Each year in Norway, thousands of pilgrims visit a statue of a 14th-century woman outside a church in the rural valley she called home. The woman is not a saint or a pioneer, but an ordinary mother—a fictional one, at that. She is Kristin Lavransdatter, the bewitching heroine of a literary trilogy written in Norwegian in the early 1920s. The series’ author, Sigrid Undset, received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1928 for “her powerful descriptions of Northern life during the Middle Ages.” The self-taught writer and her heroine are still revered in Norway; Undset’s home is a museum, and “Kristin’s” farm is a tourist attraction. But outside Scandinavia, Undset’s masterpiece was nearly forgotten by the end of the previous century. An American academic journal described the author’s reputation back then flatly: “To literate lay readers she is no longer a major author.”

In recent years, however, there have been signs that Kristin Lavransdatter is beginning to build up an international following to rival her domestic one. Her rescue from literary obscurity started in 1997, with the release of the first volume of Tiina Nunnally’s new translation into English from the Norwegian. Nunnally’s elegant interpretation strips the text of the leaden medieval-isms (“methought,” “belike”) favored by the previous English version. These days, Undset encomia are a staple on Catholic-interest websites, and certain corners of literary Twitter flog the series relentlessly. In 2015, William T. Vollmann told the New York Times that Kristin was his favorite fictional character, noting correctly that the trilogy “bears many rereadings.”

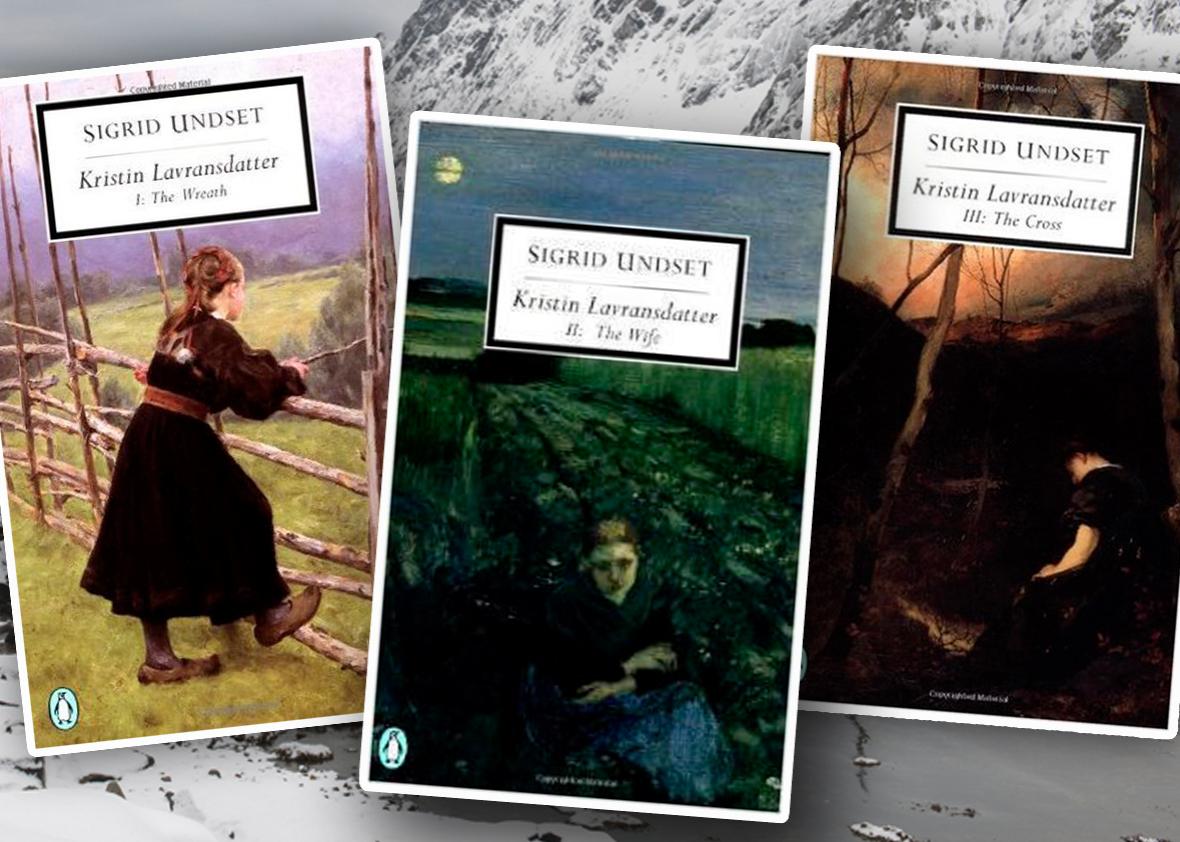

Kristin Lavransdatter’s three volumes total more than 1,000 pages, which follow the daughter of a wealthy farmer from age 7 through her dramatic death. (I won’t spoil major plot twists here, but if you’re worried, stop reading this and just go buy the books already.) In The Wreath, Kristin meets the great love of her life, who is not the man her parents chose for her. (The also-ran isn’t an awful guy; she could tolerate him “especially when he was talking to the others and did not touch her or speak to her.”) In the second book, The Wife, she gives birth to many sons and deals with the fallout of her husband’s rash meddling in royal politics. And in the final volume, The Cross, Kristin watches her sons grow up and, oh, by the way, reckons with the future of her immortal soul.

Undset was an obsessive researcher, and her 14th-century Norway has texture down to the dirt of the smithy floor. She captures annual agricultural rhythms of shortage and plenty, obscure ecclesiastical laws governing punishments for adultery, and the way the men douse themselves in ice water to sober up for church after Christmas festivities. Her descriptions of food, decor, and clothing are precise: the way Kristin strews juniper and flowers on the floor to prepare for guests, and her blue-violet leather shoes “stitched with silver and rose-color stones.”

If HBO is looking for its next miniseries, it should give Kristin Lavransdatter the proper adaptation it deserves. (A Scandinavian film version directed by Liv Ullmann in 1995 was plagued with production problems and received middling reviews.) Rereading the trilogy this fall, I kept thinking of Olive Kitteridge, another powerful novel about a prickly mother turned into a worthy HBO miniseries. This trilogy includes illicit sex, affairs, a church fire, an attempted rape, ocean voyages, rebellious virgins cooped up in a convent, predatory priests, an attempted human sacrifice, floods, fights, murders, violent suicide, a gay king, drunken revelry, the Bubonic Plague, deathbed confessions, and sex that makes its heroine ache “with astonishment—that this was the iniquity that all the songs were about.” And yet all the outward drama is deployed in service of a story about an ordinary woman’s quietly shifting interior life. Another tempting comparison is Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, whose huge commercial success suggests there is a market for series in translation about fierce, complicated women navigating their culturally conservative European milieu.

To sell the Kristin Lavransdatter novels as “hot” in terms of either content or buzziness somewhat misses the point, though. “Listing the strengths of Kristin Lavransdatter will not make the novel fashionable,” the scholar Otto Reinert wrote in 1999. “It is unexciting labor to claim merit for the conventional.” He was referring to both the books’ style and their moral tenor. It would be criminally simplistic to describe the series as “conservative,” but there’s a reason it appeals so powerfully to a certain kind of bookish Christian reader. As flawed as Kristin is—she is proud, lustful, brooding, and fails to live up to her own moral standards—she is a devout believer, and the books are intimately concerned with her relationship with God. Undset was a Catholic convert, and one of the most remarkable things about the trilogy is that it’s a rare literary depiction of religious people that is both empathetic and unsentimental.

Early in the first book, Kristin’s angelic younger sister is gravely injured in a freak accident caused by a large ox. When the family realizes that the injury is permanent, they propose that Kristin enter a convent, as a kind of holy bargaining chip. She balks at this plan:

She resisted the idea that God would perform a miracle for Ulvhild if she became a nun. … She had the feeling that it was as Brother Edvin had said—that if someone had enough faith, then he could indeed work miracles. But she did not want that kind of faith; she did not love God and His Mother and the saints in that way. She would never love them in that way. She loved the world and longed for the world.

That internal battle between piety and hunger, between heaven and earth, echoes throughout the next 1,000 pages. Reading Kristin Lavransdatter made me realize how rarely I’ve encountered a serious 20th- or 21st-century novel that recognizes that “following your heart” might not be the key to happiness or goodness. The annals of historical fiction are filled with headstrong heroines who struggle between their own desires and the strictures of their fuddy-duddy communities, of course. But the revelatory thing about Undset’s approach is that it does not presume the community is wrong.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.