A few chapters into Universal Harvester, you might be forgiven for thinking you were reading an unusually artful novelization of some forgotten X-Files episode. John Darnielle—front man of the Mountain Goats and author of the National Book Award–nominated novel Wolf in White Van—opens his story in a Nevada, Iowa, video store, a shop that, like the town itself, is poorly weathering the final years of the 20th century.* One day, a customer returns a tape, telling the clerk, Jeremy, that there’s something on it, something wrong with it. Soon after, Jeremy hears similar news from another nonplussed regular. Hesitant at first, he begins to investigate.

Jeremy’s findings trouble and fascinate him in equal measure. Inexplicable sequences have been spliced into otherwise innocuous films. The tapes begin as usual, run for a bit, and then without warning, everything changes: Here a hooded figure poses awkwardly in an ill-lit barn. There bodies writhe under a tarp, fingernails scraping against canvas. And in one, a woman (is it Jeremy’s dead mother?) runs from the camera and disappears into the distance. Uncanny in the Freudian sense—alienating precisely because they are familiar—these are images that should not exist, least of all on an otherwise innocuous She’s All That cassette.

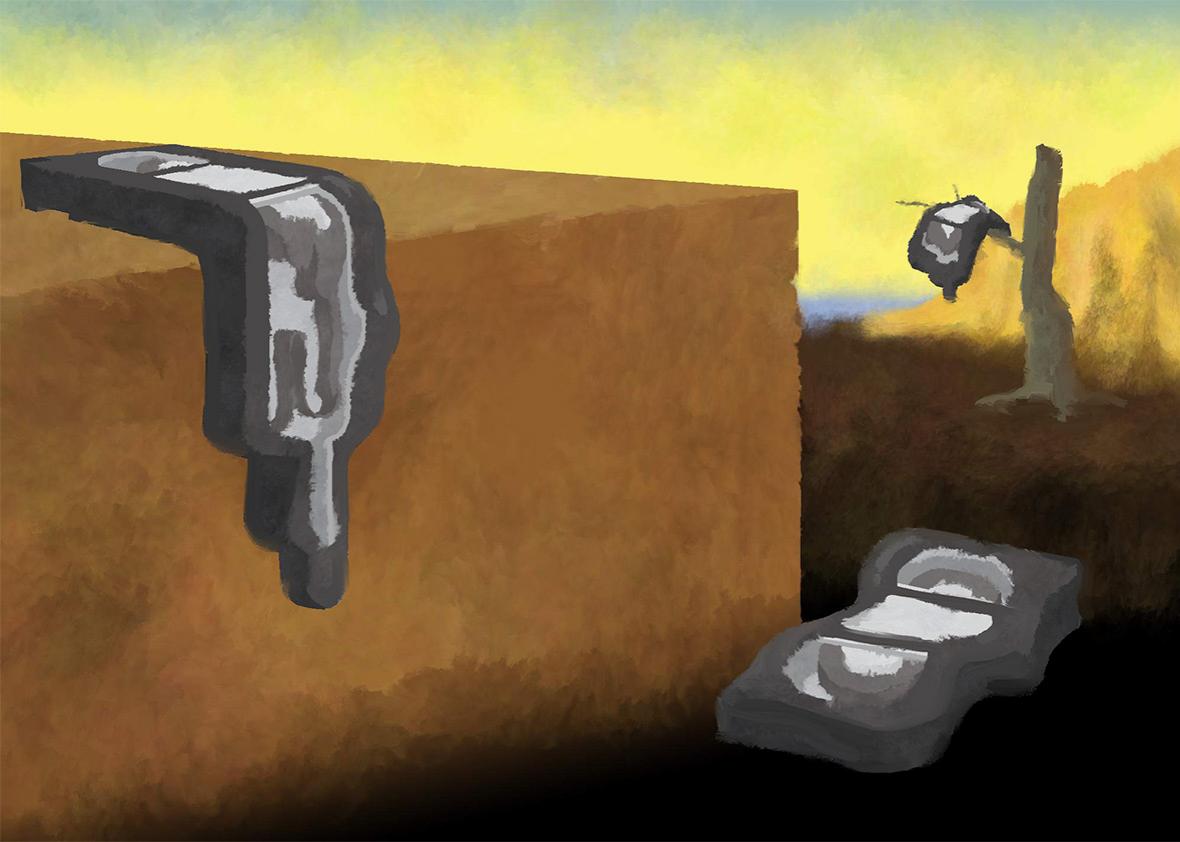

Most of those who glimpse these clips are similarly troubled and similarly fascinated. Studying them becomes an obsessive project: People print out frames, seeking patterns in the grain of these low-resolution images. You have the sense that Darnielle’s protagonists are being pulled toward or into something monstrous, something otherworldly. But then, much as they sometimes did on the X-Files, all those eldritch implications simply dissolve, replaced by more quotidian revelations. If our characters are tortured, it’s only by the pains they’ve already known.

Personal tragedy has a way of imbuing objectively small concerns with a sense of cosmic import. Fittingly, then, Darnielle’s novel ultimately proves itself to be an exploration of—if not quite a meditation on—the experience of loss writ large. Though Universal Harvester sometimes teases true horror, that promised menace never quite materializes. Instead, Darnielle’s novel belongs to what might be called the literature of disquiet, a sentiment that emerges as much from his syntax as from the content of his story.

Notice, for example, his narrator’s carefully managed shifts in and out of the first person. Much like the sequences someone has spliced into the cassettes, the narrator appears suddenly and unexpectedly, only to vanish again. In one early scene, it manifests in order to theorize about why Jeremy’s co-worker won’t buy a new car. “Farm kids are like this, I’ve found. They don’t like throwing useful things away,” it says. In another, before anything has gone wrong, it ominously skips forward in time to tell us that it has reviewed police records, finding that no one reached out to the authorities until much later when “new people were involved—strangers; variables from the cloudy distant future. The one thing you can never plan for, Mom used to say. Unexpected guests.”

As we eventually learn, this is a presence with a life of its own—and the scars to show for it. Such narrative intrusions are like spirit visitations from a still-living stranger, upending the seemingly easy, familiar order of things in Darnielle’s Iowan locales. Nevertheless, Darnielle and his phantasmagoric narrator share an earthly inclination toward the aphoristic, a sort of wisdom that sits somewhere between the folksy and the philosophical. “A farmhouse has a way of feeling both timeless and impermanent without ever committing to either side,” he writes. “People have expectations of a field: what one ought to be like, how it ought to feel. But a field is what you make of it,” he tells us.

In time, a pattern begins to emerge from these stoicisms, one that tells a quiet story about our estrangement from familiar people, places, and things. “Sometimes you just want to figure out how to fit yourself into the world you already know,” Darnielle writes. If we don’t fit into the world we know, it’s because that world is always changing, with or without us: A Home Depot crops up by the highway, or an old crush moves to California. Home is a treadmill, and powers beyond our control regulate its pace.

Here, the novel’s preoccupation with the VHS tapes that Jeremy rents out takes on a special importance. Unlike the digital, streaming media that would eventually replace it, VHS insisted on its own materiality. A cassette had heft, and inserting it, watching it, rewinding it when you were done left you with the feeling that you were manipulating a physical thing. In the experience, there was a sense of control: Fast as the world might move around you, you could always pause or rewind, watching fragmentary frames skip by. Almost unglued from linear time, Universal Harvester’s narrator sometimes seems similarly adroit—here freezing the moment, there skipping forward, like nothing so much as a viewer revisiting a familiar scene.

The freedom of VHS was, of course, illusory. Where the medium promised mastery over time, it too was subject to the relentless movement of history, gradually slipping into irrelevance as other, more convenient technologies replaced it. This may be why the scenes edited onto the tapes at Jeremy’s store unnerve those who glimpse them: Whatever their content, they remind us that our efforts to pull back on the reins of time are always futile, most of all because other forces inevitably pull us along.

Jeremy knows this all too well, and Darnielle suggests that his readers do too. “Bracing yourself against the possibility of disaster came naturally to him,” Darnielle writes. It’s a purposefully awkward phrase, one in which “yourself” implicates us in the novel’s vanishing small town world, too. That feeling only intensifies when the novel more directly implicates the reader in its narrator’s perspective: Describing the journal that one character kept after the death of his wife, that voice explains, “You or I, finding ourselves in Steve Heldt’s shoes, might fill this book with intricate reckonings of our grief, trying to empty ourselves of its burden.” With this, the narrator’s presumption to know how we might respond offers ambiguous comfort. No fortress against sorrow, it at least acknowledges that we’ve all lost something.

If Universal Harvester is ultimately a horror novel at all, as it initially seems to be, it is one in which the only monster is the deep well of our shared sadness. Layers of loss accumulate throughout: Of the media we enjoy, of the communities we grew up in, and, most of all, of the people we love. “It’s in the nature of the landscape to change, and it’s in the nature of people to help the process along,” Darnielle writes in the book’s final chapter. That truth resonates on every page, chased only by the consolatory possibility that we might endure our grief together.

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Read all the pieces in the Slate Book Review

*Correction, March 9, 2017: This article originally misidentified Darnielle’s novel Wolf in White Van as Wolf in a White Van. (Return.)