In 2012, a month after the publication of her memoir, Wild, Cheryl Strayed was on a book tour, soaking up the wonder of her first big success as an author, when her husband texted her to say that their rent check had bounced. “We couldn’t complain to anyone,” Strayed told Manjula Martin, editor of the new anthology Scratch: Writers, Money, and the Art of Making a Living: “My book is on the New York Times best-seller list right now and we do not have any money in our checking account.”

Few connections are more mysterious than the one between writing books and making money. Strayed most definitely did make money on Wild, which was adapted into an Oscar-nominated film with Reese Witherspoon, but she didn’t get her first royalty check for it until 2013, “so it was almost a year before my life actually changed.” Yes, there was that $400,000 advance—an amount to make any aspiring memoirist’s eyes go dreamily unfocused—but Strayed and her husband had run up so much credit card debt that almost all of the money went to paying it off and supporting her family while she finished writing the book. Book advances, which are advances against the royalties that will be earned after the book is published, aren’t forked out in one lump sum, either. The payments come parceled out in (typically) three or four checks paid on signing the contract, on delivery of the manuscript, and on publication. The writer’s literary agent then takes a percentage of that. When Strayed sold her first novel a few years earlier for the seemingly handsome sum of $100,000, the advance amounted to, as she puts it, “about $21,000 a year over the course of four years, and I paid a third of that to the IRS … it was like getting a grant every year for four years. But it wasn’t enough to live off.”

It’s worth leading with all these numbers because, as Scratch repeatedly demonstrates, the nitty-gritty on this stuff is in short supply in the wider writerly imagination, while fantasy, evasion, and envious brooding runneth over. Strayed is among the few prospering contributors to this collection of essays and interviews who speaks so explicitly. (“We’re only hurting ourselves as writers by being so secretive about money,” she told Martin.) Another is Roxane Gay—author, columnist, editor, publisher, professor, public speaker—who reports that she made approximately $150,000 in 2014. That’s a good income by almost any standard, but does it match your sense of Gay’s prominence and productivity? (Surely there are plenty of professors who make that much, or more, from their academic work alone.) Depending on your media diet, Gay may or may not constitute a “famous writer” in your eyes, and depending on how much you think famous writers must earn, her income may strike you as surprisingly modest. Or perhaps this entire topic offends you. There are still a few idealists out there cherishing the belief that writing, as art, mustn’t be contaminated by filthy lucre.

Amazon

Like most anthologies, Scratch is uneven; not every contributor is equally talented and none is able to drill very deeply into the relationship between work and money in writers’ lives. The book originated with a (now defunct) online magazine of the same title, developed—as Martin, who edited both, explains—“out of a need for greater transparency in the discussion about work and money within the community of writers.” But if the mission statement of this anthology is to demystify “how, exactly, literature and the people who make it are valued,” many of the pieces here seem to deflect away from transparency as if repelled by a magnetic field. If their authors set out to write about money, they end up spinning their wheels on the more formulaic and far less interesting subjects of self-discovery, dream-following, and “career”—a label given, often by wooly-headed Brooklynites, to an amorphous blend of personal reputation and public persona. Writers know so little about how other writers make ends meet that it’s difficult for them to have much perspective on their own ability to do so. But even when you find out that Strayed nearly sunk under her debts while Yiyun Li enjoyed a relatively stress-free transition from pre-med to fiction writing—three years after making the jump, she’d published in both the Paris Review and the New Yorker—the sum of both their stories still doesn’t offer a stable picture of how most writers make a living.

Many don’t, or at least not from writing alone. If they are novelists (or—God forbid!—poets), they almost always rely on teaching for steady income. What they teach, for the most part, is writing; that is, as none of the contributors has quite the nerve to state baldly, in order to support themselves, they train others to do the work that isn’t providing them with a viable living. At times, the entire fiction-writing profession resembles a pyramid scheme swathed in a dewy mist of romantic yearning. Many of these essays begin with wry descriptions of the author’s youthful madness in moving to New York or throwing away a dependable day job or career path to “be a writer,” a phrase that often connotes earning enough money to live by writing alone. Yet this is never a simple transaction. For authors, money, however obscurely, is always entangled with legitimacy because writers have for centuries equated publication with professional and artistic anointment. Anyone can call themselves “a writer,” but to be published (by somebody other than yourself) is to be a real writer.

It’s indeed a significant testimonial when someone else wants to invest their own money in a writer’s work, so it’s easy to forget that a publisher is actually the writer’s business partner, not a conferrer of literary worth. In their candid moments, most publishers will admit going into business with writers whose work they regard as subliterary because they believe that they can profit from their books. This is still considered shocking in some unsophisticated quarters, but publishing isn’t literature: Literature is literature. Publishing is a separate, if related enterprise. The danger of confusing the two is nowhere more apparent in this anthology than in Kiese Laymon’s wrenching “You Are the Second Person” (originally published in Guernica magazine) describing a tortuous four-year relationship with a manipulative, capricious, dishonest editor. Laymon’s vulnerability to “Brandon Farley” (an invented name) is multiplied by Laymon’s isolation and by race; both men are black, and Farley harangues the author into endless, commercializing revisions of his young adult novel by claiming they’re necessary to make him a “real black writer.”

Farley’s financial power was real; his ability to bestow “real black writer” status was entirely imaginary. But the former, in Laymon’s eyes, endorsed the latter, costing the author much agony. The least-fraught voices in Scratch are those of journalists (Susan Orlean), publishing professionals who also write fiction (Kate McKean), and a ghost writer, Sari Botton, whose war stories offer a rare glimpse into one of book publishing’s most overlooked trades. “I have made as much as $3 a word and as little as nothing,” writes Alexander Chee, a novelist and teacher who also regularly writes nonfiction for newspapers and magazines, marveling over “the asymmetry between effort and reward” in journalism. Ironically, it’s those writers most practiced at selling their words for money who are the least prone to conflating literary merit with cash, and the least likely to agonize over their own authenticity. “Being a writer is running a small business,” Orlean observes matter-of-factly, in flat contradiction to the starry-eyed visions of “the writer’s life” that other contributors recall harboring. In a survey of the early history of writing as a commodity, Colin Dickey cautions that once a text’s “value is determined by the marketplace rather than the writer or the reader, our relationship to literature becomes estranged.” But it isn’t a book’s value that the marketplace sets, only its price. It is time spent in the market that teaches you how to tell the difference.

That books still make money at all is something of a miracle. (And to be fair, the vast majority of books don’t make money; publishing, like baseball, is a game predicated on failure.) No market could be less rationalized, or as Strayed puts it, “There’s no other job in the world where you get your master’s degree in that field and you’re like, ‘Well, I might make zero or I might make $5 million.’ ” She swears she would have written her books anyway, “whether I was paid for them or not,” and I don’t doubt she’s telling the truth about that. But would she still be able to produce the same big-hearted books if she were delivering them into a world that refused to reward her for them? Getting paid more than zero for your work is the first step toward learning what it’s really worth to you, the best way to learn to stop obsessing about what it’s worth to everybody else.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

–

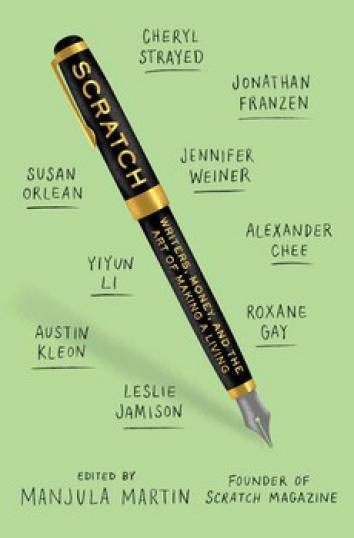

Scratch: Writers, Money, and the Art of Making a Living edited Manjula Martin. Simon & Schuster.