For much of its 50-odd year history, the Flintstones franchise has shared a great deal with the vitamins that bear its brand: Both are colorful and innocuous, but neither accomplishes much of note. The original cartoon’s creators seemed to think it was funny enough to juxtapose primitive aesthetics and modern customs. Its world was fundamentally conservative, not just in its gender politics but more generally in its refusal to truly interrogate the norms it held up for laughter.

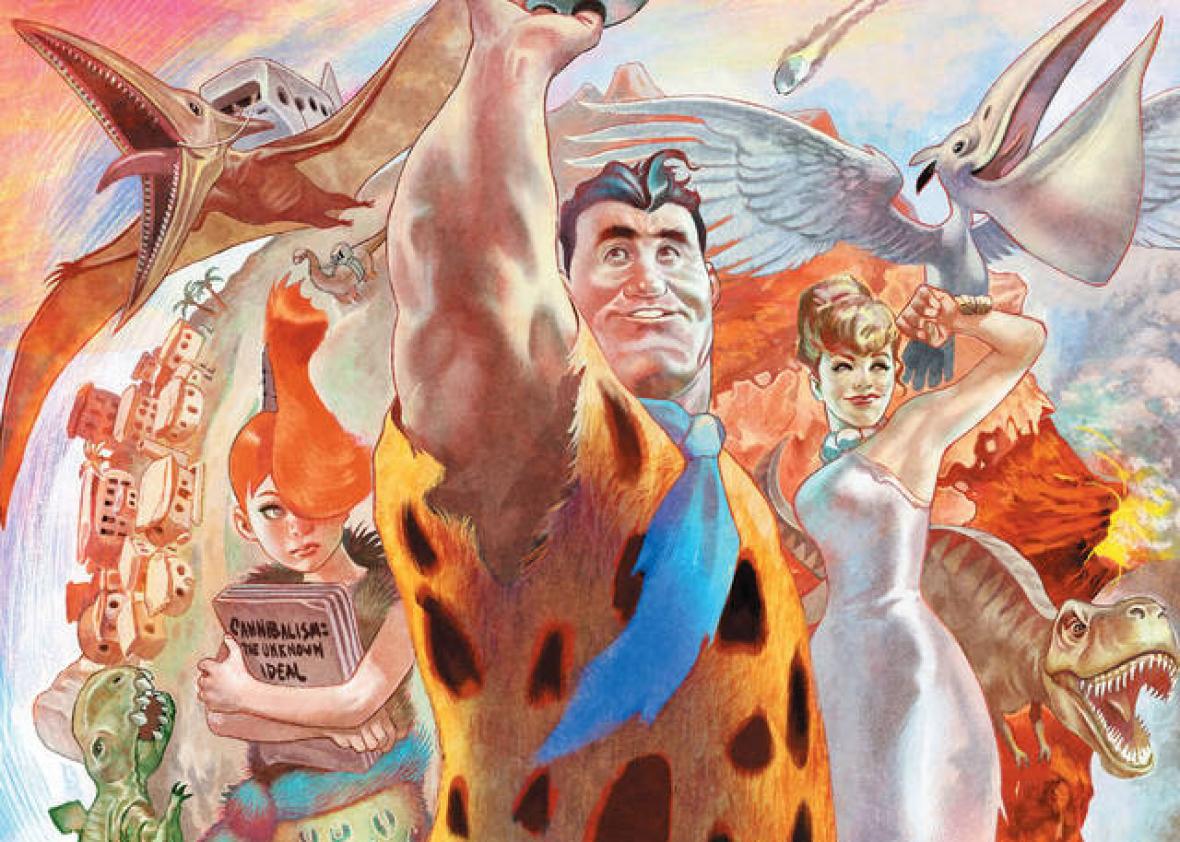

Given this history, it’s hard to imagine how DC’s brilliant new Flintstones comic, the first six issues of which are now available in a single volume, came to be. Written by Mark Russell and drawn by Steve Pugh, and despite bearing Hanna-Barbera’s stamp of approval, the series satirizes the Flintstones universe itself, questioning the easy consolations this series has long provided. It sheathes its titular patriarch with muscles and weighs him down with worldly worries. No longer a mere expression of enthusiasm, “Yabba-dabba-doo” becomes the battle cry of a milieu in which children are routinely carried off from the playground by pterodactyls. And somehow, in spite of all that, it remains a delightful, even charming, read.

Because it’s an episodic series, published in monthly installments, each of the chapters tells a distinct story. Nevertheless, many of the themes the franchise has always embraced—most of all the nuclear family and its discontents—suture these distinct segments together. The comic is rife with details that will be familiar to even the most casual admirers of older, glibber incarnations of the Flintstones. In the third chapter, for example, we meet the Grand Gazoo, a green alien who first joined the television show in 1965. (No mere trickster here, he claims that his title “roughly translates to ‘game warden.’ ”) There are plenty of freshly updated Stone Age puns on offer too: The Flintstones shop at Trapper Joe’s and Tar Pit after caffeinating at Starbrick’s Coffee while teenage rebel Pebbles wears a Nick Caveman T-shirt with cutoff sleeves.

Read as a whole, this new iteration has a satirical bite that the more toothless earlier versions lacked. When it engages in topical parody—say, by satirizing consumerist impulses or electoral politics—it doesn’t feel especially novel or sharp. Instead, such sequences work as emotional snares: Russell and Pugh will spend most of a chapter stacking up dopey jokes about a familiar topic, only to ambush the reader with a sudden shift into unexpected poignancy. Take the fourth chapter, which focuses on gay marriage debates but adds little that feels new apart from a gag in which one of Fred and Wilma’s more conservative neighbors tells the couple, “Go back to the sex cave like nature intended!” If it’s not quite engaging as social criticism, though, that story is more valuable for the surprisingly raw honesty of a moment when Fred, his enormous body filling the panel, confesses that he fears Wilma will one day stop loving him. Much the same is true of the first chapter’s kicker, in which a tepid parody of art world pretensions pivots into a meditation on loss, grieving, and persistence.

None of this would work were it not for the larger context that the history of the Flintstones provides. Russell and Pugh rely on our familiarity with these characters, lulling us into a false sense of comfort that leaves us emotionally exposed. Though the franchise was not solely targeted at children, at least not initially—its earliest seasons aired in prime time and drew on The Honeymooners—the intervening decades have leant it a juvenile patina. These newer stories exploit the expectations of innocence that we bring with us to the series, only to repeatedly pull the saber-toothed tiger pelt out from under our feet, sending us sprawling.

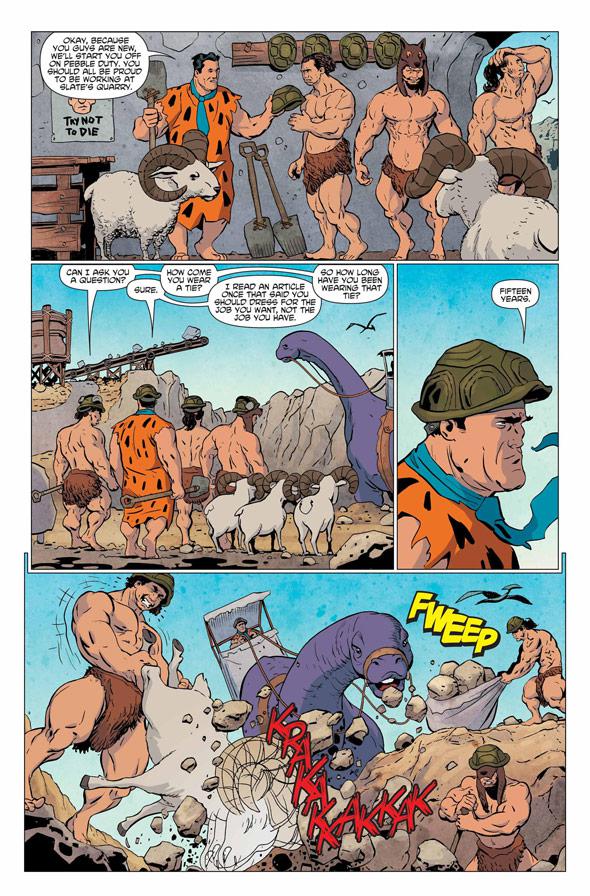

Russell and Pugh are not unique in their willingness to push the franchise in a more mature direction. In the little-loved, John Goodman–starring 1994 film, Fred’s signature blue tie furnishes an infantile erection joke, abruptly coiling upward when our hero meets his seductive secretary. But the comic moves beyond “adult” humor into a darker commentary on real adulthood. In its first issue, that same blue tie serves as a point of curiosity for his fellow quarry laborers. “I read an article once that said you should dress for the job you want, not the job you have,” he explains, shovel in hand, turtle-shell hardhat planted squarely on his head. And how long has he been dressing that way? a co-worker asks. “Fifteen years,” he responds, his face a stony mask.

DC Comics

We also gradually learn the details of Bedrock’s founding. Though the cartoon’s closing credits famously promised “a gay old time” in the town, Russell and Pugh give it a grimmer backstory, one built on a legacy of genocide and exploitation. That narrative plays out most tenderly in the revised origin story of Bamm-Bamm. Early in the Goodman film, Fred Flintstone clears out his family’s hard-earned savings to help Barney and Betty adopt the feral child. It’s a reckless act, but one that Wilma quickly forgives on grounds of its basic goodness. In the original series, Bamm-Bamm’s first appearance was still more innocuous: His parents found him abandoned on their doorstep and took him in after a brief legal tussle. The less said about his latest incarnation the better—though it resembles the earlier versions, it’s a story well-worth reading for the particular way it unfolds—but suffice it to say that we learn his very existence is a grim (yet somehow also joyful) reminder of the sins Bedrock’s residents committed along the way to building their world.

The realistic quality of Pugh’s art—coupled with Chris Chuckry’s richly shaded coloring—at once underscores and beautifies this pervasive melancholy. The original Hanna-Barbera cartoon was broad in every sense, with heavy lines delineating the bodies of its sparsely animated characters. That exaggerated visual aesthetic carried over into its sense of humor: The show’s protagonists were quick to emotional extremes, vacillating between anger and adoration according to the comic demands of a given scene rather than the dictates of their underlying personalities. In this sense, the subtler qualities of Pugh’s art are revealing, driving home Russell’s willingness to humanize his protagonists, despite the madcap chaos that always chases them.

The new book’s most disquietingly blurred line comes in its treatment of the Bedrockians’ animal companions. As in the original stories, some are beloved family pets, but most serve more functional purposes: Quarry boss Mr. Slate’s couch is a giant sloth, an octopus washes the Flintstones’ dishes, and dinosaurs are construction equipment.* But Russell and Pugh also imbue these creatures with varying degrees of sentience, letting them contemplate their menial place in the world. We occasionally glimpse them huddled together after the Flintstones head out for the night, celebrating the thought that they might finally be free from the cruel and arbitrary tasks our heroes assign them.

In one especially memorable sequence of scenes, a pair of those animals—Fred’s armadillo bowling ball and his family’s adorable baby elephant vacuum—forge an unlikely bond. As the two bemoan their miserable lot in life, Vacuum acknowledges that he takes comfort in their relationship as he whiles away his days in a dark closet. “Knowing that my friend Bowling Ball is on the other side of the door. It makes me think. Maybe the only meaning to life is that which we get from each other,” he says.

There’s an unavoidable pathos to these lines, even coming as they do from a diminutive purple elephant. They speak to the improbable uplift of Russell and Pugh’s series, which sometimes flirts with existential terror but never embraces the old Sartrean maxim that hell is other people. Here instead, other people are all that our characters have, whether they’re anticipating extermination by meteor or grappling with infertility. What emerges is a story about the profound fragility of civilization—but also about the unlikely durability of the human connections that make it up.

—

The Flintstones, Vol. 1 by Mark Russell and Steve Pugh. DC Comics.

Read all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

*Correction, April 12, 2017: This sentence originally misstated that Philip is Mr. Slate’s sloth. Philip is his turtle. (Return.)