This has not been a good year for the calm, measured, contemplative act of reading, as every book publisher can attest. Settling down with a book felt a bit like slipping into a hot bath while the fire alarm was going off. For those of us who took the time and mental space for the task, however, books provided not just a refuge but the big picture, a better understanding of this confusing world and a reminder that every historical period has its trials, terrors, and transcendent moments. Here are some of books that broke through the noise.

Age of Anger: A History of the Present by Pankaj Mishra

Read Laura Miller’s review of Age of Anger.

Listen to Isaac Chotiner’s interview with Pankaj Mishra.

Of all the books I read in 2017, this is the one I thought of most often when trying to make sense of our current political mess. Mishra argues that the rest of the world is now going through the convulsive reaction to modernization that the West endured in the 19th and 20th centuries but has conveniently forgotten in the intervening years. He originally intended Age of Anger to be a way to place phenomena like Islamism and Hindu nationalism in a context comparable to anarchist terrorism in the 1800s and fascism in the 1930s, but Western history caught up with him. Mishra views many seemingly opposed political insurgencies as sharing a rejection of the globalized, cosmopolitan professional class and its values, and asks if, however toxic the manifestations of that rejection, they haven’t got a point.

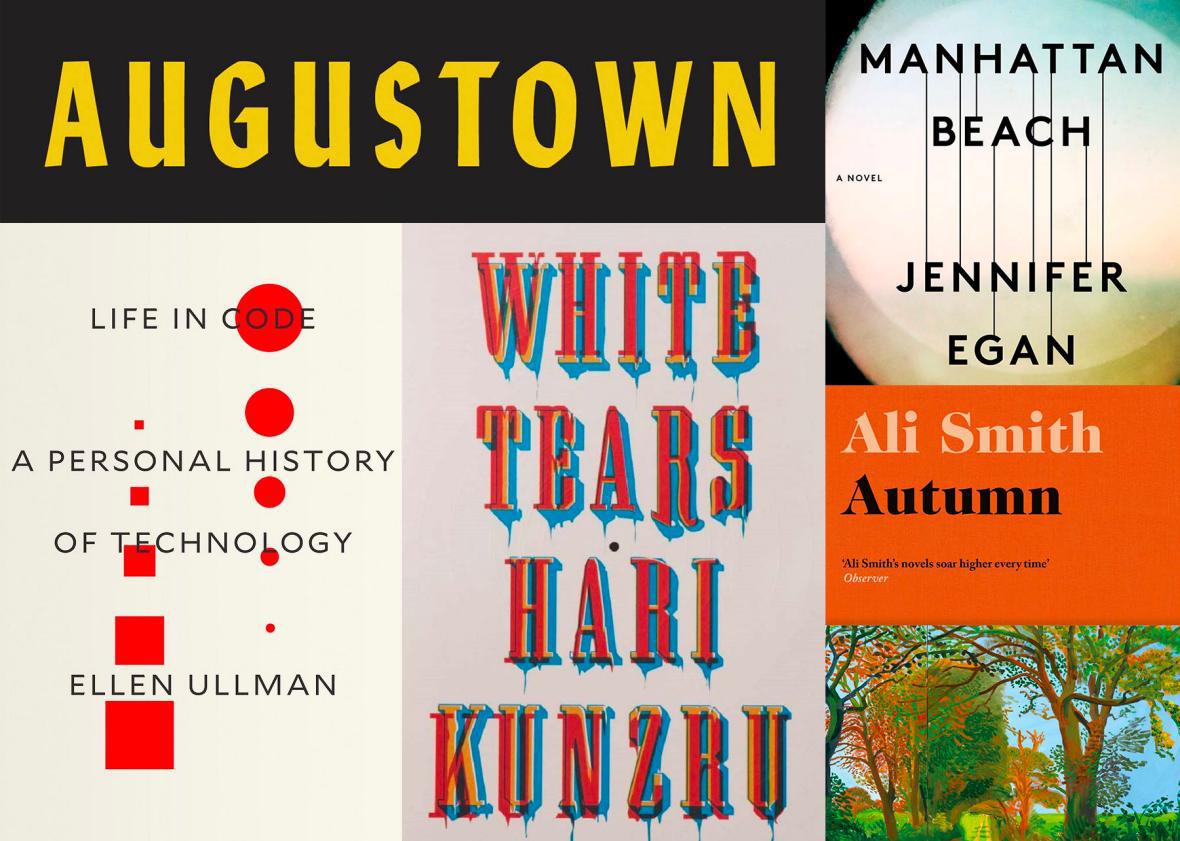

Augustown by Kei Miller

Set in the hardscrabble Jamaican neighborhood that gives the book its title, this slender novel hinges on a single catastrophic choice: A schoolteacher unable to embrace his own blackness cuts off the dreadlocks of one of his students. How this fraught action leads to what Augustown’s residents refer to as an “autoclaps” is a surprisingly intricate and tense tale, for all its brevity. It has to do with a preacher from the 1920s who might have possessed the power of flight and a gangster named Soft-Paw, after his silent tread. Binding the novel’s many threads together is Miller’s musical yet unflowery prose style (he is also a poet) and the sense that, for all the traits that make Augustown unique, it is a village like any other, full of unforgettable stories and characters. “Each day,” the novel’s mysterious narrator explains, “contains much more than its own hours, or minutes, or seconds. In fact, it would be no exaggeration to say that every day contains all of history.” The same could be said of Augustown itself.

Autumn by Ali Smith

Read Laura Miller’s review of Autumn.

The first in a quartet of novels that the brilliant Smith has been writing in a white heat, attempting to chronicle the post-Brexit distress of her native Britain as it unfolds, Autumn describes how Elizabeth, a young, low-level university lecturer, makes it through the season after the vote. Her oldest friend (at 101 years) is dying. She is researching the life of a radiant, rebellious, hedonistic woman artist of Swingin’ ’60s, the real-life Pauline Boty. And meanwhile, England seems to be coming apart at the seams. However stormy the events and themes of Smith’s work, their presiding spirit is sunny, witty, and expansive, and Elizabeth finds hope and comfort where she least expects it: in the life force of artists, in unruly women, in the English countryside, and in love. Bliss from beginning to end.

The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America by Frances FitzGerald

The eminent historian surveys an American religious and political movement too often seen as monolithic and unchanging, revealing it to be riven with schisms, uprisings, power struggles, and transformations. Nevertheless, certain perennial questions plague American evangelicals as they move in and out of relative power: How much freedom of conscience can Protestantism accommodate? How much power should congregants give to the clergy? Is it advisable or even possible to participate in the affairs of a fallen world? Among the more fascinating topics FitzGerald covers is the long history of liberal evangelism, now largely obscured by the predominance of conservatives today. To read this sweeping yet meticulous book is to realize just how much evangelical thinking permeates American culture, whether we choose to admit it or not.

Golden Hill by Francis Spufford

A smooth-talking, cagey stranger comes to town, and when the town is as small and as rife with intrigue as New York in 1746, everyone speculates madly about what his game might be. Richard Smith, freshly arrived from England, comes bearing a formidable bill of exchange, requiring that the town bank hand over the fabulous amount of one thousand pounds sterling. While the bank scrambles to come up with the cash, and to verify Smith’s legitimacy with its British counterpart, the newcomer embroils himself in local power struggles, a scary Guy Fawkes Day celebration, and a prickly romance with the banker’s sharp-tongued daughter. Partly inspired by such rowdy 18th-century classics as Tristram Shandy, Golden Hill is a smart, sparkling entertainment with a sting in its tail.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann

Read Tom Drury’s review of Killers of the Flower Moon.

A fusion of true crime and history, the latest nonfiction page-turner from the superb journalist David Grann recounts a series of killings among Osage Indians in Oklahoma in the early 1920s. The tribe’s leaders had shrewdly negotiated a land deal with the federal government that left them in possession of the mineral and drilling rights on what they retained of their ancestral land. When oil was discovered on that land, the Osage became the wealthiest community per capita in the nation, a situation that racist white authorities considered intolerable. Grann uses the successful federal investigation into who killed over two dozen tribe members—it coincided with the establishment of the FBI—to illuminate the seedy, brawling world of boomtown Oklahoma. Oh, and as if that’s not enough, there’s also a twist at the end.

Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology by Ellen Ullman

Read Laura Miller’s interview with Ellen Ullman.

This collection of essays, providently released just as the infamous “Google memo” was made public this summer, looks back over Ullman’s 20 years spent working as a software engineer, from the birth of Silicon Valley in the 1970s through the heyday of the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. As the foremost literary voice on the experience of writing code, Ullman reveals that the work is anything but dispassionate. Instead it’s “an illness, a fever, and obsession. It’s like riding a train and never being able to get off.” The infrastructure of our digital lives is built by coders, and Ullman is the rare writer who can illuminate how their minds work for a nontechnical readership. Life in Code includes deep dives on such puzzles as the viability of artificial intelligence, the paradoxes of virtual flirtation, and the surreal euphoria of living through the industry’s most hubristic periods. At once immediate and thoughtful, this collection is an invaluable window into a culture that too often seems opaque.

Manhattan Beach by Jennifer Egan

Read Laura Miller’s review of Manhattan Beach.

Listen to Slate’s Audio Book Club discuss Manhattan Beach.

On its surface an old-fashioned historical novel, set on the homefront in Brooklyn, New York, during World War II, this book has deep currents that get under your skin. Anna Kerrigan, whose father vanished in the 1930s, goes to work in the Brooklyn Naval Yard, defying tradition to become a civilian diver. Meanwhile, a mid-level gangster named Dexter Styles dares to imagine a more legitimate and patriotic role for his employer in American society. The war is immense, grand, and remote. Egan palpably recreates the sights, smells, and sounds of a vanished world, but the spell this novel casts is hard to define. Its stately rhythms are restoratively and profoundly satisfying, the perfect antidote to a jangled year.

This Long Pursuit: Reflections of a Romantic Biographer by Richard Holmes

I can count on two hands the authors whose every jotting I’ll read no matter what the subject, and Richard Holmes is among them. Fortunately, his most common subject, the epochal cultural and social movement that was Romanticism in the 19th century, is fascinating. Our greatest living biographer, Holmes’ particular interests are the Romantic poets (his masterpieces include lives of both Shelley and Coleridge) and the scientists who often corresponded and even collaborated with them during this period of remarkable intellectual and artistic ferment. In this collection of essays on the biographer’s art, he gives particular attention to women, from Mary Wollstonecraft to the little-known Margaret Cavendish, people whose lives were often less documented than their male counterparts. And he considers his own professional arc, from adamantly unattached freelancer to, late in his career, a respectable resident of academia and a teacher. His credo as a biographer is paradoxical: He describes it as “a simple act of complex friendship,” but every word he writes in his pursuit of this paradox is golden.

White Tears by Hari Kunzru

Read Laura Miller’s review of White Tears.

Despite its Twitterrific title, Kunzru’s novel is a subtle and unsettling ghost story. Two young white friends, the narrator and his trust-funded partner, revere the blues, “lone guitarists playing strange abstract figures, scraping the strings with knives and bottlenecks and singing in cracked, elemental voices about trouble and loss.” The pals open a Manhattan recording studio that specializes in making new recordings sound old. Their worshipful yet parasitical relationship to black culture takes a weird turn when a fake blues track they cobble together from street recordings suddenly takes on an independent, historical existence; the artist they concocted may even be a man who still walks the earth. Rarely has a novel so skillfully captured the uncanniness of art, the way it can make the nonexistent feel more real than life itself—or the peril of forgetting the difference between them.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

And read more of Slate’s coverage of the best movies, TV, books, and music of 2017.