One day in the early 1890s, an Osage Native American took a local trader out to see a rainbow slick on the tribe’s territory in what is now northeastern Oklahoma. The Osage dipped a blanket in the creek, wrung it out into a container, and the trader hustled the sample back to the town of Gray Horse, where he confirmed his guess: It was oil.

Around 30 years later, in May of 1921, two bodies were discovered by chance in separate locations on the reservation. Charles Whitehorn, 30 years old, and Anna Brown, 34, both members of the tribe, had been shot dead and abandoned—Whitehorn in the brush at the base of an oil derrick and Brown by a creek at the bottom of a ravine.

The connection between the rainbow on the water and the murders of Whitehorn, Brown, and many other members of the Osage tribe is laid out to devastating effect in Killers of the Flower Moon, the latest work of narrative nonfiction by David Grann, New Yorker writer and author of The Lost City of Z and The Devil and Sherlock Holmes. Grann’s singular skill is to find a story that, while not unknown, is not known enough, and to dig so deeply and precisely into the historical record that what he finds not only amplifies and builds upon that record but arrives with the force of revelation. This is a book that may significantly alter your view of American history. It did mine. Like Grann himself, I found myself wondering why I had never learned till now of the strange and terrible saga that came to be known as the Osage Reign of Terror.

On one level, the story of the tribe’s experience in the 19th century is distressingly familiar. The Osage agreed to promises and treaties that the U.S. government refused to honor, lost nearly 100 million acres in the Great Plains, and were forced to find a new home in the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, buying 1.5 million acres from the Cherokee in the 1870s. The great irony is that tribal leaders chose this land precisely because it was bleak and unfarmable (“a big pile of rocks,” as one chief memorably put it), with nothing to draw white settlers’ further interest in Osage territory.

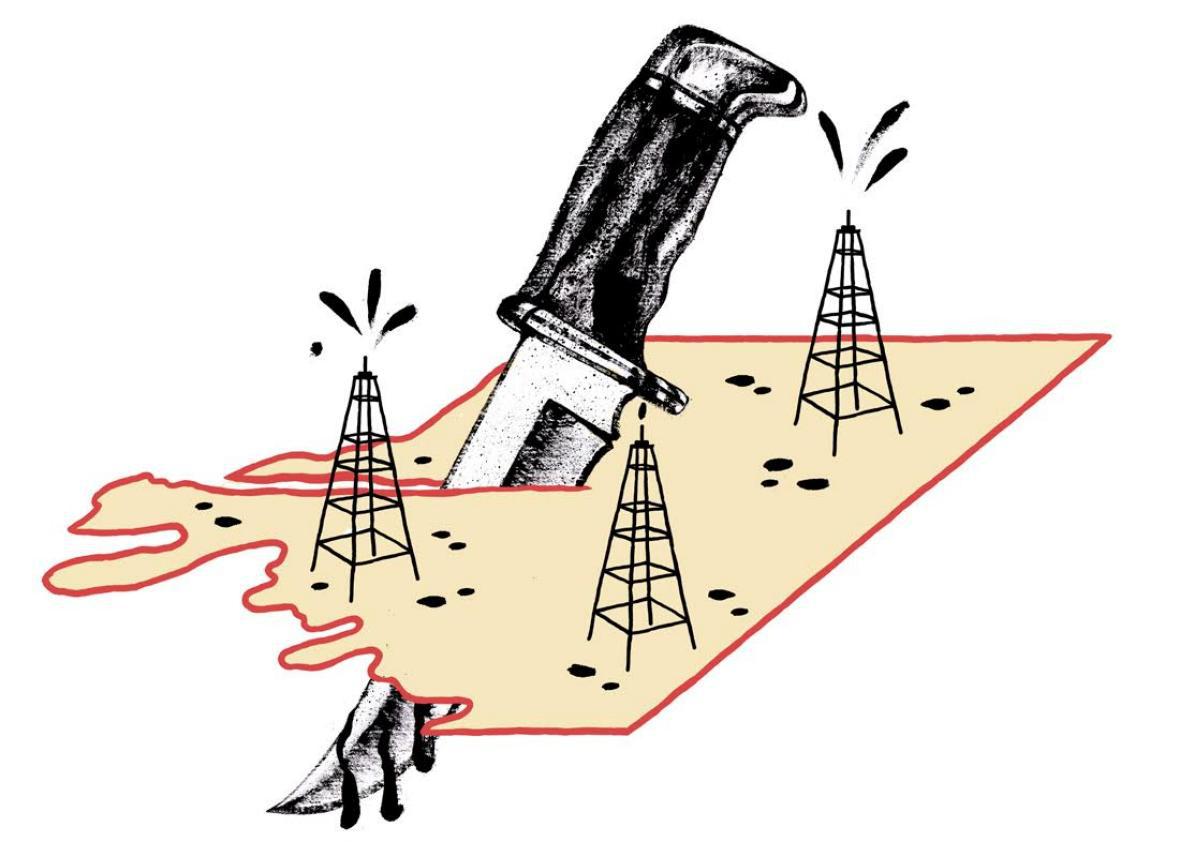

The discovery that the reservation held some of the biggest oil deposits in the United States, of course, changed all that. By the 1920s, having with some foresight retained tribal ownership of oil and mineral rights, the Osage had become wealthy beyond most people’s dreams. They bought houses and cars, hired chauffeurs and private planes, kept servants—in short, did whatever people with money do. Fortune-hunters, outlaws, financiers, and other opportunists turned the reservation towns into hives of commerce, avarice, and speculation. Inevitably, the fortunes of the Osage drew national attention. “Lo and behold!” said a story in one New York weekly. “The Indian, instead of starving to death … enjoys a steady income that turns bankers green with envy.” A report in Harper’s struck a more ominous note: “Every time a new well is drilled the Indians are that much richer. The Osage Indians are becoming so rich that something will have to be done about it.”

It was against this boomtown backdrop that the murders took place. There was no single method and no clear motive. Nor were the killings confined to the reservation. The Osage and their allies were shot, poisoned, bombed, drugged, stabbed, and thrown from a train. A wealthy white oilman who went to Washington seeking a federal investigation was abducted and killed on the night he arrived. Another man with similar aims was gunned down in Oklahoma City. By the summer of 1923, the official death toll had reached two dozen, and an Oklahoma reporter wrote, “The perennial question in the Osage land is, ‘Who will be next?’ ” And where was law enforcement while all this was going on? A good question. A veritable org chart of ostensible crime-solvers—justices of the peace, sheriffs, private eyes, state investigators, federal agents—waded in and out of the case, unable or unwilling to produce a prosecution or even a credible suspect. (Initial inquests on the murders of Brown and Whitehorn wrapped up by concluding that both had died “at the hands of parties unknown.”)

What makes Killers of the Flower Moon so compulsively readable is Grann’s ability to draw characters from the pages of history and give them the aura of living, breathing humans. Take Mollie Burkhart, a sociable Osage woman in her 30s, eager to keep tribal tradition alive, who withdraws into silence and fear as her family members die around her. Or William Hale, Mollie’s uncle-in-law, a former cowboy of mysterious origin who has refashioned himself as a gentleman rancher and political player, “the King of the Osage Hills.” Yet no character’s entry into the narrative surprised me more than that of a “boyish” J. Edgar Hoover, the recently named director of the Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI), which had been created by Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 to investigate an odd lot of crimes including antitrust violations, federal prisoner escapes, “the interstate shipment of stolen cars, contraceptives, prizefighting films, and smutty books,” and crimes on Indian reservations. Hoover had once tried to shuttle the Osage case back to state authorities, but in 1925, with pressure mounting, and given the bureau’s bungling of an initial foray into the investigation, Hoover sensed a scandal coming. He turned to Tom White, a former Texas Ranger who ran the bureau’s Houston office, wore a suede Stetson, and had, Grann writes, “the sinewy limbs and eerie composure of a gunslinger.”

Killers of the Flower Moon has been aptly described as cinematic, and assuming that a movie is made of the book (Scorsese, DiCaprio, and De Niro are said to be interested), a likely set piece will be the gathering in Osage County of the largely undercover team put together by Special Agent White. This team includes a former New Mexico sheriff who poses as a quiet, elderly cattleman; a deep-cover operative and former insurance salesman who takes on the role of, well, an insurance salesman, visiting suspects’ homes and pushing actual policies; and a Native American agent—on thin ice with Hoover’s bureaucratic bureau for not filing reports—whose cover is that of a medicine man looking for his relatives.

Early on, Grann describes the popular conception of the “private eye” as follows: “He found order in a scramble of clues and, as one author put it, ‘turned brutal crimes—the vestiges of the beast in man—into intellectual puzzles.’ ” Grann’s profound achievement in Killers of the Flower Moon is to construct the intellectual puzzle with infinite skill while never losing sight of the human impact of the brutal crimes against the Osage. There are, from the beginning, clues to the mystery of the killings, but, given Grann’s nuanced characterization and deft interplay of crime story and cultural history, it is often hard for the reader (as it was for the intended victims) to know the guilty from the innocent, to know who to trust and who to fear. Thus we may feel some measure of satisfaction or at least clarity when the federal investigation at long last leads to prosecutions, convictions, and prison sentences. But then comes the final section of the book, when Grann travels to contemporary Osage County to conduct research and speak to the descendants of Mollie Burkhart’s generation. What he finds is what Killers of the Flower Moon has led us to suspect for some time: There is more to the story. What the Osage were facing was not simply a criminal mastermind or gang but something much worse—a “culture of killing” too prevalent to be contained in the files of any known criminal prosecution. The case is not closed, and perhaps never will be, and its legacy of sorrow and uncertainty remains.

—

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann. Doubleday.