discussions about poems with Robert Pinsky in "the Fray," Slate's reader forum.