In 1996, the ghostwriter Barbara Feinman endured the worst year of her professional life. Her job—as the title of her memoir, Pretend I’m Not Here, indicates—was to fade into the background. Instead, she had tabloid TV crews camped on her lawn, was portrayed as a wronged underling in the national press, and was called to testify before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. She’d been caught up in the never-ending whirlwind of the Clinton scandal complex, and she had no idea why.

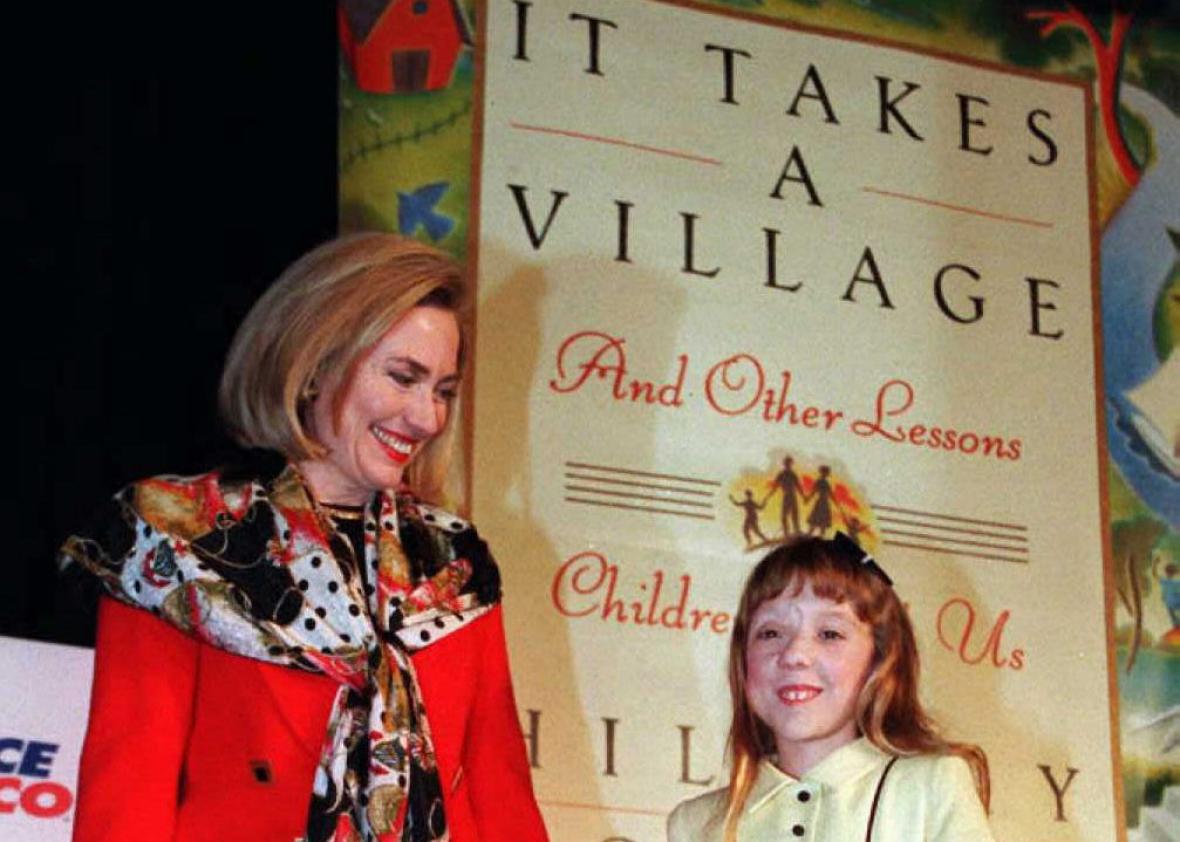

Depending on who you asked back in 1996, Feinman had either provided modest research assistance on first lady Hillary Clinton’s It Takes a Village or had written most of Clinton’s book herself and then been stiffed on due credit for her work. In particular, the furor centered on why Feinman had not been mentioned in the book’s acknowledgements, the standard method of recognizing a ghostwriter’s contribution. Feinman (who has published this memoir under her married name, Barbara Feinman Todd) felt so rattled by White House imputations of her inadequacy that she couldn’t bear to read the published version of the book for 20 years. When she finally did, as research for Pretend I’m Not Here, she found that “at least 75 percent of the draft that I produced with Mrs. Clinton was used in the published version—some parts intact, other parts edited or moved around.” To “dismiss” her role in writing It Takes a Village was, she concludes, “dishonest.”

By the time you get to that conclusion, on page 209 of this very likable book, Feinman is just about the only figure in Pretend I’m Not Here who seems trustworthy. She portrays herself, in her ghostwriting heyday, as a conscientious if overly eager-to-please naif navigating her way through a Beltway landscape populated by charismatic but flawed titans. (She has since become an English professor at Georgetown University and the founder of the university’s journalism program.) Among the books she helped to research and write in the 1980s and ’90s are Bob Woodward’s Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA, Carl Bernstein’s Loyalties, former Washington Post executive editor Benjamin Bradlee’s A Good Life, and former Nebraska Sen. Bob Kerrey’s war memoir When I Was a Young Man.

The ghostwriter labors, discreetly, at the center of a web of contradictory American beliefs and desires. Above all, she is the servant of fame, because publishers bring in a ghost when the ostensible author has a name celebrated enough to sell books but a career too demanding to permit writing one. Almost every autobiography published by a politician or a celebrity is actually written by a ghost. (The exceptions, like Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father, are regarded as objects of wonder in the industry.) Occasionally a dispute over the ghost’s work highlights the absurdity of this practice, as when the basketball star Charles Barkley attempted, in 1991, to halt the publication of his own autobiography because he claimed it misquoted him; he not only hadn’t written it, but he hadn’t even read it before it went to press. Ghostwriters crank out novels for reality TV and YouTube stars and whip celebrity-chef cookbooks into publishable shape. Most of these projects are naked attempts to capitalize on celebrity, but political books can have murkier directives. “People in Washington,” Feinman writes, “rarely write books because the writing muse visits them; rather, they have a campaign to win, a cause to lobby for, a scandal to overcome, or an image to fix.”

It Takes a Village was meant to remind the public of Hillary Clinton’s work on behalf of women and children in the aftermath of her disastrous attempt to overhaul the nation’s health care system. For Feinman—who came up with the title, based on an African proverb—the book was the culmination of over a decade of playing literary handmaiden to Washington luminaries, people who, in their initial meetings, often inspired her with so much awe she could barely speak. On her first day sorting through Bradlee’s files in his Georgetown mansion, she was so intimidated by his wife, society journalist Sally Quinn, that she refused Quinn’s offer of lunch despite being famished. The two women later became friendly, but when Quinn spoke up on Feinman’s behalf during the It Takes a Village fracas, she portrayed Feinman (condescendingly and incorrectly) as desperate for both cash and recognition. “She would have died and gone to heaven,” Quinn told the New Yorker, simply to have been thanked in the book’s acknowledgements.

Understandably, seeing herself described in this way made Feinman cringe, and yet she was thrilled to work with such distinguished and powerful clients, to be invited to spend the night in the White House, and to dine with the president. Yet she was ambivalent about the career she had fallen into when, as a copy aide at the Post, she applied for a job as Woodward’s researcher. A former English major, she dreamed of becoming a novelist, not a journalist, but her nascent run at the form—the sort of book that might have been sold as chick lit but back then prompted her agent to dub her the “Jewish Amy Tan”—never got off the ground. Ghostwriting certainly pays better than writing novels, but for Feinman, it wasn’t always worth it. “The act of writing in the voice of others,” she explains, “in addition to being taken away from my own writing, meant that I was being taken away from myself.” By marinating in the lives, outlooks, language, and even mannerisms of her subjects, she found that “their problems became more important than mine, their dreams more alluring. Their mental stuff took up all the room in my head and my heart, pushing mine to the periphery.”

The big reveal in Pretend I’m Not Here is Feinman’s theory about why Hillary Clinton—who had previously treated her cordially, with never “a single cross word spoken between us”—suddenly turned on her, removing her from the acknowledgements of It Takes a Village and even, at one point, instructing her publisher to withhold the final installment of her fee for the job. Although Feinman has never published a novel of her own, she has certainly learned how to apply a novelist’s storytelling skills to real life in eking out the root of this mystery. Early on, she describes a walk she took with Woodward, her onetime employer and mentor, shortly after she finished work on It Takes a Village. Woodward, she soon realized, was treating her not like a friend or a protégée but like a source, and against her better judgment she shared with him a story that she felt reflected the embattled mood at the Clinton White House. Hillary Clinton had invited Feinman (for reasons that remain unclear) to a meeting with a New Age author, Jean Houston, during which Houston encouraged Clinton to engage in imaginary spiritual communion with Eleanor Roosevelt and Mahatma Gandhi.

HarpersCollins

Although Woodward promised Feinman he would not pursue this story in the book he was writing on the 1996 presidential campaign, he nevertheless sought to confirm it with other participants in the meeting. This, of course, made it clear to Clinton and her staff that Feinman had broken the confidentiality agreement that was part of her contract. Although she castigates herself for her own foolishness in confiding in Woodward, Feinman has never quite gotten over what she describes as his “breathtaking betrayal.” (It’s also worth noting that if Clinton and her staff had leveled with Feinman about her transgression instead of practicing the wagon-circling and communication shutdown for which she would become notorious, everyone might have been saved a lot of trouble.)

For Feinman, Woodward’s expedient duplicity came to epitomize a Washington culture she had grown to detest, with its ruthless scrabbling for inside information and access to power. “He sounded slightly sheepish,” she writes of the phone call in which Woodward confessed, “but at the same time he didn’t seem to regret what he had done. He seemed focused on the big splash he was about to make. A splash in the same pool in which I was drowning.” As piranha-infested as that pool once appeared to Feinman, it looks, from the nostalgic perspective of 2017, to be positively genteel. Reflecting on the stalled political career of Bob Kerrey, who became a genuine friend (when she was holed up in a Wyoming hotel room during the final stretch of writing It Takes a Village, he sent Feinman a care package containing, among other things, one of his famous handmade collages), she concludes that his “proclivity for being who he really was” kept him from making a credible run at the White House. “To become commander in chief, there could be no unscripted or unedited moment,” she writes, in one of the passages that makes Pretend I’m Not Here read like a dispatch from a bygone age.

Feinman can blame her own travails on a combination of old-Washington culture and the peculiar self-abnegation demanded of ghostwriters, but the truth is that similarly nasty dramas transpire in New York and Hollywood every week. In the eyes of Clinton and Woodward, they were important, and Feinman was not. They were the leading players, and she had, at best, a supporting role. But more to the point, at least some part of Feinman agreed with them. As a ghostwriter, her relationship to fame and power became a more consuming version of many Americans’ fixation on celebrities, people whose lives can seem so much grander, so much more real, than our own. It’s a fixation that has culminated in an electorate so dazzled by the theatrics of a reality TV star that it has placed him, despite his evident lack of both expertise and basic human empathy, in the highest office in the land. If Feinman lost herself for a while in the larger-than-life escapades of people who treated her as little more than a means to an end, if she became a ghost in more ways than one, then today she must feel that she has plenty of company.

—

Pretend I’m Not Here: How I Worked With Three Newspaper Icons, One Powerful First Lady, and Still Managed to Dig Myself Out of the Washington Swamp by Barbara Feinman Todd. William Morrow.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.