Every critic knows that readers love a spirited hatchet job, whether or not the author being chopped is one whose work they’ve hated—or even read. Much of the public seems to possess an ambient belief that the literary world is filled with frauds and self-styled geniuses whose reputations have been propped up by venal publishers and the reviewers who toady up to them. In this light, anyone who dares to challenge the allegedly phony consensus by ripping apart one of the unjustly elect gets hailed as a hero. Every so often, a particularly harsh review will prompt an outcry; recently this happened after William Giraldi’s slashing, in the New York Times Book Review, of two books by the relatively unknown novelist, Alix Ohlin, whom he damned for embracing “the bland earnestness of realism.” But Ohlin was small fry, and much of the outrage Giraldi’s review ignited—he was accused on Twitter of failing to perform a critic’s basic duties and of producing a “pretentious, vicious and self-regarding” piece of work, among other offenses—seemed to arise from the sense that he was an insufferable blowhard while she was nice, or at the very least, harmless.

Yet surely sometimes a hatchet job is called for. The target needs to be big enough, as when David Foster Wallace, in 1997, eviscerated John Updike as emblematic of a band of “Great Male Narcissists” who flourished in the mid-20th century. (The two others were Norman Mailer and Philip Roth.) Wallace’s case against Updike claimed moral weight; the novelist, he argued, while a ravishing stylist, was a “solipsist” who endlessly embroidered the “joyless and anomic self-indulgence of the Me Generation.” Wallace made himself the spokesman for a younger cohort picking its disconsolate way through that generation’s stained and sordid leavings.

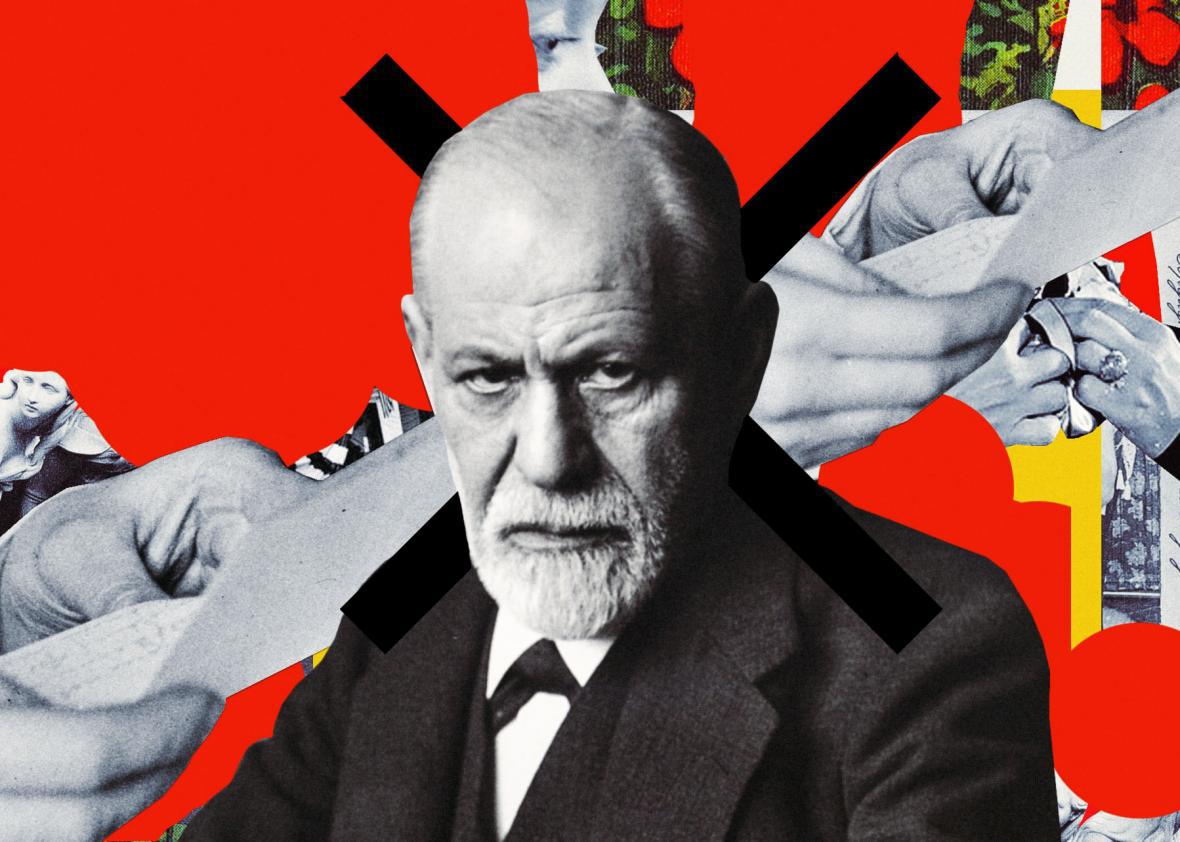

And then there are those authors who pose a genuine threat to the public welfare. That’s how Frederick Crews, distinguished literary critic and professor emeritus of English at the University of California at Berkeley, views Sigmund Freud. Crews is a shrewd, puckish, incisive writer, particularly when it comes to the excesses of his fellow academics. In the ’60s he published a best-seller, The Pooh Perplex, that parodied the most popular strains of literary criticism at the time by applying them to A.A. Milne’s bear of very little brain. (A sequel, Postmodern Pooh, published in 2001, deftly updated the exercise to account for the latest theoretical developments.) But for the past 20 years, Crews has been largely occupied, both between hard covers and in the pages of the New York Review of Books, with dismantling the reputation of Freud and with debunking what he views as one of the most dangerous manifestations of the psychoanalyst’s legacy: recovered memory therapy. His new book, Freud: The Making of an Illusion, is the culmination of this campaign, 700 pages of closely argued indictment intended to definitively bury what Crews regards as the myth of Freud as an innovative and insightful thinker. By the time he’s done, the legendary Viennese doktor has been reduced to not much more than a rag, a bone, and a hank of hair.

Crews goes gunning for two distinct Freuds: the doctor/scientist and the man. The former, as Crews acknowledges, has suffered a steep fall in reputation over the past 45 years. The biological model on which psychoanalysis was based has been superseded by newer discoveries, particularly in neurochemistry. Freud published the works that would establish his reputation as a savant of humanity’s unacknowledged inner life in the early 1900s; over the subsequent century, it has become ever harder to ignore the lack of empirical evidence for the effectiveness of psychoanalysis as a therapy. Our growing understanding of the complexity of consciousness and the dizzying variety of human experience makes Freud’s rigidly universal model of the unconscious and its drives—from the Oedipus complex to penis envy—seem laughable, blinkered by his background as a patriarchal, bourgeois 19th-century Viennese.

But to Crews’ annoyance, these erosions haven’t done enough to wear down Freud’s reputation as a bold, original thinker who revolutionized our understanding of the human mind. He knows that nearly all his readers, “believing that Freud, whatever his failings, initiated our tradition of empathetic psychotherapy,” will “judge this book to have unjustly withheld credit for his most benign and enduring achievement.” But Crews will have none of that. Instead, he aims to prove that Freud not only had “predecessors and rivals in one-on-one mental treatment” but that he also “failed to match their standard of responsiveness to each patient’s unique situation.” Whatever is good in psychotherapy, he insists, is due to other pioneers and the psychologists who steered the profession away from Freudian principles after his death.

Without a doubt, Freud was a terrible doctor. Anyone who reads his case histories or has more than a passing familiarity with the real events on which they were based can only pity those individuals unfortunate enough to come under his “care.” As Crews painstakingly documents, using Freud’s own letters and clinical notes (many of which were, until recently, published only in bowdlerized form by his acolytes), Freud disliked medicine, was revolted by sick people, and held his patients in contempt. “I could throttle every one of them,” he once told a shocked colleague. Although he often claimed to have cured people of hysteria, neuroses, or other ailments, those claims were almost entirely false. He helped very few—quite possibly none—of his patients, and spectacularly harmed several.

While Freud’s inadequacy in helping the people who paid him to help them frequently gets treated as an unfortunate footnote to an otherwise brilliant career, Crews aims to carry the observation further. Freud was a bad doctor, he argues, because he was a bad scientist and furthermore a weak and unethical man. Crews’ Freud is first and foremost dishonest, misrepresenting his past, his data (when he bothered to collect it), his results, his patient’s life stories, the contributions to his theories by friends and colleagues. Animated by “a temperament and self-conception” that “demanded that he achieve fame at any cost,” Freud concocted theories about the human psyche based on his own idiosyncratic past and personality and attempted to force his patients to corroborate them. He pressed them to confirm the often preposterous suppressed “memories” he claimed to have deduced from their symptoms and, when they stood firm, interpreted their very resistance as confirmation. (Many of his early, and therefore least awestruck, clients laughed outright in his face, or even parodied his more bizarre scenarios.) He hero-worshipped a series of male mentors and collaborators, ignoring their shortcomings to the detriment of their patients (who were sometimes his own), then turned on them later, often viciously. He was an autocrat who bullied his wife, compelling her to choose between him and her family, then cheated on her with her own sister. He set up psychoanalysis as a self-enclosed, self-verifying cult of personality, playing his followers off against each other to safe-guard his own supremacy. All these claims Crews backs up in exhaustive detail: If Freud had so much as stiffed a waiter and left a record of it, you’d find it in Freud.

None of this automatically invalidates everything Freud wrote or said. Many bona fide geniuses are dreadful people who mistreat those around them and cut corners in their professional lives. Both Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Bob Dylan have plagiarized, yet both are still brilliant. A proper hatchet job—and that is exactly what Freud is—should be directed at a tall tree, preferably one that towers, or at the very least looms. But it takes a lot of muscle to fell such a tree, and that sometimes includes ugly details from the subject’s personal life. Crews maintains that all of the transgressions he documents are relevant to his case against psychoanalysis. Freud made arguments that he claimed, falsely, were based on real-world observation. He pretended to have cured patients who showed little improvement or actually got worse. He presented himself as a scientist without meeting even the modest standards of late-19th-century empirical rigor. His personal problems (homoerotic crushes, impotence, cocaine abuse) affected his work because he insisted on projecting them into theories that he applied to everyone. And those theories affect the real lives of many people.

Nevertheless, a hatchet job is always at risk of being read as evidence of a vendetta, motivated by a suspiciously personal dislike or rivalry. Wallace’s takedown of Updike has been called “Oedipal,” so picture how thick and fast the Freudian interpretations fly when the target is Freud himself. He is the figure most closely associated with the idea that people don’t always understand their own motives, especially when they pursue seemingly trivial goals with great passion.

It must be exasperating for Crews to have his vehemence again and again greeted with raised eyebrows and a nudge to the reader’s ribs. “Paraphrasing Voltaire,” wrote the historian George Prochnik in a recent review of Freud, “if Freud didn’t exist, Frederick Crews would have had to invent him. In showing us a relentlessly self-interested and interminably mistaken Freud, it might be said he’s done just that.” In other words: Surely an animus so implacable makes the critic untrustworthy? Crews justifies his zeal by extending his attacks to the quasi-Freudian recovered memory therapy—a practice that is already discredited and banished from the DSM-V—as well as the general notion that our psyches are shaped by traumatic memories to which we have no conscious access. There will always be a few diehard believers in psychoanalysis and practitioners of bogus derivative therapies to push back against Crews’ crusade, and they give Crews a rationale to persist. Freud’s reputation isn’t trivial, but then neither is Crews’ career, and a lover of cogent, witty literary criticism could be forgiven for wishing that Crews had more often found other themes to write on over the past two decades.

Yet the missed opportunity of Freud isn’t Crews’ refusal to scrutinize his own motivations in damning Freud. It’s not even obvious, as Prochnik seems to believe, that his scorn is over-the-top. On occasion in Freud, Crews touches on the most fascinating aspect of Freud’s reputation: why he still retains the image of a seminal thinker when he doesn’t seem, after all, to have earned it. In his preface, Crews lists some of the cultural waves Freud fortuitously caught, from “a backlash against scientific positivism” to a “waning of theological belief.” Later, in one of the book’s most intriguing chapters, he notes how Freud patterned his case histories after Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, crafting his notes into “cunningly plotted works that create and then resolve suspense.” Alert readers of this review might be wondering if it makes sense to liken a hatchet job on a novelist like Updike to an assault on a thinker, like Freud, who made claims of fact. But Crews insists that psychoanalytic theory is not science, but fiction, and that Freud’s literary prowess is precisely the secret of its success.

According to Crews, Freud’s sense that psychoanalysis would rise and fall on the quality of the stories it told extended to his own autobiography, which he presented as a “serial adventure of the intellect” pursued by a lonely, Promethean hero. This yarn, fused with psychoanalytic theory itself, became one of the dominant intellectual fictions that presided over the heyday of Updike’s career. Furthermore, Crews accuses Freud of the same primal sin—an inability to see beyond himself and his own interests—that Wallace levels against Updike. This, surely, is no coincidence. These narratives have endured for so long because so many people prefer them to the truth. Why? That’s a question Crews touches on in Freud, but only lightly. If the book fails, it is not in pressing its cause so fiercely but in mistaking who deserves the lion’s share of his scorn. The best hatchet jobs don’t just assail an author or thinker for shoddy or disingenuous work. They also indict the rest of us for buying in.

—

Freud: The Making of an Illusion by Frederick Crews. Metropolitan Books.