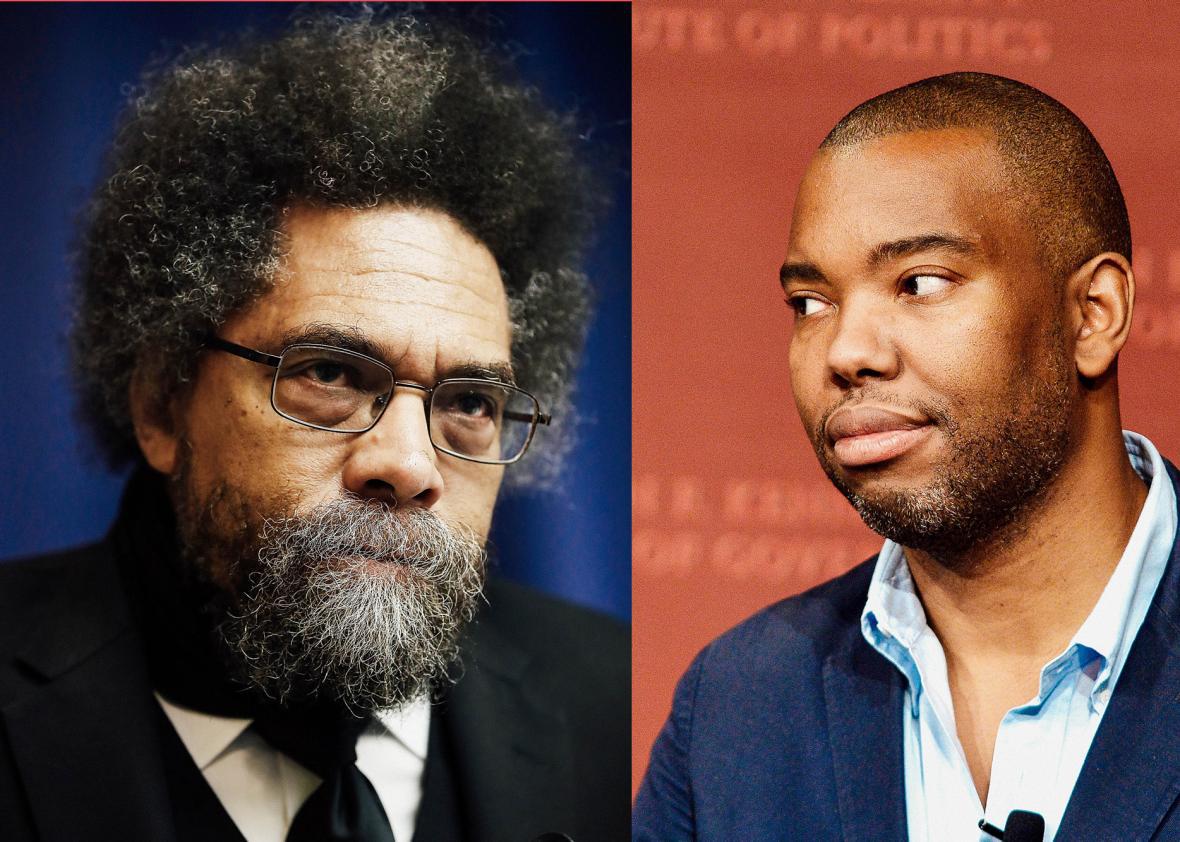

It’s not an overstatement to say that, if you are a young writer who interrogates American race relations and white supremacy, Cornel West is the foundation upon which you stand. Alongside the likes of Kimberlé Crenshaw, Angela Davis, Toni Morrison, and, of course, James Baldwin, West’s work is part of the canon that teaches younger writers how to think and write about race. It is impossible to imagine a writer like Ta-Nehisi Coates having come into existence without a book like West’s Race Matters, which, in the wake of the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, helped popularize the thesis that anti-black racism was inextricably entangled with almost every aspect of American politics and culture—including, most crucially, our capitalist economy.

West’s importance to contemporary black thought is what makes his recent Guardian broadside against Coates so disheartening. Not only is it a case of one of black thought’s elder statesmen attempting a hatchet job on a younger writer, West thoroughly botches the job via disingenuous readings from which a reader is tempted to conclude one of two things: Either he hasn’t read We Were Eight Years in Power very closely, or he has intentionally misrepresented Coates’ writing in an attempt to bolster his own brand. (It is probably not a coincidence that West’s Twitter feed is full of plugs for the 25th-anniversary edition of Race Matters.) Coates addressed West’s attack but deleted it along with his entire Twitter account. The New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb also assailed West on Twitter, accusing him of “cloak[ing] petty rivalry as disinterested analysis.” It’s hard to say for sure, of course, whether West was motivated more by competitiveness or by ideology. But it’s pretty shocking that he authored a partially baked, inaccurate hot take that all but labels Coates a stooge of white liberalism—an accusation that feels especially reckless coming from a writer of West’s stature.

West’s interpretation repeats some familiar criticisms of Coates’ work, namely the charge that Coates portrays white supremacy as an intractable, omnipotent force that we might never overcome. For critics of Coates, this portrayal betrays an apolitical pessimism that neither takes stock of black resistance to structural racism nor charts a path forward. But West takes this critique a step further, arguing that Coates “hardly keeps track of our fightback, and never connects this ugly legacy to the predatory capitalist practices, imperial policies (of war, occupation, detention, assassination) or the black elite’s refusal to confront poverty, patriarchy or transphobia.” For West, Coates’ alleged silence around these issues is exactly what has garnered him acceptance among white audiences: He decouples anti-racist thought from an intersectional critique of state power, effectively rendering himself a “neoliberal” mouthpiece of the state.

West’s reading is blinkered in several key ways. Let’s take his argument that Coates ignores black “fightback.” While Coates might eschew calls for conventional hope, he does not fail to track the scope and import of black resistance. “My ancestors,” he writes in Eight Years, “had not lived in times of hope … They were Celia, enslaved, hanged for murdering her master, but who for a brief moment, stick in hand, lifeless body beneath her, knew freedom … They were Ida B. Wells, who defied the great wave of lynching even when the men whom it victimized would not, even as the country turned away from her … the lessons they passed down were not about an abstract hope, an unknowable dream. They were about the power and necessity of immediate defiance.” To Coates, these women are heroes because they resisted in moments when resistance’s benefits would not be immediately legible. Here, the absence of hope does not minimize the import of black resistance; rather, it makes that resistance monumental in scale, turning it into the principled opposition of those who opt for dignity over inhumanity. These moments of resistance are gestures toward a better future that history’s forgotten subjects recognized they’d never had the privilege of knowing but fought for nevertheless.

Elsewhere in Eight Years, Coates argues that the Civil War’s importance to black history lies in “the unsettling fact that black people in this country achieved the rudiments of their freedom through the killing of whites.” He writes of his personal discovery that “Nat Turner did not fight alone … but was part of a resistance that was as old as the banditry that made the West and would be here until the West crumbled to dust.” What kind of patsy to white liberalism mentions Nat Turner admiringly as a counterweight to white-supremacist exploitation? These words aren’t the expression of an apolitical pessimism that doesn’t recognize black resistance but an acknowledgement we must resist even though our opposition guarantees us nothing.

And while it is true that Eight Years doesn’t engage with questions of U.S. imperialism, transphobia, sexism, and predatory capitalism in an exhaustive fashion, it feels like West is being disingenuous when he claims that Coates has failed to frame racism as part of a matrix of oppressions. The book’s epilogue gestures toward a global context in which “Americans are all white” as a result of the benefits we reap from the spoils of American imperialism and its history of “torture, bombings, and coups d’état carried out in our name.” In the same epilogue, Coates writes that he sees “the fight against sexism, racism, poverty, and even war” as related endeavors in the struggle for a more just world. There is something mildly defensive in this epilogue, as if Coates feels the need to guard himself against critics who see his focus on race as myopic. But if we think of Eight Years as an intellectual autobiography that shows Coates’ mind in motion, this epilogue promises that his next iteration might indeed find the writer addressing the intersection of race, class, and gender more substantially.

Rather than engaging Coates in good faith in order to encourage this next iteration, West wrote a piece in which he comes off a bit like a vengeful father attempting to strangle a child before it has the chance to grow. The misreadings I’ve pointed out above are common among Coates’ critics, but West’s piece stands out for its viciousness and rhetorical sloppiness. At one point, he claims that “Coates’ allegiance to Obama has produced an impoverished understanding of black history,” and goes on to cite a passage that, out of context, seems to situate Obama as the heir to Malcolm X’s radical black politics. Anybody who’s read the book knows that the quote West cites arrives in an essay titled “The Legacy of Malcolm X,” which probes the ways in which Malcolm X’s politics were intertwined with a moral conservatism and the myth of self-making. It is in the context of Malcolm X’s image as a self-fashioned and morally pristine patriarch that Coates compares the Muslim preacher to Obama—another black man who chronicled his own self-fashioning and is given to a flawed moral conservatism that Coates repeatedly critiques as insufficient.

Such moments of insincerity are what make West’s piece so disturbing. They suggest that West came to extinguish another, younger writer’s light rather than meaningfully engage him as an interlocutor. This attempt isn’t befitting of an elder statesman who, even as he critiques and challenges, should in theory want to nourish other writers who share his desire to write America closer to true democracy. For those of us who, like Coates, find solace in being part of a community and lineage of black writers, West’s critique breaks the promise of that community.