From the book Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries, available now. Copyright 2017 by Kory Stamper. Published by arrangement with Pantheon, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

It was 2001, three years into my tenure as a writer and editor of dictionaries at Merriam-Webster. There were about 20 of us lexicographers working on revising the Collegiate Dictionary for its eleventh edition. We had just finished the letter S.

By the time that last batch of defining and its citations—snippets of words used in context—for S had been signed back in on the production spreadsheet, the editors were not just pleased; we were giddy. You’d go to the sign-out sheet, see that we’re into T, and make some little ritual obeisance to the moment: a fist pump, a sigh of relief and a heavenward glance, a little “oh yeah” and a tiny dance restricted to your shoulders (you are at work, after all). Sadly, lexicographers are not suited to survive extended periods of giddiness. In the face of such woozy delight, the chances are good that you will do something rash and brainless.

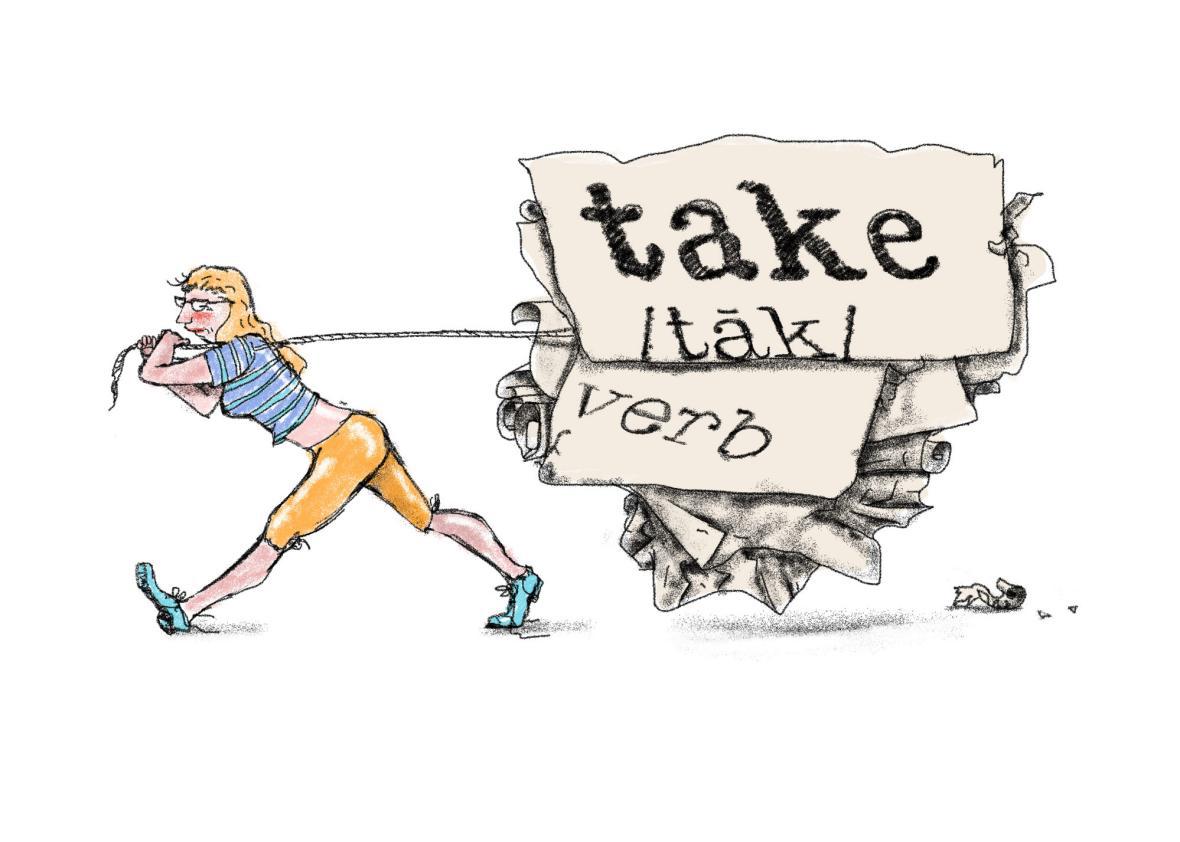

Unfortunately, my rash brainlessness was obscured from me. I signed out the next batch in T and grabbed the printouts of the entries I’d be revising for that batch along with the boxes—two boxes!—of citations for the batch. While flipping through the galley pages, I realized that my batch—the entire thing—was just one word: “take.” Hmm, I thought, that’s curious.

Lexicography, like most professions, offers its devotees some benchmarks by which you can measure your sad little existence, and one is the size of the words you are allowed to handle. Most people assume that long words or rare words are the hardest to define because they are often the hardest to spell, say, and remember. The truth is, those are usually a snap. “Schadenfreude” may be difficult to spell, but it’s a cinch to define, because all the uses of it are very, very semantically and syntactically clear. It’s always a noun, and it’s often glossed, because even though it’s now an English word, it’s one of those delectable German compounds we love to slurp into English.

Generally speaking, the smaller and more commonly used the word is, the more difficult it is to define. Words like “but,” “as,” and “for” have plenty of uses that are syntactically similar but not identical. Verbs like “go” and “do” and “make” (and, yes, “take”) don’t just have semantically oozy uses that require careful definition but semantically drippy uses as well. “Let’s do dinner” and “let’s do laundry” are identical syntactically but feature very different semantic meanings of “do.” And how do you describe what the word “how” is doing in this sentence?

It’s not just semantic fiddliness that causes lexicographical pain. Some words, like “the” and “a,” are so small that we barely think of them as words. Most of the publicly available databases that we use for citational spackling don’t even index some of these words, let alone let you search for them—for entirely practical reasons. A search for “the” in our in-house citation database returns over 1 million hits, which sends the lexicographer into fits of audible swearing, then weeping.

To keep the lexicographers from crying and disturbing the people around them, sometimes these small words are pulled from the regular batches and are given to more senior editors for handling. They require the balance of concision, grammatical prowess, speed, and fortitude usually found in wiser and more experienced editors.

I didn’t know any of that at the time, of course, because I was not a wise or more experienced editor. I was hapless and dumb, but dutifully so: grabbing a fistful of index cards from one of the two boxes, I began sorting the cards into piles by part of speech. This is the first job you must do as a lexicographer dealing with paper, because those citations aren’t sorted for you. I figured that “take” wasn’t going to be too terrible in this respect: there’s just a verb and a noun to contend with. When those piles were two-and-a-half inches high and began cascading onto my desk, I decided to dump the rest of the citations into my pencil drawer and stack my citations in the now-empty boxes.

Sorting citations by their part of speech is usually simple. Most words entered in the dictionary only have one part of speech, and if they have more than one, the parts of speech are usually easy to distinguish between—the noun “blemish” and the verb “blemish,” for example, or the noun “courtesy” and the adjective “courtesy.” By the time you’ve hit T on a major dictionary overhaul like a new edition of the Collegiate, you can sort citations by part of speech in your sleep. For a normal-sized word like “blemish,” it’s a matter of minutes.

Five hours in, I had finished sorting the first box of citations for “take.”

* * *

It is unfortunate that the entries that take up most of the lexicographer’s time are often the entries that no one looks at. We used to be able to kid ourselves while tromping through “get” that someone, somewhere, at some point in time, was going to look up the word, read sense 11c (“hear”), and say to themselves, “Yes, finally, now I understand what ‘Did you get that?’ means. Thanks, Merriam-Webster!” Sometimes, in the delirium that sets in at the end of a project when you are proofreading pronunciations in 6-point type for eight hours a day, a little corner of your mind wanders off to daydream about how perhaps your careful revision of “get” will somehow end with your winning the lottery, bringing about world peace, and finally becoming the best dancer in the room.

But nowadays, thanks to the marvels of the internet, we know exactly what sorts of words people look up regularly. They generally don’t look up long, hard-to-spell words—no “rhadamanthine” or “vecturist” unless the Scripps National Spelling Bee is on TV. They tend to look up words in the middle of the road. Some of the all-time top lookups at Merriam-Webster are “paradigm,” “disposition,” “ubiquitous,” and “esoteric,” words that are used fairly regularly but also in contexts that don’t tell the reader much about what they mean.

This also means that the smallest words, like “but” and “as” and “make,” are not looked up either. Most native English speakers know how to navigate the collocative waters of “make” or don’t need to figure out what exactly “as” means in the sentence “You are as dull as a mud turtle.” They recognize that it marks comparison, somehow, and that’s it. But that’s not good enough for lexicography.

It is also a perverse irony that the entries that end up taking the most lexicographical time are usually fairly fixed. Steve Kleinedler, the executive editor of The American Heritage Dictionary, notes that one of his editors overhauled 50 or 60 of the most basic English verbs back in the first decade of the 21st century. “Because he did that, they don’t really need to be done again anytime soon. That was probably the first time they’d been done in 40 years.” This isn’t dereliction on The American Heritage Dictionary’s part: These words don’t make quick semantic shifts. “Adding new idioms to these entries: easy-peasy,” Steve says. “But in terms of overhauling ‘take’ or ‘bring’ or ‘go,’ if you do it once every 50 years, you’re probably set.”

* * *

The citations sorted, I decided to tackle the verb first. The entry for the verb is far longer than the entry for the noun: 107 distinct senses, subsenses, and defined phrases. And, perhaps hidden in all those cards, a few senses or idioms to add.

When one works with paper citations, the unit of work measurement is the pile. Every citation gets sorted into a pile that represents the current definitions for the word, and new piles for potential new definitions. I looked at the galleys, then my desk, and began methodically moving everything on my desk that I could—date stamp, desk calendar, coffee—to the bookshelf behind me.

My first citation read, “She was taken aback.” I exhaled in relief: This is simple. I scanned the galley and found the appropriate definition—“to catch or come upon in a particular situation or action” (sense 3b)—and began my pile. The next handful of citations were similarly dispatched—a pile for sense 2, a pile for sense 1a, a pile for sense 7d—and I began to relax. In spite of its size, this is no different from any other batch, I reasoned. I am going to whip through this, and then I am going to take a two-week vacation, visit my local library, and go outside.

Fate, now duly tempted, intervened. My next cit read, “Reason has taken a back seat to sentiment.” I confidently flipped it onto the pile with “taken aback” and then reconsidered. This use of “take” didn’t really mean “to catch or come upon in a particular situation or action,” did it? I tried substitution: Reason did not catch or come upon a backseat. No: Reason was made secondary to sentiment. I scanned the galleys and saw nothing that matched, then put the citation in a “new sense” pile. But before I could grab the next citation, I thought, “Unless … ”

When a lexicographer says “unless … ” in the middle of defining, you should turn out the lights and go home, first making sure you’ve left them a supply of water and enough nonperishable food to last several days. “Unless … ” almost always marks the beginning of a wild lexical goose chase.

There is a reality to what words mean that is amplified when you’re dealing with the little words. The meaning of a word depends on its context, but if the context changes, so does the meaning of the word. The meaning of “take” in “take a back seat” changes depending on the whole context: “There’s no room up front, so you have to take a back seat” has a different meaning from “reason takes a back seat to sentiment.” This second use is an idiom, which means it gets defined as a phrase at the end of the entry. I started a new pile.

My rhythm had been thrown off, but upon reading the next citation, I was confident I’d regain momentum: “ … take a shit.” Profanity and a clear, fixed idiom that will need its own definition at the end of the entry—yes, I can do this.

Only “take a shit” is not a fixed idiom like “take a back seat” is. You can also take a crap. Or a walk, or a breather, or a nap, or a break. I scanned the galleys, flipping from page to page. “To undertake and make, do, or perform,” sense 17a. I considered. I tried substitution with hysterical results: “to undertake and make a shit,” “to undertake a shit,” “to undertake and do a shit,” “to undertake and perform a shit.” This got me thinking, which is always dangerous. Can one “perform” or “do” a nap? Does one “undertake and make” a breather? Maybe that’s 17b, “to participate in.” But my sprachgefühl, my internal feeling for English and how it worked, screeched: “participate” implies that the thing being participated in has an originating point outside the speaker. So you take (participate in) a meeting, or you take (participate in) a class on French philosophy. I tentatively placed the citation in the pile for 17a, then spent the next five minutes writing each sense number and definition down on a sticky note and affixing it to the top citation of each pile. My note for sense 17a included the parenthetical “(Refine/revise def? Make/do/perform?).”

I sat back and berated myself a bit. I have redefined “Monophysite” and “Nestorianism”; I can swear in a dozen languages; I am not a moron. This should be easy. My next citation read, “ … arrived 20 minutes late, give or take.”

What? This isn’t a verbal use! How did this get in here? I took a pinched-lip look around my cubicle for the guilty party—someone has been in here futzing with my citations!—then realized I was the guilty party. Clearly, I needed to refile this. But where? After five minutes of staring at the citation, I took the well-trod path of least resistance and decided that maybe it’s adverbial (“eh, close enough”). Yes, I’ll just put this citation … in the nonexistent spot for adverbial uses of “take,” because there are no adverbial uses of “take.” My teeth began to hurt.

I placed the citation in a far corner of my desk, which I mentally labeled “Which Will Be Dealt With in Two or Three Days.”

Next: “ … this will only take about a week.” My brain saw “take about” and spat out “phrasal verb.” Phrasal verbs are two- or three-word phrases that are made up of a verb and a preposition or adverb (or both), that function like a verb, and whose meaning cannot be figured out from the meanings of each individual constituent. “Look down on” in “He looked down on lexicography as a career” is a phrasal verb. The whole phrase functions as a verb, and “look down on” here does not mean that the anonymous He was physically towering over lexicography as a career and staring down at it, but rather that he thought lexicography as a career was unimportant or not worth his respect. Phrasal verbs tend to be completely invisible to a native speaker of English, which is why I was so very proud of spotting one at first glance. I created a new pile for the phrasal verb “take about,” and then my sprachgefühl found its voice: “That’s not a phrasal verb.”

I squeezed my eyes shut and silently asked the cosmos to send the office up in a fireball right now. After a moment, I realized that my sprachgefühl had picked loose a bit of information that fell neatly to the bottom of my brainpan: The “about” is entirely optional. Try it: “This will only take a week” and “this will only take about a week” mean almost the same thing. The pivot point for meaning is not “take” but “about,” which means that this use of “take” is a straightforward transitive use. I flipped the card onto the pile for sense 10e(2), “to use up (as space or time).”

It had been an hour, and I had gotten through perhaps 20 citations. I sifted all my “Done” piles into one and grabbed a ruler. The pile of handled citations was a quarter-inch thick. Then I measured the cit boxes. Each was full. Each was 16 inches long.

Over the next two weeks, the tensile strength of my last nerve was tested by “take.” My working definition of “desk” expanded as I ran out of flat spaces to stack citations. Piles appeared on the top of my monitor, in my pencil drawer, filed between rows on my keyboard, teetering on the top of the cubicle wall, shuffled onto the top of the CPU under my desk. Still I didn’t have enough space: I began to carefully, carefully put piles of citations on the floor. My cubicle looked as if it had hosted the world’s neatest ticker-tape parade.

When dealing with entries of this size, you will inevitably hit the Wall. If you run, or have tried to run, then you are familiar with the Wall. It’s the point in a run when you are pushed (or pushing) beyond your physical endurance. Your focus pulls inward on your searing lungs, your aching calves, that hitch in your right hip that is probably because you didn’t stretch but might just be a precursor to your lower body literally (sense 2: figuratively) exploding from the effort you are putting forth. The ground has tilted upward; your feet are made of concrete and are 50 times bigger than you thought; your neck begins to bow because even the effort of holding your fat melon upright is too much. You are not euphoric, or Zen, or any of the other things that Runner’s World magazine makes running look like. You are at the Wall, where you are nothing but a loose collection of human limits.

I hit my human limits about three-quarters of the way through the verb “take.” As I looked at a citation for “took first things first,” I felt myself slowly unspooling into idiocy. I knew the glyphs before me had to be words, because my job was all about words, and I knew they had to be English, because my job was all about English. But knowing something doesn’t make it true. This was all garbage, I thought, and as I felt my brain slip sideways, and the yawing ache open up in my gut, one thought flitted across my mind before I slammed headlong into the lexicographer’s equivalent of the Wall: “Oh my God, I’m going to die at my desk like in that urban legend, and they will find my body under an avalanche of ‘take.’ ”

* * *

That night over dinner, my husband asked if I was OK. I looked up at him, utterly lost. “I don’t think I speak English anymore.” He looked mildly alarmed; he only speaks English. “You’re probably just stressed,” he said. “But what does that even mean?” I whined. “Just thinking about what it means makes my brain itch!” He went back to looking mildly alarmed.

It took me three more days to finish sorting the citations for the verb “take.” I was ecstatic—yes, I had done it!—and then immediately depressed: Shit, I still had to actually do the defining work on “take,” and I still had the noun to go! Lucky for me, I had decided to use the sticky notes to make changes to existing entries. “Make, do, or undertake” didn’t end up getting a revision in the end, but a rough handful of senses needed expanding or fixing; one definition meant to cover uses like “she took the sea air for her health” had been unfortunately phrased “to expose oneself to (as sun or air) for pleasure or physical benefit,” which I hurriedly changed to “to put oneself into (as sun, air, or water) for pleasure or physical benefit” so as not to encourage medicinal flashing.

On the floor were my piles for citations that I needed to mentally squint at a bit more and piles of citations for new senses of “take.” It was late in the afternoon, the sun slicing gold along the wall. Before I took care of those, I decided to reward myself by answering the email correspondence I had let accumulate while I had been ears-deep in “take.” I’d start afresh in the morning.

The next morning, I came into work and discovered that the overnight cleaning crew had decided to move all the piles I had left on the floor, dumping them into a cascade of paper on my chair. It was a cinematic moment: I dropped my bag and stared open-mouthed at the blank spaces where 20 or so piles of citations used to sit. As my sinuses prickled, I realized, almost too late, that I was about to cry, and if I cried, I would most certainly make noise. I left my bag in the middle of the floor and went to the ladies’, where I leaned against the paper towel dispenser and wondered if it was too late to go back to the bakery where I had once worked and have indignant people throw cakes at my head again.

Lexicography is a steady plod in one direction: onward. I was doing no good standing there with my head on the cool plastic. Besides, a few of my colleagues were waiting for me to move so they could dry their hands. I re-sorted the tidy stack the cleaning crew left and papered every flat surface within five feet of my cubicle with “DO NOT MOVE MY PAPERS!!! KLS!!!!” I sat grimly in my chair and decided that a little fun was in order: It was time to stamp the covered citations and file them away.

When you’re done working on an entry, the paper citations get put in one of three places: the “Used” group, which are the citations used as evidence for every existing definition in the entry; the “New” group, which holds the citations for each new sense you draft; and the “Rejected” group, which holds the citations for any use whose meaning isn’t covered by the existing entry or by a newly proposed definition. Used and new citations are stamped by the editor who worked on the entry to mark that they were used for a particular book. When the whole floor was consumed with a defining project, you’d occasionally hear a sudden rhythmic thumping, like someone tapping their toe in miniature. It was an editor stamping citations.

I took out my customized date stamp and began marking the covered cits, pile by pile, as used. After the first handful, I stamped a little more exuberantly, and my cubemate hemmed in irritation. No matter. I had no punching bag to pummel; I had no nuclear device to detonate. But I had a date stamp, and by the power vested in me by Samuel Johnson and Noah Webster, I was going to put this goddamned verb to bed.