You should not use the word love lightly. Love, about a person, means that every inch of them delights you, even the parts that also cause you pain or terror. It means you care about their flourishing; their way of seeing is dear to you; you want to stroke their hair and serve them cocoa; their words take up residence in your mind and rearrange the furniture. I am confident in pronouncing that people will love the first volume of Philip Pullman’s trilogy, The Book of Dust, with the same helpless vehemence that stole over them when The Golden Compass came out in the mid-’90s, or even when they first met their partners or held their newborn children. Pullman, now 70 and living in Oxford with his wife, a teacher, is simply one of the best storytellers to wave his hand over English literature. La Belle Sauvage (the first installment of this series set in the same dusky and glimmering multiverse as His Dark Materials, a world largely mute since 2000’s The Amber Spyglass) excites a specific enthrallment that is all the headier for being familiar. The Book of Dust is love—nostalgic, warming, pure—at first mote.

Pullman has always been a writer temperamentally opposed to the categories his talent overflows anyway. He is deeply allusive—his latest title quotes Rousseau’s “noble savage” doctrine—and fitfully allegorical, but he seems drawn first and foremost to emotional complication, to the pulses of imagination and impulse that accompany our thinking. His novels, sturdy enough to contain ideas without sinking under them, are stories before they are anything else; their striations of meaning reveal themselves over time. Borrowing from spy thrillers, fantasy epics, steampunk odysseys, and Dickensian bildungsromans, the books are unplaceable, like a tune you might recall from childhood, or a dream. Still, Pullman unboxes a distinctly Romantic vision, full of Blake (especially the Songs of Innocence and Experience) and Blake’s rereading of Milton, whom the former poet famously declared was “of the devil’s party without knowing it.” In interviews, Pullman has attacked “the merciless reductionism of doctrines with a single answer.” He has decried the way organized religion demeans sex and the physical world. Knowledge and the soul continue to occupy him in La Belle Sauvage. Here, though, he turns away from the Adam and Eve/satanic fall framework, toward biblical tales of the flood, Greek myths, and knightly quest narratives replete with fairy folk and beweeded river gods. The sheer polyphony of his sourcing is audacious, and it shouldn’t work, but it does; reading this novel is like standing in a room in which suddenly all of the windows have blown open at once.

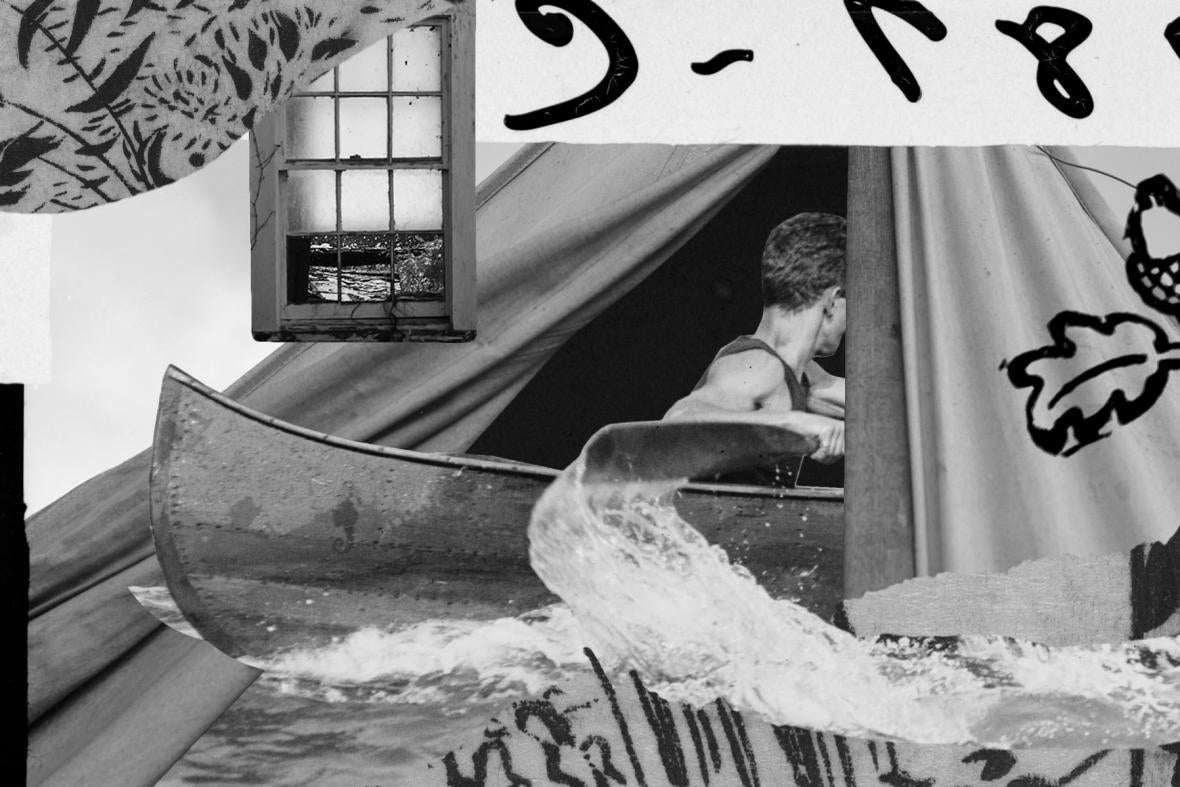

© Michael Leckie

The main character of La Belle Sauvage is a boy with a canoe. His name is Malcolm, and his daemon (the soul-partner shadowing all humans in the world of His Dark Materials, a talking animal) is Asta, and they are bright, curious, handy, and decent. Working at his parents’ inn, Malcolm “came to think of himself as lucky, which did him no harm in later life. If he’d been the sort of boy who acquired a nickname, he would no doubt have been known as Professor, but he wasn’t that sort of boy.” A natural observer and helper, Malcolm hears about a baby given into the care of the nuns across the river. The infant, Lyra, seems to have spooked some unsavory parties, including the Consistorial Court of Discipline, a sort of secret police for the Handmaid’s Tale–style theocracy that has consumed Pullman’s version of England. The first part of the book unfolds like a Le Carré thriller seen through a looking glass, darkly: Malcolm falls in with a group of rogue scholars dedicated to fighting the church after he intercepts a carved acorn with a secret message inside. His discovery puts him on a collision course with the college’s alethiometer expert, Dr. Hannah Relf, and several figures fresh from the His Dark Materials trilogy, including Lord Asriel, Mrs. Coulter, the gypsy Farder Coram (plus Sophie, his wondrous cat daemon), and the witches of the north. Meanwhile, the rains fall and the rivers rise. When the inevitable flood bursts forth, Malcolm finds himself in a phantasmagoria of gray water and fog, piloting his canoe toward Oxford with the baby Lyra and a scornful, bitter teenager named Alice.

Post-flood, La Belle Sauvage becomes an intoxicating and dreamy thing, a mixture of The Odyssey, the Bible, The Red Book, and The Faerie Queene, with its eldritch encounters and wild Englishness. Tender feelings start to unfurl between Malcolm and Alice, who is more complex and gentle than she appears. Meanwhile, the children are pursued by one of the most appallingly hypnotic villains I’ve ever encountered in literature, a handsome madman with a three-legged hyena daemon. George Bonneville represents hypocrisy, sexual predation, and self-loathing. (In one sickening scene, he beats the hyena, his soul’s crippled second body.) Yet for all his allegorical charge, Bonneville is irreducible, a genuinely terrifying psychic boogeyman. Pullman may write crackling adventures, but he also possesses what feels like direct access to everything that is wordless and watery in the human subconscious. There are, as one gypsy messenger puts it, “things [in the deep that get] disturbed, and things in the sky too”—the nameless truths that children know, insoluble by either flood or metaphor.

I absorbed La Belle Sauvage in intense, immoderate bouts of pleasure, horror, pain, and love. Part of this heightened experience relates to the electric emotional content that Pullman so deftly handles; part of it is his sure command of centuries of resonant English poetry and philosophy. (Perhaps such a duality is what it means to straddle “children’s literature” and “literature”: Pullman pulls on our sense of story, the music of story, as well as on the powerful heritage of the mind illuminating our shared canon.) And a huge part of Pullman’s magic must arise from the seaworthiness of his writing, the linguistic carpentry that can nimbly ride the deeper currents he’s summoned. Pullman perfectly parcels out feeling and suspense along a sentence. Consider the very first line of the book, which distributes detail at a lilting, unhurried clip while using a pileup of clauses to stoke our curiosity:

Three miles up the river Thames from the center of Oxford, some distance from where the great colleges of Jordan, Gabriel, Balliol, and two dozen others contended for mastery in the boat races, out where the city was only a collection of towers and spires in the distance over the misty levels of Port Meadow, there stood the Priory of Godstow, where the gentle nuns went about their holy business; and on the opposite bank from the priory there was an inn called the Trout.

This fairy-tale opening announces that we are in the hands of a tale spinner, one who can mingle the familiar with the strange, set a scene, be patient, tell us what we need to know, and withhold what we want to know—namely, who’s at the Trout, and what is the nature of the contrast between that person and the virtuous nuns? Like Malcolm’s canoe, the sentence is formed with care, beautifully engineered to do precisely what it should; it is also floodlike, with a momentum, flow, and rhythm that flicks the reader along. Studying Pullman, whether in The Golden Compass or La Belle Sauvage or his delicious quartet of London mysteries, reacquaints you with the muscular, bodily pleasures of narrative. It is no wonder, then, that he has fashioned for himself a kind of poetics of embodiment, and that his best invention, the idea of the daemon, succeeds in part by turning spiritual abstractions literal. Pullman excels at concretizing evocative notions (self-consciousness, for instance, or how the self experiences its own contradictions) in witty dialogue between a child and his animal-shaped soul mate.

Daemons have always been one of the most irresistible features of Lyra’s universe. Their mythology only deepens in The Book of Dust. Did you know that, while young, they can mix and match attributes? Early on, Asta tries to “become an animal that didn’t yet exist,” but “the best she could do so far was to take one animal and add an aspect of another, so now she was an owl with duck’s feathers.” Pullman’s mutable imagination never finishes generating, rolling, foaming. In an interview with Slate last year, he told me that his hypothetical creaturely companion would assume the shape of a crow, raven, or magpie—a bird that “digs around for shiny, bright things and steals them.” But with La Belle Sauvage, the author hasn’t just stitched together sources, or glued whimsical new features atop a young adult template. This is a book rooted in elemental forces: earth, water, and fire. Its pages house a living soul.

—

The Book of Dust: La Belle Sauvage by Philip Pullman. Knopf Books for Young Readers.