For a collection of essays about contemporary culture, Against Everything, by n+1 magazine co-founder Mark Greif, begins in an unlikely place: walking the perimeter of Walden Pond, accompanied by the spirit of Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau’s curmudgeonly presence floated above Greif’s childhood in the Massachusetts suburbs, not far from the site of the transcendentalist’s one-room cabin. Greif describes venerating the “principle” of Thoreau long before he was old enough to read his writings, visiting the pond with his mother, who made a ritual of musing, “I wonder what he would have thought of that?” “I knew a ‘philosopher,’ ” Greif writes in the preface, “to be a mind that was unafraid to be against everything.”

By evoking Thoreau, Greif aligns himself with one of the more neglected traditions of the essay: the highbrow polemic, a vanishing art in an era in which the personal often eclipses the philosophical. (In the introduction to this year’s Best American Essays, editor Robert Atwan laments that the intellectual salvos of another transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson, have fallen out of favor due to their “chilly impersonality” and exerted “little influence on future essayists.”) Greif sometimes appears as a character in the essays of Against Everything—most of which were previously published in n+1—but he emphasizes that he picks at the seams of his own hypocrisies only to uncover the self-deceptions that also ensnare us, his readers. Instead of revealing an “I,” he attacks a “we.” But there’s an untrammeled optimism in being against everything—which, for Greif, entails being for something better than what already exists. The essays have a habit of changing direction in midair, sticking the landing as earnest entreaties for change. There’s a whiff of 19th-century utopianism floating through this collection, which seems to harbor a belief that the right ideas, well-communicated, could make the world a better place.

The first essay in the collection, “Against Exercise,” from the inaugural 2004 issue of n+1, remains one of Greif’s best, and establishes a paradigm for the rest of the book to follow. It transforms a seemingly straightforward habit—going to the gym and sweating out some calories—into a symptom that reveals a society gone wrong. In an age when physical well-being has become, at least for those who can afford it, easier to maintain than ever before, Greif accuses us of needlessly “disposing of the better portion of our lives in life preservation.” He harangues us to consider what we could be accomplishing with the time we spend lifting weights or logging miles, hoarding healthfulness in tiny increments. “It might have been naïve to think the new human freedom would push us toward a society of public pursuits, like Periclean Athens, or of simple delight in what exists, as in Eden,” he admits—but if so, Greif is not too cool to admit disappointment. At the end of another essay—which levels a similar critique against health-food culture—he asks, “If, in this day and age, we rejected the need to live longer, what would rich Westerners live for instead?”

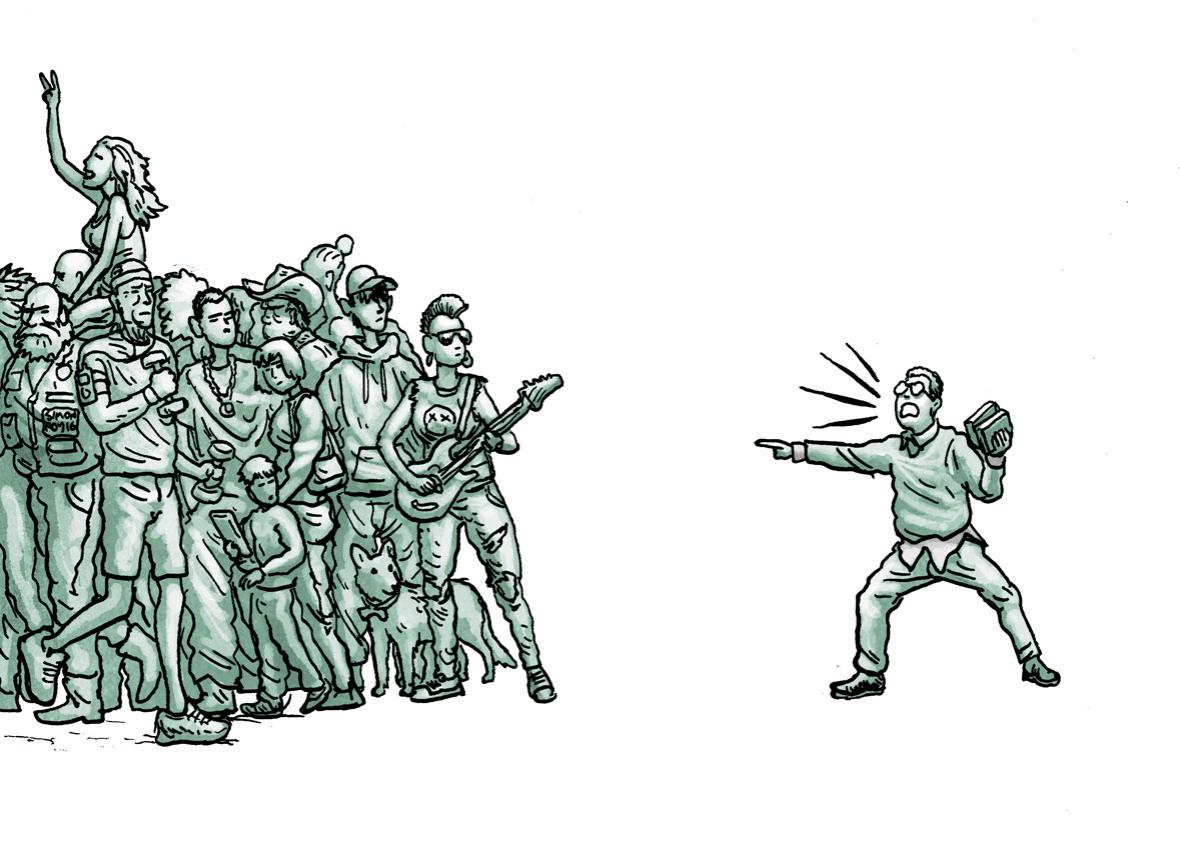

Of course, the promise to find fault with everything is not the most naturally winning premise for a book of essays. This is doubly true when the essays are coming from someone who earnestly name-drops the likes of Pericles, Thoreau, Flaubert, and Epicurus in rapid succession. The book succeeds on the strength of its deadpan and sometimes disarmingly bizarre humor. (“Exerciser, what do you see in the mirrored gym wall?” Greif intones in the first essay. “You make the faces associated with pain, with tears, with orgasm. … You groan as if pressing on your bowels.”) It’s especially important that most of the laughs come at Greif’s expense. “This is not a book of critique of things I don’t do,” he writes in the preface. “It’s a book of critique of things I do.” At the Occupy Wall Street protests in Zuccotti Park, he is the “little bourgeois” who cringes to think how this ragtag democracy appears “from boardroom windows high above.” In the book’s most personal entry, previously published only in German, Greif seeks to remedy his failure to appreciate the cultural importance of hip-hop by trying, in his mid-30s, to teach himself to rap. “It’s a fortunate fate to have your lifetime be contemporary with the creation of a major art form,” he writes. “Embarrassing, then, not to have understood it, or appreciated it, or become an enthusiast, even a fanatic, from the first.” More compromising than this revelation, however, is the figure Greif cuts practicing his bars on the subway. He has judged us, but he has also prostrated himself for our review.

The essays come off not as posturing, but as the exertions of a formidable mind using every tool at its disposal for what Greif considers an all-important task. The book is organized loosely by theme—body, music, visual culture, and so on—with a series of musings titled “The Meaning of Life,” Parts I–IV, interspersed between the sections as a kind of philosophical backbone. In the first of these pieces, Greif looks to Gustave Flaubert’s personal credo of “aestheticism,” in which every part of life is treated as a work of art, and Thoreau’s “perfectionism,” in which the improvement of the self becomes the purpose of existence, in search of methods for achieving happiness. Greif calls the modern self-help genre a “debased” form of perfectionism. But his book also aspires to provide a kind of self-help, just of a higher order.

No matter how broad a “you” or “we” Greif addresses, his essays stem, of course, from one person’s particular interests and experience. When Greif pillories, say, New York hipsters, his points feel acutely and attentively observed. Occasionally, however, a narrowness of perspective undermines the book’s sweeping second-person. Its least convincing installment applies the framework of Marxist critique—a familiar approach for n+1—to the contents of YouTube, alleging but not explaining how the disappearance of videos for copyright infringement reveals “what They think of us, and how we should feel about Them.” Another essay, about the role of police in democracy, feels more relevant to the era of Occupy Wall Street protests than to the current moment of Black Lives Matter, though it was published in 2015.

The word we is, in some ways, the riskiest pronoun for a writer to use: It raises the question of who is included, introducing a binary that invites the reader to either opt in or opt out. It’s a mark of the thrilling force of Greif’s reasoning, and of his writing’s palpable sincerity, that I, for one, felt justly implicated, absorbed from the start into the receiving end of his rebuke. Then again, I fit squarely into the class of people Greif clearly envisions as his audience, a category that seems broader in some essays and narrower in others; in his prologue, Greif aims the book at “the middle classes, or people in the rich nations, or Americans and Europeans and their peers the world over.” One of Greif’s early pieces, “Radiohead, or the Philosophy of Pop,” explains why the word we is “the most important grammatical tic” in the band’s lyrics—and perhaps also suggests why it crops up so often in these essays. Invoking a “we,” Greif writes, represents an “imagined collectivity” that “may shade into the thought of all the other listeners besides you, in their rooms or cars alone, singing these same bits of lyrics.”

Greif writes to dress down his imagined collectivity, but also, it seems, to summon us up, into existence. “[Y]ou cannot strike the colossus,” he says in “The Philosophy of Pop.” “But you can defy it with words or signs.” An essay can’t overthrow the status quo anymore than a pop song can raise an army—but the best ones are propelled by their ambition to try.

—

Against Everything by Mark Greif. Pantheon.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.