John Ashbery was the poet who observed that “it’s different when you have hiccups.” He was right about this—right about many things, even if his fabled “difficulty” sometimes obscured the felicity of his intuition. In the same poem, called “Thrill of a Romance,” he wrote that “everyone’s solitude (and resulting promiscuity)/ perfumed the byways of villages we had thought civilized./ I saw you waiting for a streetcar and pressed forward./ Alas, you were only a child in armor.”

I confess I am not sure what Ashbery, who died Sunday at 90, is getting at here. That’s his game: lines so precise and unusual that they must mean something, a kind of intricate nonsense that settles in your body like sediment. And yet—can you imagine anything less civilized than the indignity of having the hiccups alone, with no one to laugh with you or slap your back or offer up one of those ridiculous old wives’ cures (like rubbing the roof of your mouth with a Q-tip)? Maybe solitude makes us weak and childlike. But Ashbery is too mischievous for thesis statements.

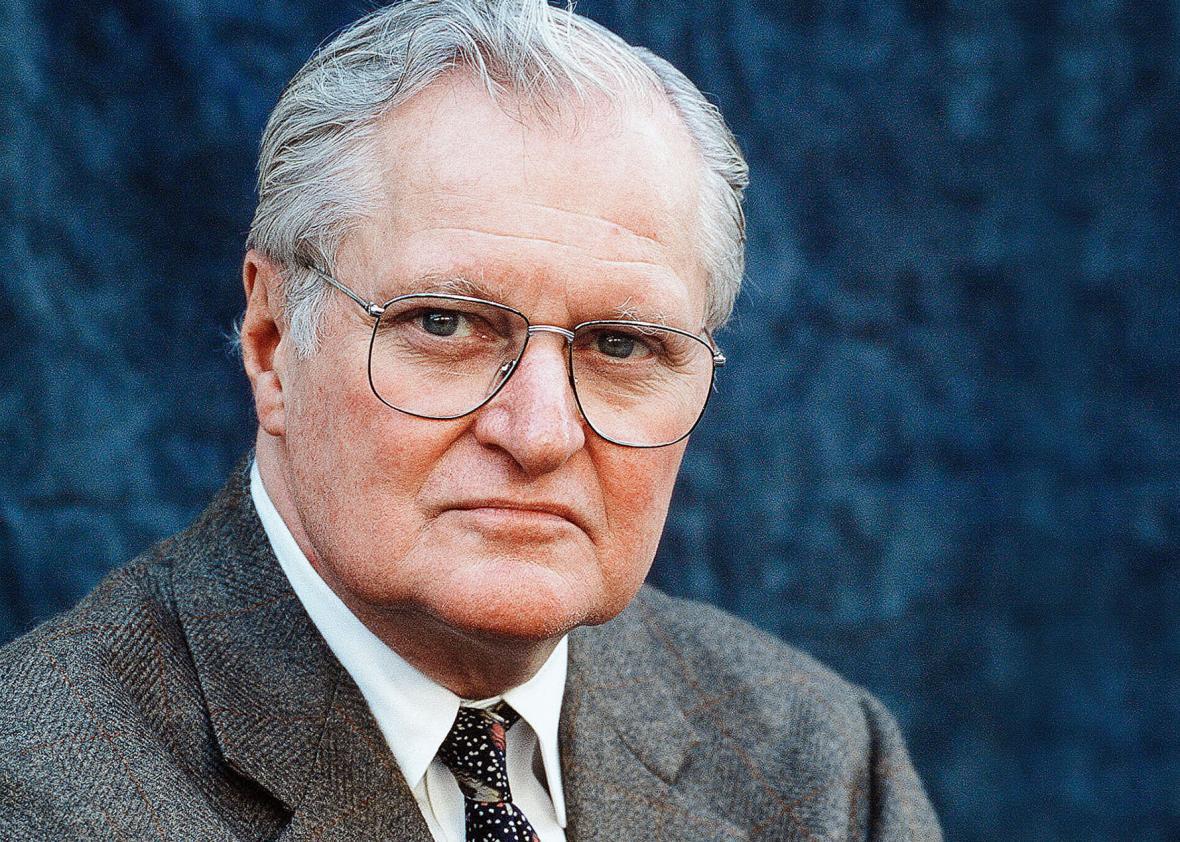

His life, documented in any number of beautiful tributes winging into the papers this weekend (I especially loved this one from David Orr and Dinitia Smith), feels in some ways divorced from his poetry, which is abstract and often subjectless. Ashbery—a Harvard grad associated with the New York School—made his voice into plural voices, and forced them to babble in languages we hardly understood. Most of his pronouns were red herrings. Mashing together slang, jargon, pressurized lyricism, erudition, and singsong, he was often seen to court impenetrability in his search to conjure emotional textures rather than solid ideas. His aim, as Meghan O’Rourke reported in her wonderful primer (he is the type of artist to require a primer), was “to produce a poem that the critic cannot even talk about.” Of course, the critics talked anyway. An essay in the Saturday Review complained that Ashbery’s esoteric phrases contained “about as much poetic life as a refrigerated plastic flower.” A New York Times reviewer snarked, “I actually thought I was going to burst into tears of boredom.”

This critical resistance was understandably a source of sadness for Ashbery. Asked by an NPR interviewer in 2005 whether his poems were “accessible,” he replied ruefully, “Well, I’m told that they’re not.” But, he added, they are “about the privacy of all of us, and the difficulty of our own thinking. … And in that way, they are, I think, accessible if anyone cares to access them.”

What does it mean to “access” a poem? We often speak of art that “captures” things, by which we mean that it makes some progress toward naming the never-before-named or catching some echo of the inexpressible. But instead of locking feelings in cages, Ashbery went around opening hatches. His poems’ meanings were always running away, leaving footprints that were alluring and funny and hard to parse. For that reason, I often found Ashbery’s work, rather than repellent or obscure, weirdly inclusive, in the sense that I didn’t think other people understood it any better than I did. (Of course, that’s a hilarious illusion, tons of readers understand Ashbery better than I do, don’t @ me.) “The room I entered was a dream of this room,” he writes in “This Room.” “Something shimmers, something is hushed up.” In the midst of not understanding Ashbery, the Ashbery reader discovers a few gestures or images to toy with. She sees a glint before it’s gone. She feels the vibrations of the song within the soundproofed box.

I do not mean to characterize him as a poet of lazy sparkle or fluttering veils. Ashbery’s oeuvre obeys a rigorous logic; that logic simply happens to mystify most human beings on the planet. O’Rourke suggested that he wants to convey “how the barrage [of language and experience] affects a mind haunted by its own processes.” Mark Ford called him “a restless, supremely sophisticated imagination meditating self-reflexively on experience.” Writing in the New Yorker, Larissa MacFarquhar was taken by his comparison of poetry to music.

Ashbery may be best known for “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” an elusive consideration of the Parmigianino painting that spirals into a 15-page magnum opus about perception, art, and consciousness. The mirror in the title retains an image of reality at once familiar and curious. It is (I guess?) a metaphor, but one that resists definitive unpacking. “One feels too confined,” Ashbery writes, “… and each part of the whole falls off/ and cannot know it knew.”

Such a feeling of confinement resonates circa 2017. The country is swimming in a discourse that privileges 140-character arguments and a herd mentality. We hate nuance, rebelling against anything that confuses us. I fear, even without Ashbery’s loss, that we can’t handle a convex mirror. We’d just shout that its take is garbage.

But it is not. Ashbery’s poems—cerebral and spectral, equal parts brain and spirit—refuse to summon a mimetic picture of the world; instead, they enact a line of thought, a needle trailing its thread of meaning. The poetry may be difficult, but I’m not convinced we need to understand the fiber that knits us up. Or, rather, we should give ourselves the credit that John Ashbery did. We understand more than we think.