“Why should anyone be interested in my boring, alienated, marginal, messy life?” the British writer Angela Carter replied when approached with the prospect of a biography while she was still in her 40s. Just a few years later, she was so famous the question seemed ridiculous—but then she’d just died, of lung cancer at the age of 51. Her untimely death in 1992, as Edmund Gordon, author of The Invention of Angela Carter, puts it, made her a “household name” in England. “Rhapsodic” obituaries filled the newspapers and in the course of a year the British Academy received 40 proposals for doctoral research on her work. Her books all sold out. The closest American parallel is the posthumous canonization of David Foster Wallace, a writer who, like Carter, was often viewed as puzzlingly obscurantist and show-offy during his lifetime, but in death suddenly achieved sainthood in the eyes of young literary aspirants.

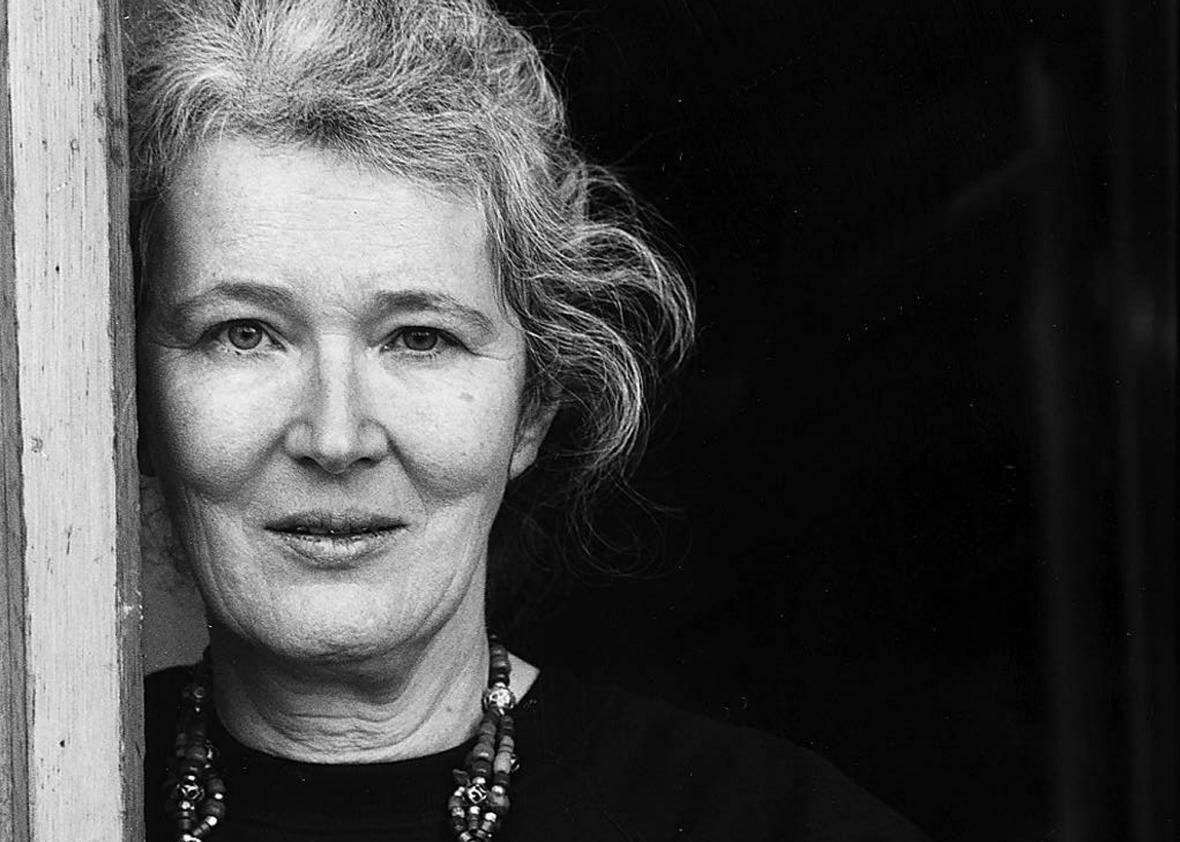

Although in Carter’s case she was viewed more as a fairy godmother than anything so Judeo-Christian as a saint. She cultivated witchy associations by embracing the premature graying of her long, flowing hair and filling the house she shared with her second husband (a carpenter and potter 15 years her junior) with peculiar Victorian bric-a-brac. Perhaps more than any other 20th-century author she championed the incorporation of fairy tales and folklore into modern fiction, although she was also fascinated by Gothics, James Joyce, the Marquis de Sade, and science fiction. (One of her novels is the post-apocalyptic tale of a man subjected to a forcible sex change operation by a gang of radical feminists in the California desert.) Despite the “wise woman” label plastered onto her after her death, she was anything but New Age–y, a stout atheist who considered “mother goddesses” to be “just as silly a notion as father gods.”

Excess is the abiding principle of her fiction, excess and freedom, both inclinations that put her at odds with the prevailing literary mode of her day, which was dominated by what Gordon describes as “sober social realists” like Angus Wilson and Kingsley Amis. Although Carter is much less well-known in America than in her native land, her influence is everywhere, most obviously in novels like Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! and the short stories of Kelly Link, but detectable wherever writers promiscuously blend genres, where primeval myth rubs shoulders with smartphones, as in the work of Neil Gaiman and Jeff VanderMeer. Carter had the misfortune to be slightly ahead of her time; she played mentor to such budding talents as Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan, and Kazuo Ishiguro, novelists who stepped through the cracks she opened up in the genteel carapace of British fiction. They revered her; Rushdie, when still an unknown, publicly scolded a visiting dignitary for patronizing her at a London party, explaining, “This was like the greatest writer in England.” When Rushdie’s generation of British novelists—which also included Martin Amis and Julian Barnes—rocketed to international fame, Carter was happy for them (especially for Rushdie, whom she considered both a personal and an aesthetic ally), but the imbalance between the recognition these male writers received and the prestige accorded to her own work was not lost on her. “She knew that she was Angela Carter,” Rushdie told Gordon, “but she wouldn’t have minded a few other people knowing.”

Carter’s life, as Gordon tells it, was as messy as she claimed, but it was anything but boring. It began in an atmosphere of stifling lower-middle-class London respectability and broke out into the counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s. She married young—mostly to escape an exceptionally protective and intrusive mother—to a depressive folk rock aficionado, worked as a journalist, and wrote a few sharp-edged and rather unpleasant novels set in the hippie enclaves of provincial England. With prize money she received for one of these books, she left her marriage in 1969 to live for two years in Japan, where she had a ferocious affair with a local slacker—a man Gordon succeeded in tracking down and visiting decades later in Tokyo, offering up the choice detail that his bathroom was wallpapered in photos of Elvis Presley. It was in Asia that Carter first read Jorge Luis Borges, “the grand old man to whom I owe so much.” The jewel box stories she began to write under the dual influence of Japan and the Argentinian master marked the emergence of her mature vision: often surreal, always exquisite, iconoclastic and soaked in a heady sensuality.

The novels from this period, The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman and The Passion of New Eve, were written in the 18th-century mode. Their heroes wander from adventure to adventure encountering people who espouse bizarre and politically pointed philosophies. In the first, the eponymous doctor invents a device that turns dreams and unconscious wishes into reality and threatens the powers that be in an unnamed South American nation. The novel’s narrator is charged by the “Minister of Determination” with assassinating him, “as inconspicuously as possible.” The assassin pursues the doctor across a chaotic dreamscape, falling in love with his daughter, Albertina, who at first appears to be a beautiful young man. The Passion of New Eve is the book with the forced sex change, and it also features a legendarily beautiful film star, modeled after Marlene Dietrich, who turns out to be a man.

In 1979, Carter published an influential book-length essay, The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography, the opening sentence of which constituted a shot over the bow of the emerging anti-porn faction of feminism: “We do not go to bed in simple pairs: even if we choose not to refer to them, we still drag there with us the cultural impedimenta of our social class, our parents’ lives, our bank balances, our sexual and emotional expectations, our unique biographies—all the bits and pieces of our unique existences.” Pornography, Carter wrote, usually strips all of these impedimenta from the depiction of sex, transforming the participants into archetypes of the male and female frolicking in “an artificial paradise of gratified sexuality,” while anti-porn theory reduces them to victim and victimizer. What Carter found intriguing in Sade is his acknowledgement of the political underpinnings inherent in all sexual encounters. A “moral pornographer,” in her view, can use the form “as a critique of current relations between the sexes”—or, for that matter, among races and classes. Like most of Carter’s work, The Sadeian Woman is anti-essentialist. She didn’t believe that women were naturally gentle, cooperative, or maternal, as was often claimed by feminists of her time.

Although Carter sometimes described herself as a radical feminist, The Sadeian Woman earned her the wrath of intellectual figures associated with that label. Andrea Dworkin denounced the essay as “pseudofeminist,” and activists slapped the paperback edition with a sticker declaring the cover (featuring a painting by the surrealist Clovis Trouille) offensive to women. Carter’s response was that if she could get up “the Dworkin proboscis, then my living has not been in vain.” This contretemps illustrates an aspect of Carter’s life and work that Gordon neglects to fully explore. She was, as he persuasively argues, engaged in a lifelong project of creating and recreating for herself identities that fit better and more comfortably than the identities handed to her by tradition, stereotype, and power. But it is also true that Carter’s chosen beliefs, sentiments, and alliances were often at odds with each other, making it difficult to form a stable image of her. “Angela Carter” is a flickering entity, part fishwife and part fairy.

In person, for example, she was both shy and brazen, quiet for long periods and then prone to extravagant provocations. Gordon quotes a friend who professed himself baffled by critics who sometimes accused her of toeing the party line on women’s issues. “If there was a kind of consensus in the room about anything,” he said, “she’d immediately bowl a googly in order just to see what happened.” In her review of Gordon’s biography for the London Review of Books, the critic Jenny Turner passes on an anecdote from the American novelist Rick Moody, another of Carter’s protégés, who recalled an incident in a creative writing workshop Carter led at Brown University. “Some young guy in the back … raised his hand and, with a sort of withering skepticism, asked, ‘Well, what’s your work like?’ ” Carter, who had a soft and frequently hesitant speaking voice, issued several ums and ahs, and then replied, “My work cuts like a steel blade at the base of a man’s penis.”

Carter’s sense of herself as a political artist was challenged by the manifest sway exerted by Freud (and such Freud followers as Bruno Bettelheim) on her fiction, although she was also always rebelling against those authorities. Her stories and novels often seem to be less about conflicts in the world than those within the psyche. The quest to assassinate Doctor Hoffman has more resonance as metaphor for the struggle between the conscious and the unconscious minds than as a depiction of any actual battle for earthly power. If her fiction had been as political as she sometimes believed it to be, or if it had merely been a display of her gorgeously epicurean prose—either way—it would have been dull. But swinging like a trapeze artist from one imperative to the next, she was magnificent.

In Carter’s masterpiece, The Bloody Chamber, a collection of short stories based on classic fairy tales, this tension suffuses the book with a thrilling intensity. She conveys both the gravitational allure of archetypes and the utopian defiance that seeks to smash them to bits. The title story, based on “Bluebeard,” is narrated by a young woman both enthralled and repelled by her rich, commanding, older bridegroom, with his “white, heavy flesh” and his perception in her of “a potentiality for corruption that took my breath away.” Surrendering to him is voluptuous and terrifying at the same time, and only heroism from a highly unexpected quarter succeeds in rescuing her from his clutches. Carter’s multiple variations on “Little Red Riding Hood” inspired Neil Jordan’s ravishing 1984 film The Company of Wolves (co-written with Carter); the most memorable ends with Red Riding Hood lustily ripping the wolf’s shirt off and laughing in his face when he threatens to eat her: “She knew she was nobody’s meat.”

Carter’s final two novels, Nights at the Circus and Wise Children, took a carnivalesque turn. Both center on female performers—an aerialist of mysterious origin whose apparently fake costume wings are real and functional, and twin chorus girls frolicking through what Gordon characterizes as “a splendidly busy, absurdly over-the-top burlesque of Shakespearian motifs.” Carter adored flashy, lowbrow, bawdy entertainments, especially those founded on a shamelessly artificial beauty. “Show business, being a showgirl,” she told one interviewer, expressing an idea now common but then quite rare among feminists, “is a very simple metaphor simply for being a woman, for being aware of your femininity, being aware of yourself as a woman and having to use it to negotiate with the world.” Understand this as a performance rather than as an immutable definition of your being and you can revel in it as well as turn it to your advantage. In the final chapter of Wise Children, the now-elderly twins saucily paint up their faces in preparation for a big party, figuring, “We could still show them a thing or two, even if they couldn’t stand the sight.”

If only Carter herself could have reached such a vintage—some women just seem born to become fabulous old ladies. She might have finally gotten around to the novels and screenplays she planned to write about Lizzie Borden and two New Zealand girls, Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme, convicted of killing Parker’s mother. What she did finish shortly before her death was compiling The Virago Book of Fairy Tales, a global collection of folk tales featuring female protagonists, for the publishing company founded by her close friend, Carmen Callil, to publish female writers. Gordon quotes a footnote from this volume that seems to capture Carter’s spirit better than any manifesto. “Swahili storytellers,” she explains, “believe that women are incorrigibly wicked, diabolically cunning, and sexually insatiable. I hope this is true, for the sake of the women.”

—

The Invention of Angela Carter by Edmund Gordon. Oxford University Press.