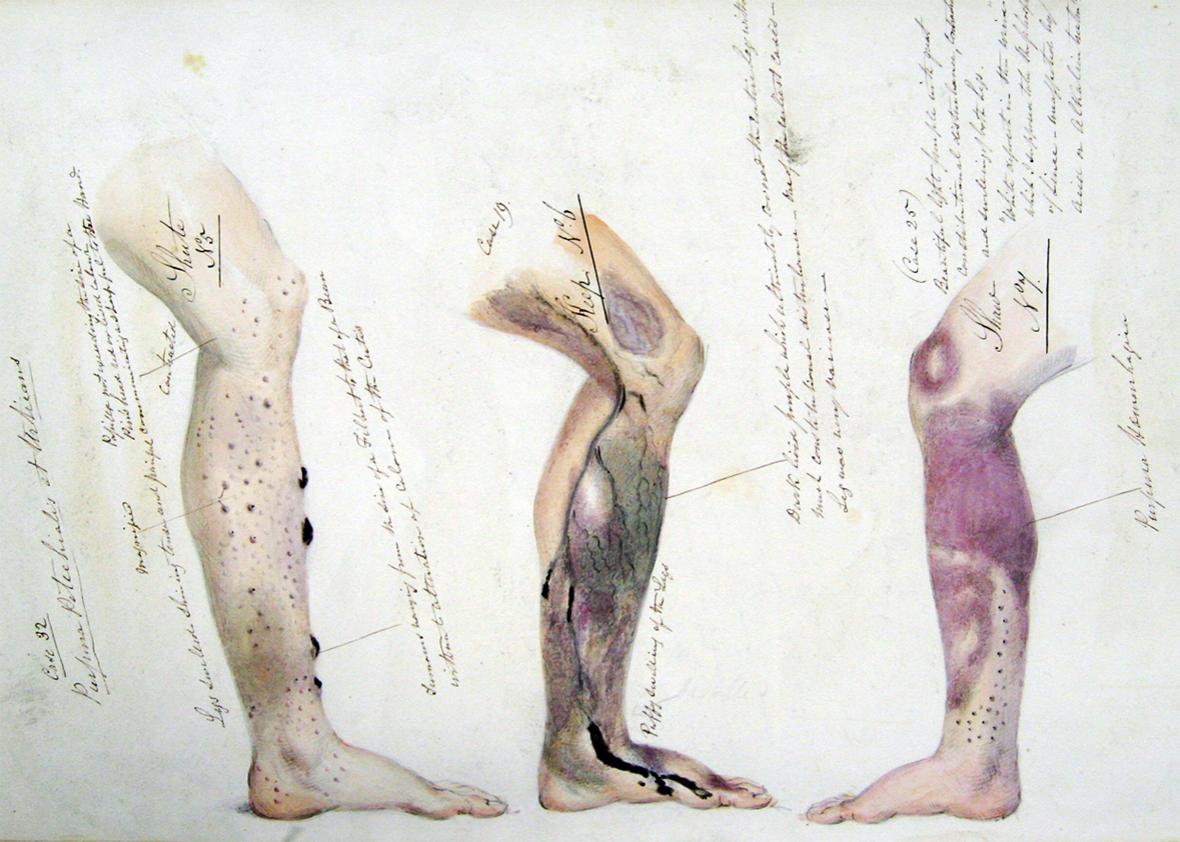

Due to a genetic quirk humans picked up somewhere in our evolution, if you go about three months without the vitamins that fresh food provides, your body loses too much ascorbate (or vitamin C) to carry on. Ascorbate helps the body create collagen, the essential protein in the body’s connective tissue, and a deficiency is deeply painful. Sailors afflicted with scurvy, Jonathan Lamb writes in his engrossing cultural history Scurvy: The Disease of Discovery, “found their limbs growing stiff and their skin bruised and ulcerous. … Their gums grew black with corrupted blood and swelled so much the mortified flesh hid their teeth.”

A patient beset with scurvy is termed “scorbutic.” In the scorbutic body, as connective tissue fails, long-healed broken bones unknit themselves, and legs cramp so severely that the person cannot walk. By one estimate, Lamb reports, this debilitating malady killed 2 million people serving on ships between 1500 and 1800, “ranking as the premier occupational disease of the great maritime era.” All those sailors—and officers—fell through a critical gap between the relative progress of engineering and medicine. They died in agony because Europeans had figured out how to get bodies across oceans, but not how to keep them healthy on the way.

In Lamb’s book, gruesome descriptions of mortified flesh take a back seat to a larger argument about the way the disease colored the experience of exploration during the Age of Sail, shifting social relationships and affecting perceptions. One of scurvy’s characteristics was a type of homesick nostalgia. Another was an extreme lability of the emotions, so that men with scurvy cried often and unpredictably or succumbed to dangerous fits of temper. (Lamb suggests that Herman Melville’s Ahab was “the fictional synthesis of the infatuation of scorbutic commanders. Inexplicable, terrible, and capricious, they exhibited the properties of scurvy itself, lieutenants of a dangerous and unpredictable force menacing the system and even the physical structure of the ship.”) A third emotional symptom of the disease was a fixation on the person’s own pain. As Lamb points out, you might think that the widespread nature of the disease would translate into a sense of solidarity among those with scurvy; instead, scorbutic people tended to withdraw into their own misery.

Scurvy changed the way you saw the world, even when relief was in sight. Afflicted people who made it to landfall (and the opportunity to save themselves through an infusion of fresh food) were simultaneously “dazzled” and horrified by the sights and smells of the landscapes and vegetation. (Sometimes, Lamb reports, they died because they were so overwhelmed by their bodies’ yearnings for the land.) Because the places they landed were also new and exotic to European travelers, the brain’s biological drive for vitamin C augmented and warped their experiences of exploration. This is the crux of Lamb’s argument: that the widespread presence of scurvy inherently altered the way Europeans perceived the new places they “discovered.”

Take Lamb’s many anecdotes about people with scurvy who pathologically fixated on seemingly small details in their surroundings. Lamb quotes a long passage from William Dampier’s observations of the sky on the approach to New Holland (Australia), in which the explorer finds himself fraught by emotional responses to clouds and sun, committing the minute changes in the sky to paper in, Lamb writes, “detail out of all proportion to the significance of what is observed.” At the same time, other scorbutic travelers evinced disgust or fear at the new animals, plants, and landscapes they encountered. After landing in Mauritius in 1768, French botanist Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre wrote that all of the plants he found were horribly unpleasant-smelling and sour-tasting. Here, the scientist’s impulse to record and observe was twisted up by the influence of scurvy on his taste buds.

Lamb’s story of scurvy is also a story of the halting progress of scientific discovery. Before I read this book, my vague understanding of the way scurvy was “solved” went like this: British sailors had trouble with the disease; eventually, ship’s surgeons realized that citrus fruit was the answer, and they began to mandate that ships store limes or lemons along with other provisions. (I must have read this tale in a children’s book at one point, because I retain a very clear mental picture of a cartoon barrel of limes, with merry, healthy sailors dancing around it.)

As Lamb makes clear, the path to understanding and fixing the problem of scurvy was not at all so straightforward or triumphant. Scurvy was often attended by other diseases of malnutrition—pellagra, beriberi—so its unique symptoms weren’t always easy to disambiguate, and some treatments that seemed to alleviate the malady were actually working on those diseases instead. (Woe to those many men who depended on malt wort for their anti-scorbutic.) Surprisingly late in the Age of Discovery, doctors invested in the theory that scurvy derived from a nutritional toxin present in a ship’s provisions overruled those who correctly believed that the disease came from a vitamin deficiency; this stubbornness consigned another generation of seafarers to suffering. Shadowing all of these confusions was the fact that scurvy was freighted with shame. A ship’s officers tried to hide the fact that it had struck their ship, which delayed progress in understanding the disease.

If some stretches of Lamb’s book can be dizzying in their scope, with examples stretching across centuries and oceans deployed to argue larger thematic points, the chapter that’s situated in Australia brings all of these ideas together in most satisfying fashion. Down Under, the land offered little in the way of natural anti-scorbutics, and convicts and colonists suffered greatly from the disease. Its effects, as Lamb neatly shows, exacerbated the sufferings of the convicts, who were provided very little in the way of fresh food; as in his passages about scurvy on board slave ships, I was struck by the realization that scurvy was often one more weapon in the arsenal of the oppressor during an age of colonization. (Lamb’s flash-forward analysis of George Orwell’s 1984 as a scorbutic fiction—remember when Winston goes to jail, starves, and loses his mind?—cements this perspective.)

Two-hundred years ago, Australia’s penal regime caused scurvy in its prisoners, through poor diet, and then condemned them for stealing greens from the colony’s nascent gardens to feed their bodies. In the United States, in 2016, Michigan has still not restored clean water to Flint, after two years; the lead poisoning there may cause all kinds of physical and mental complications for residents. Lamb’s book shows just how hard it can be for humans to fix an endemic problem when pride and prejudice get in the way.

—

Scurvy: The Disease of Discovery by Jonathan Lamb. Princeton University Press.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.