Octavia Butler’s Kindred, a slave narrative–meets–sci-fi–time-travel tale, was first published in 1979. Set in 1976, it centers on a black woman named Dana who is unpacking at her new home in California when she is suddenly transported to early-1800s Maryland, where slavery is legal. She time-travels a total of six times over the course of this story, spending more and more time in the past—months even—while only hours tick by in her present. Dana’s time-traveling is connected to Rufus Weylin, a distant ancestor of hers who was the son of a plantation owner and bore children with a slave.* Every time Dana is called back to the past, it’s because Rufus needs her, whether because of a near-drowning at the age of 5 or a fight in his 20s. Dana uses her time in the past to help change Rufus’ life for the better, but as he grows older, he seems to push back more and more against her influence. Now adapter Damian Duffy and artist John Jennings have produced a graphic novel adaptation of Butler’s work, which casts her words in a new light.

Science-fiction author Nnedi Okorafor wrote an introduction for the adaptation, in which she mentions emailing Butler after 9/11. She quotes an email from Butler, giving her thoughts on the perpetrators of the attack and linking them back to the theme of Kindred:

One of my favourite quotes—so sadly true—is from Steve Biko:

“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressed is the mind of the oppressed.”

There is also the sad reality that it takes very little to set off young men who want to feel powerful and important, but who are either unwilling or unable to find constructive outlets for their energies. Testosterone poisoning. And men have the nerve to complain about women’s hormonal mood swings.

Amazon

“Testosterone poisoning” is an apt description for what happens to Rufus, and this concept is portrayed vividly in the comic. The idea is foreshadowed in a section titled “The Fire,” with a close-up panel of Rufus’ face as a young boy. His expression is seething anger; in the panel before it, Dana laughed at the idea of calling him “master.” “You’ll get into trouble if you don’t,” he replies, “if daddy hears you.” This could be read as a charitable, well-intentioned survival tip if it weren’t for his expression—the dark shadows, the furrowed brow, the straight mouth.

At every turn, Rufus refuses constructive outlets for his anger—such as, say, talking through his feelings with others—which leaves us with an angry young white man who self-destructs and takes those who have no control over their own lives with him. Even his idea of love is warped by his need to feel powerful at the expense of the other slaves and also Dana. Rufus’ self-poisoning is infuriating to us as readers; we see him slap away change in pursuit of hollow power that ultimately leaves him all alone.

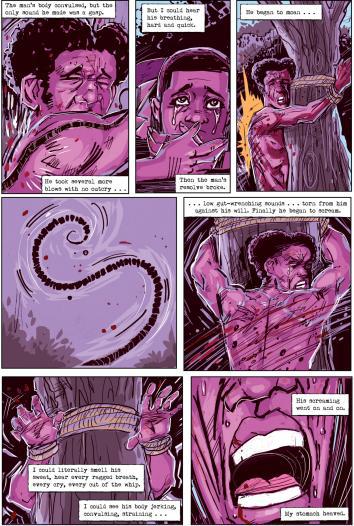

Butler’s original novel is a powerful commentary on how the past informs the present and how we engage with both. But this adaptation makes an even more vivid statement about black Americans’ relationship with history. The kinetic lines feel urgent, messy, and visceral. The colors for scenes set in the present are muted while the colors of the past are vibrant, almost like a bright wake-up call to reality. When Dana time-travels for the second time, she witnesses a slave lashing. She explains how she’s seen such scenes in films and television before, but this experience, needless to say, was different. She could smell the sweat and blood. We’re given different perspectives on the event, as the panels show a close-up of the slave with spattered blood across his back and then the recoiled whip taking some of the blood with it. Yellow is used in one panel to indicate the loud, painful motion of the whip across human flesh. There are two side-by-side panels near the end of the ordeal: one of the slave crying and the other a frame of Dana’s face crying as reckons with what she’s seen. It made me think of the complacency the present affords us with regard to the past. Of course, black people now still have plenty of violence to contend with, but slavery, for those of us who haven’t lived it, is still a textbook experience. For Dana, it was a textbook experience until she was literally thrown backward in time.

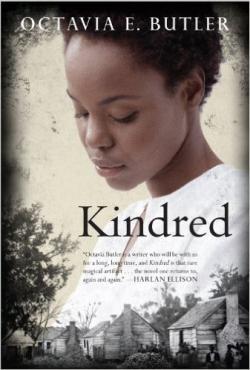

Abrams Books

It’s tempting to think about Dana and Rufus’ relationship as a mirror to our current political moment—in particular, the danger of the widespread calls postelection for the left to sympathize with bigots. It’s an active strain in American culture today: the idea that marginalized people should be willing to provide patient education to white people who don’t see them as equals. This amounts to asking the traumatized and oppressed to fight within the confines of what oppressors deem respectable. And it’s akin to asking Dana to go back in time and save a man who repeatedly rejects her humanity, when her own survival and mental health are at stake.

It wasn’t until the end of the comic that I fully understood Jennings’ art. In the beginning, the line work seemed hurried and rough, but as the details accumulated, his style began to read more as intensity than carelessness. Jennings has a knack for conveying profound and difficult human emotions through facial expressions: rage, despair, fear.

There are two panels next to each other on one of the final pages. Each is a close-up: half of Dana’s face and half of Rufus’. The gutter of white space between the panels ensures that they remain separate, but you can see easily the visual connection between the two. Both faces are furious, their brows drawn downward. The one difference is a tear streaming down Dana’s face. The gutter represents the time that divides them and will always divide them. Given the book’s ending, it’s hard to say whether Butler herself was hopeful about the future. But she did care about confronting the darkest parts of humanity—our biases, privileges, history, and ugliest truths.

—

Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation. Octavia Butler, Damian Duffy, and John Jennings. Abrams ComicArts.

Read all the articles in the Slate Book Review.

*Correction, Jan. 23, 2017: This piece originally misstated that the character Rufus Weylin is the son of a slave. He bore children with a slave. (Return.)