According to cannibalism researcher Bill Schutt, the idea of people eating people is always lurking somewhere in the collective Western id, one of those tops-all taboos that manages to revolt and captivate in equal measure. I’d argue it’s more horrifying a concept than incest, bestiality, ritual dismemberment, and that thing called coprophilia where people are really into poop. Our collective push-pull response to cannibalism explains our fascination with Jeffrey Dahmer, Schutt says, and also why Hannibal Lector is considered one of the greatest screen villains in movie history. We can’t look away, even when we want to.

Now Schutt’s new book, Cannibalism, which explores the practice across the animal kingdom, argues that we can actually learn a lot from observing any species that sometimes eats its own kind—including our own. Cannibalism has much to teach us about evolution, disease, racism, and even familial sacrifice and love. And it also, unsurprisingly, makes for delectable reading.

Schutt, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History, writes that the scientific community’s understanding of cannibalism in the animal kingdom has changed in recent decades. Once thought of as aberrant behavior in response to extreme situations involving starvation or captivity, cannibalism is now understood to be a characteristic that varies from freakish to downright common depending on the species. It serves “a variety of functions,” Schutt writes, and there are even “examples in which an individual being cannibalized receives a benefit.” Spadefoot toad tadpoles eat other tadpoles. Some snail mothers lay two sets of eggs—one intended to hatch and the other intended to be eaten by those who hatch. (Schutt calls these “kids’ meals.”) Cichlid fish that practice mouthbrooding, in which the parents protect their eggs and babies from predators by carrying them around inside their mouths, sometimes get hungry and swallow their own children. Whoops! In what Schutt calls “an extreme act of parental care,” black lace-weaver spider moms call their hungry babies over and allow their children to eat them alive.

Among invertebrates, there are rules of thumb: Females cannibalize more often than males; the old and young are the first to go. And the practice continues further up the food chain, as well, though in mammals it’s less common.

“Cannibalism occurs in every class of vertebrates, from fish to mammals,” Schutt writes. Rabbit, mouse, and hedgehog moms sometimes eat their young when there’s too many in a litter for the food available or when babies are born dead or deformed. Among chimpanzees, our closest relatives, adults of both sexes have been known to kill and eat babies unrelated to them in response to hunger, dwindling resources, and even, perhaps, a desire for sex. (Jane Goodall observed that chimpanzee moms whose babies were killed and eaten by adults from another community were “likely to come into oestrus within a month or so” and would then be available for “recruitment.”)

Schutt’s chapters on cannibalism among humans are the most fascinating, though it’s a tough subject to study systematically. Human don’t exist in the wild; cultural beliefs get in the way of us expressing behavior that might or might not come naturally to us. And it’s hard to know how far back our cultural taboos related to human-eating go; if ancient peoples were devouring one another’s livers with a nice Chianti, they weren’t writing it down. Schutt traces the cannibalism-is-bad concept through Western literature and fairy tales; in the latter, he writes, child-chomping ogres sometimes served as the ultimate morality police—behave or be eaten. He explores cannibalism as an act of last resort in a disturbing chapter about the ill-fated Donner Party, titled “The Worst Party Ever.”

But, as Schutt points out, we are discriminating about what we call cannibalism. Historical claims about savages eating one another are sometimes wildly hyperbolic, or lacking in proof, Schutt finds. Accusations are often undergirded by racism and opportunism. When Spain was exploring and exploiting the Caribbean during the 1500s, a 1510 papal decree that Christians were morally justified in punishing cannibals meant that on “islands where no cannibalism had been reported previously, man-eating was suddenly determined to be a popular practice.” Yet Renaissance-era Europeans who would have been disgusted by reports of people-eating rituals in faraway places nonetheless practiced what Schutt called medicinal cannibalism. “Upper-class types and even members of the British Royalty ‘applied, drank or wore’ concoctions prepared from human body parts,” Schutt writes. And blood was consumed to treat epilepsy:

So popular was this practice that public executions routinely found epileptics standing close by, cup in hand, ready to quaff their share of the red stuff.

Schutt suggests that this cultural myopia is the reason we don’t label as cannibalism, say, the contemporary fringe practice of moms eating their placentas after giving birth. The tissue is “derived from the fetus,” after all. Schutt travels to Texas to take up a home schooling mom of 10 on an offer to eat her placenta. Fried in a sauté pan with garlic and onion, Claire’s placenta looks like liver, chews like veal, and tastes like chicken gizzard.

So what does cannibalism look like in a culture that doesn’t attach as much stigma to it? Like many other peoples, the Chinese practiced survival cannibalism during wars and famines; an imperial edict in 205 B.C. even made it permissible for “starving Chinese” to exchange “one another’s children, so that they could be consumed by non-relatives.” But, according to historical sources cited by Schutt, the Chinese also practiced “learned cannibalism.” In Chinese books written during Europe’s Middle Ages, human flesh was occasionally cited as an exotic delicacy. In times of great hunger or when a relative was sick, children would sometimes cut off their flesh and prepare it in a soup for their elders. One researcher found “766 documented cases of filial piety” spanning more than 2,000 years. “The most commonly consumed body part was the thigh, followed by the upper arm;” the eyeball was banned by edict in 1261.

This is dark stuff to contemplate, which may be why my favorite portion of the book deals with the preposterous and rococo cannibalism that takes place as part of the sexual practices of redback spiders. Schutt’s wry tone is well-suited to this scientific retelling, and I found myself reading portions of the book aloud to my husband (although I might have enjoyed it more because it’s not the female who has her innards chewed out).

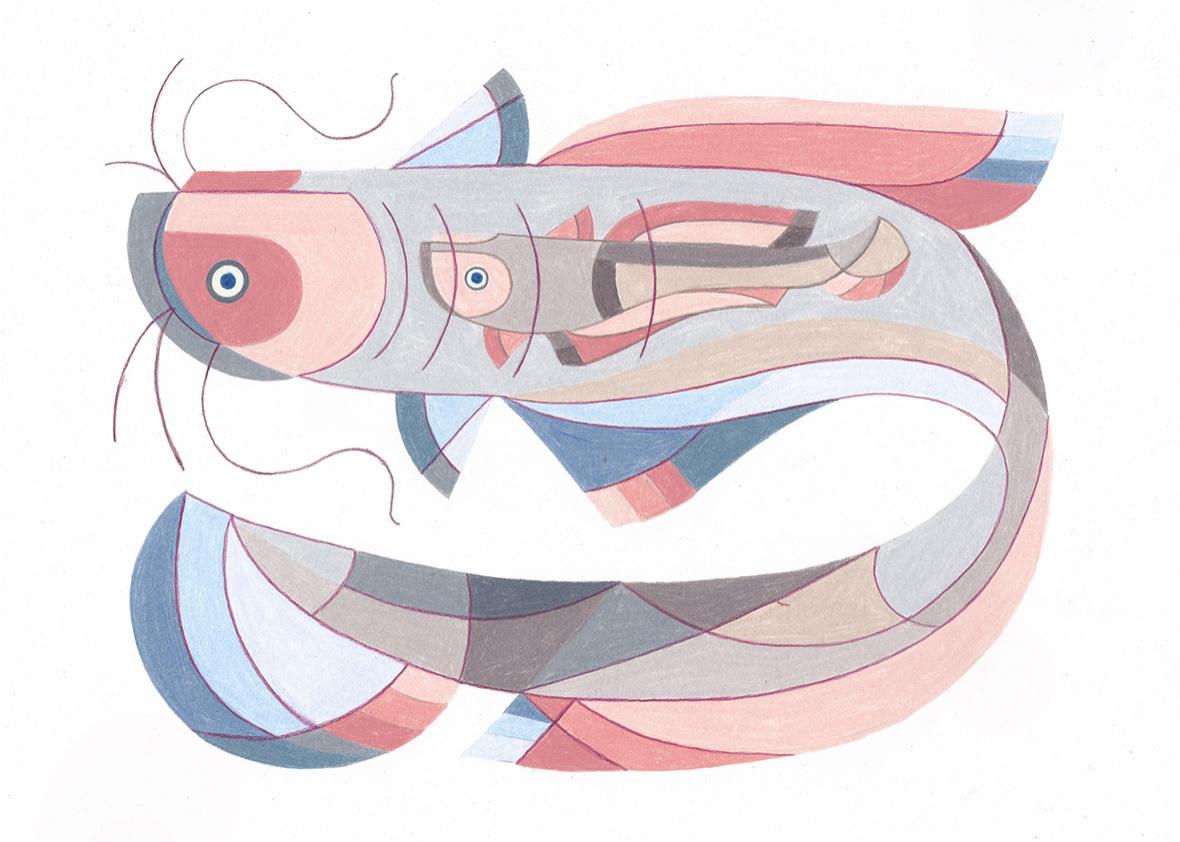

Basically, among redback spiders, the female is five times as large as the male, which contributes to a certain power imbalance. The male approaches, with perhaps not as much trepidation as might be called for, and tries to get the attention of his lady lover by bouncing around and waving his legs. Courtship continues with some “abdominal vibration” and some “epigynal scraping” and something called “Gerhardt’s position 3” (it sounds complicated, but there are step-by-step illustrations if you want to try it), and all of this is followed by the male performing a slow somersault in the middle of copulation. At this point the female vomits on the male and consumes his abdomen as they mate. He walks away, comes back for more (fool!), and as they resume copulation, she resumes eating him—“eventually snorking up his now enzyme-liquefied innards like a spider-flavored Slurpee.”

Why does the male bother? There appears to be an evolutionary advantage. Scientists have found that cannibalized males “copulated longer and fathered more offspring than non-cannibalized males.” So there’s that. Nature wants what it wants.

—

Cannibalism by Bill Schutt. Algonquin.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.