I’ve spent the week so far reading mid-century-style: pocket paperbacks and folded pages, making notes in the margins with ballpoint pens. When I finish Shirley Jackson’s 1951 novel Hangsaman today, though, I immediately head to the 21st century—I take out my phone and start Googling furiously. I know Jackson as the author of “The Lottery,” and I packed Hangsaman for this beach trip because of a great piece on The New Yorker’s Page-Turner blog about all the letters the magazine received after they published that story. But I know very little about Jackson, and even less about Hangsaman—and it’s the kind of book that sends you searching immediately for other people’s ideas of what it is you’ve just read.

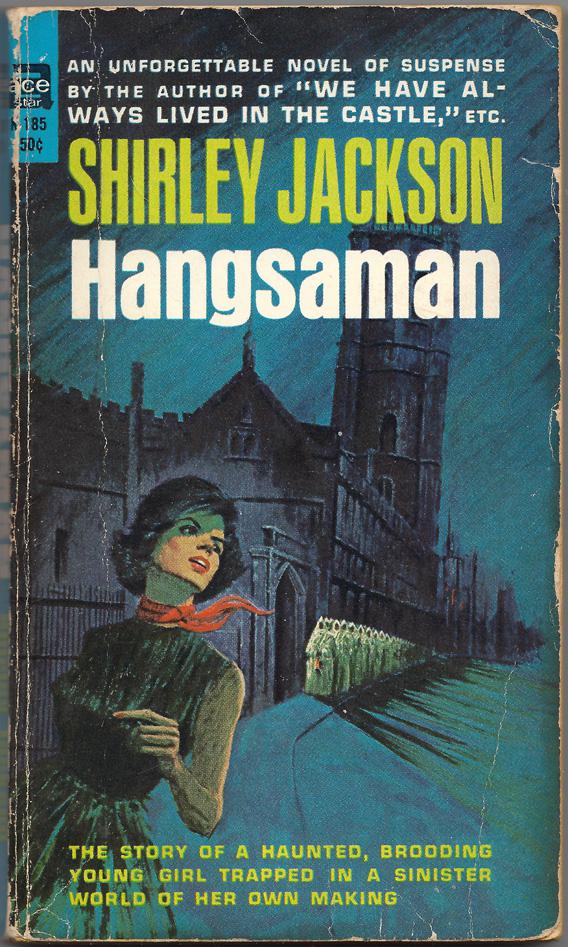

My mass-market of Hangsaman was packaged for 1950s readers as a traditional spine-tingler—“AN UNFORGETTABLE NOVEL OF SUSPENSE,” reads the front cover, “FROM THE AUTHOR OF ‘WE HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN THE CASTLE,’ ETC.”—and I spent much of the novel expecting something gruesome to happen at every turn, the way it would in a contemporary Gothic. (Like, for the heroine to be chased through campus by terrifying figures in white robes, which happens on the cover but not, in fact, in the novel.) It took me a long time to accept the book for what it was and settle into its peculiar rhythms, following poor Natalie Waite as she comes completely unhinged in her proper northeastern college for women. Only now, having finished the book, do I begin to feel as though I understand what kind of novel I’m reading, and even so I wouldn’t at all be surprised to find out I’m completely wrong—that a wild supernatural twist happened and I missed it, that Natalie’s father’s been dead since the first page, or something.

I go first to Ruth Franklin’s blog; she’s the excellent critic (and Tweeter) who wrote the Page-Turner post and who, I recall, is writing a biography of Jackson. I find a post about the folk song that’s threaded through the book—I play the video right there on the beach, holding it up to my ear to make out the tune through the afternoon wind—but very little else that can help me unravel the mysteries of Hangsaman. Jackson’s Wikipedia entry suggests that she based Hangsaman on a locally notorious missing-persons case, a Bennington student who disappeared into the dark woods in 1946, never to be seen again.

Courtesy Ace Books

Now what? I remember seeing in my office, earlier in the year, a new Penguin Classics edition of the book with a foreword by … someone great?, so I download the e-book and check it out. It’s by Francine Prose, and indeed it’s fascinating:

“Natalie is lonely at school. And because of who she is, and because of what kind of novel this is, her loneliness is terrifying. The dangerous power of awareness, quotidian social brutality, loneliness, and existential fear propel Hangsaman toward the edge of becoming a psychological thriller, rather like one of Patricia Highsmith’s, only less physically violent, funnier, more lyrical, imaginative, and interior.”

At the very least I’m reassured that I didn’t miss some enormous plot point. Instead, I’m left with the thoroughly enjoyable activity of chewing over the book I’ve just read: thinking back on Natalie’s voices, her diaries, her puffed-up father and desperate mother, the man at the party, the one-armed diner and the best friend, only some of whom, it’s clear, actually exist. And I come back over and over again to the letter Natalie’s father sends to his madly unhappy daughter in November of the school year, a letter that lays bare how alone Natalie really is:

“My ambitions for you are slowly being realized, and, even though you are unhappy, console yourself with the thought that it was part of my plan for you to be unhappy for a while. The fact that you associate intimately with girls who do not care for the things you do should strengthen your own artistic integrity and fortify you against the world; remember, Natalie, your enemies will always come from the same place your friends do.”

There aren’t that many books being published in mass-market today willing to be so uncompromisingly cruel, so strange and discomfiting. (The Penguin Shirley Jackson reprints are trade paperbacks, not mass-markets; or, as my iPhone Kindle purchase today proves, they’re just “content,” with trim size rapidly becoming an artifact of another world.) I’ve tried to figure out when publishing houses stopped using mass-market paperbacks to send serious literary writers out into the world. The evidence on my shelves suggests that even into the 1980s, writers like Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Ann Beattie, and John Gardner were seeing their books released in mass-market. But soon after that, they weren’t.

My hunch is that the establishment of the trade paperback as an exciting format for lit-fiction—cemented by the amazing Vintage Contemporaries line, launched in 1984 and a fabulous success almost instantly thanks to Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City—meant that suddenly every author wanted a large-format paperback edition for herself. They also cost more: more money for publishers, higher royalties to authors. So where once most trade paperbacks were, as this blog post points out, academic books, that format now became a way to differentiate high-toned fiction from its pulpier, poppier, mass-market brethren. The bet was that readers would pay for quality. For a while, they did.

Now, of course, the only thing I’m willing to pay for is speed. I spent $8.89 to download a book in seconds, even though it’s just data, words on a screen, more ephemeral even than the shabby mass-market tucked into the cupholder of my beach chair. Fifty years from now Hangsaman will be over 100 years old, and this little object that once sold for 50 cents may well still survive—in my daughter’s house, or in a thrift shop somewhere, or on the shelves of some other mass-market fetishist like me, carefully tending the last remaining treasures in his collection. That $9 Kindle version will be long evaporated into the ether, just another obsolete file format, more orphaned data lost in the dark where no one will ever find it.