As recently as six years ago, when the Library of America released a collection of Shirley Jackson’s writings, her legacy was uncertain. “Shirley Jackson?” Newsweek critic Malcolm Jones wrote. “A writer mostly famous for one short story, ‘The Lottery.’ Is LOA about to jump the shark?” True, no one who’s read “The Lottery” is ever going to forget it. The story created such a sensation when it appeared in the New Yorker in 1948 that the magazine issued a press release saying it had received more mail in response to it than to any work of fiction it had ever published. But Jackson also wrote many other indelible short stories, as well as two great short novels, one of which, The Haunting of Hill House, was nominated for a National Book Award in 1960.

Hill House lost to Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus, a fact that pretty much encapsulates Jackson’s professional plight. She wrote spare, idiosyncratic, unsettling fiction, tinged with a hectic misanthropy, about misfits, oddballs, and the chronically overlooked. Her main characters were almost always women, many of them on the threshold of coming unhinged. Her literary mode was the gothic and her great theme was the terror and allure of domesticity. As darkly uncommercial as this might sound, her books—particularly her last completed novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle—got good reviews and even became best-sellers. But no one thought of them as “great,” because she published during an era when American culture could only conceive of a particular kind of novel, the kind that Roth (and Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer and John Updike) wrote, as “great.” When women appeared in those novels, it was mostly to be resented for their refusal to fulfill the role of uncomplicated suppliers of nurturance and sex.

But Jackson, unlike so many once-popular novelists, did not subside into obscurity. A small, steady following for her work persisted over the next five decades, keeping her books in print and awaiting favorable conditions for a revival. A new biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by the critic Ruth Franklin, represents the latest and most concerted attempt to reclaim the writer’s reputation. It’s also a fresh effort to frame her as an artist with extraordinary insight into the lives, the concerns, and—above all—the fears of women. Franklin doesn’t attempt to portray Jackson as a feminist. The F-word seldom appears in Shirley Jackson, although Franklin makes frequent reference to Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, a book that does capture some of the confusion and dissatisfaction of Jackson’s life and work. The iconography of 20th-century literary feminism rests uneasily on Jackson’s shoulders. She was tragic, but obscurely so. Unlike Sylvia Plath, she wasn’t tormented to her doom (or not exactly) by a dastardly husband, and unlike both Plath and Joan Didion, Jackson—plain, overweight, wearing a shapeless housedress when she even went out at all—made a cosmetically unappealing role model for the sort of young literary women who, being young, care about appearances more than they like to let on.

Besides, no one could ever quite get a bead on Shirley Jackson. She was, as Franklin writes, “an important writer who happened to be—and to embrace being—a housewife, as women of her generation were all but required to do.” (Jackson was born in 1916.) She wrote disturbing fiction that gave some of her readers nightmares, and she also wrote hugely popular humorous essays about raising the four children she had with her husband, the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman. (Franklin writes that Jackson “essentially invented the form that has become the modern-day ‘mommy blog.’ ”) Far from discouraging her, Hyman considered Jackson a genius and berated her for not spending more of her time writing—although granted, this was partly because they always needed the money. For much of their marriage, she outearned him.

Jackson’s contemporaries found the contrast between her fiction and nonfiction—the eerie and the cheery—baffling. Just as perplexing to the present-day devotee of her stories and novels is the marked contrast between Jackson’s life at the center of a boisterous bohemian family and the fragile, isolated characters she invented. The daughter of a highly conventional California socialite who never ceased to voice her disappointment in her daughter, Jackson rebelled comprehensively: by marrying a Jew, by taking few pains with her grooming, by keeping a messy house, by telling the world all about it. Yet she was never able to shake her mother’s influence, dutifully writing to her parents and submitting her life for their disapproval throughout her entire adulthood. One of the most poignant documents in Franklin’s book is a letter Jackson wrote to her mother after she received glowing coverage for We Have Always Lived in the Castle in Time, only to have her mother focus entirely on the unflattering photograph the magazine used. “Surely at my age,” Jackson retorted, “I have a right to live as I please, and I have just had enough of the unending comments on my appearance and faults.” She never mustered the nerve to send it.

Jackson met Hyman when they were both students at Syracuse University; he announced he would marry her, sight unseen, after reading a story she published in a campus journal. The young couple scraped by in Greenwich Village for a few years, then Hyman got a job as a staff writer for the New Yorker. He remained on a retainer at the magazine for the rest of his life, but in the 1950s the family moved to Vermont, where Hyman joined the faculty of the progressive women’s college Bennington College. A charismatic talker and dedicated mentor, Hyman taught what was for many years the university’s most popular course “Myth, Ritual, and Literature.” He was Jackson’s first reader (the pair edited each other’s work) and a top-notch literary champion. One of the couple’s closest friends, the novelist Ralph Ellison, wrote much of his own masterpiece, Invisible Man, in the Hymans’ rambling old Vermont house, Hyman’s relentless encouragement spurring the often-blocked Ellison on. Jackson was a gifted, adventurous cook. They threw famous parties, whose guests included such luminaries as Dylan Thomas, the poet Howard Nemerov, and Bernard Malamud.

But Hyman was also chronically unfaithful to Jackson, flatly refusing to make even a pretense of monogamy, no matter how much misery this caused his wife. And his criticism often tormented Jackson, much as her mother’s did, a bitter irony when she’d picked him, in part, for the ways he seemed her parents’ opposite. When, in the years leading up to her sudden death by heart attack in 1965, Jackson seriously contemplated leaving her marriage, she accused Hyman of subjecting her to “mockery.” Franklin does not establish the themes of his criticism, beyond her haphazard writing regimen and the disorder of her work area, but this was apparently a big problem. One of Franklin’s discoveries is the correspondence with a fan, a fellow housewife in Baltimore, that Jackson kept up in the early 1960s (while she was writing We Have Always Lived in the Castle). A cache of Jackson’s letters turned up in the woman’s attic after her death in 2013. In one, Jackson reported that Hyman refused even to enter her office because her bookshelves weren’t alphabetized.

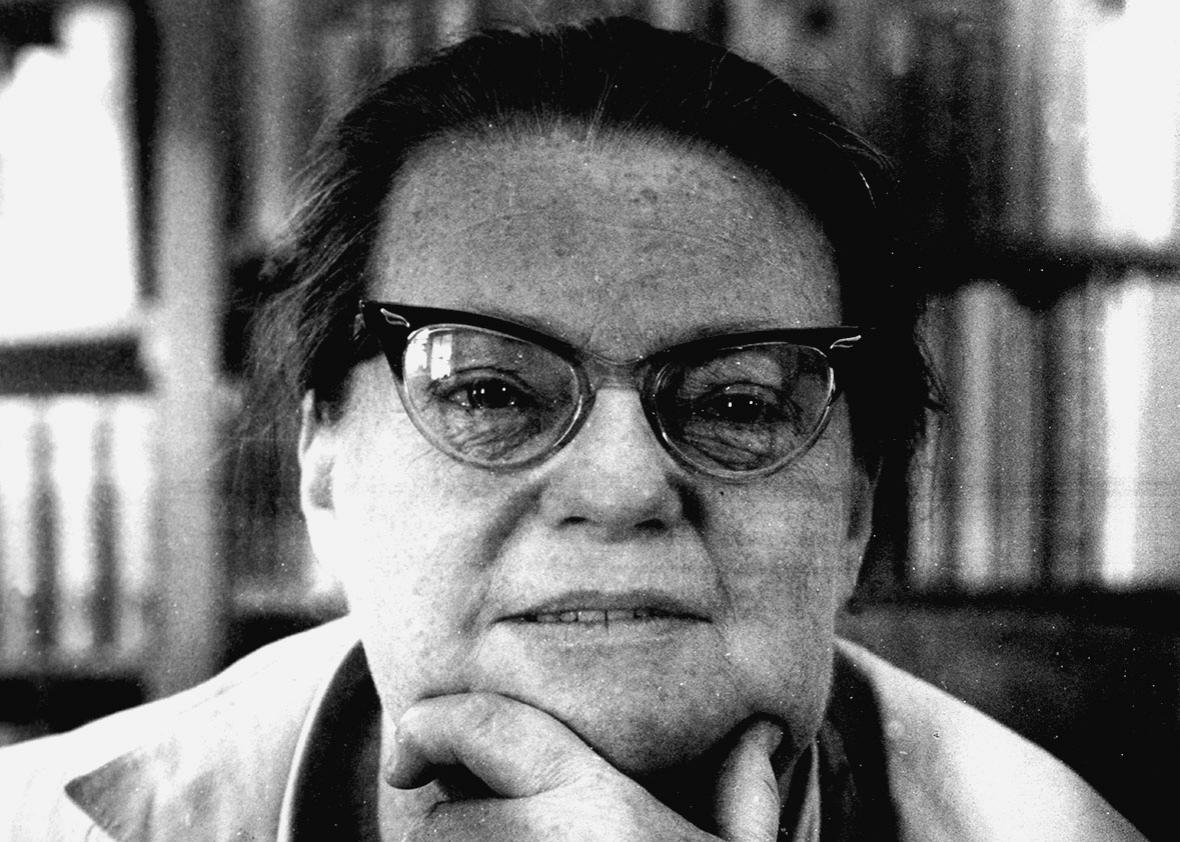

Alan Chin

The novel Jackson was working on when she died, Come Along With Me, is narrated by a middle-age woman whose husband has just died under unclear circumstances. She sells everything they owned and moves to another city under a new name, Angela Motorman. (Jackson, Franklin observes, considered driving the epitome of freedom.) She hangs out a shingle as medium, which provides that whiff of the occult that had long been associated with Jackson’s fiction—but her jaunty, enterprising self-confidence sets her apart from all of Jackson’s other heroines. Franklin believes that Jackson, at the peak of her powers, was about to embark on a new phase of her career and perhaps her life. In her final diary, she wrote of her longing “to be separate, to be alone, to stand and walk alone, not to be different and weak and helpless and degraded … and shut out. Not shut out, shutting out.”

This does sound very much like the cry of a later generation of feminists, women who left stifling conventional marriages to find themselves. Franklin writes that Jackson’s “preoccupation with the roles that women play at home and the forces that conspire to keep them there was entirely of a piece with her cultural moment, the decade of the 1950s, when the simmering brew of women’s dissatisfaction finally came close to boiling over, triggering the second wave to the feminist movement.” But Jackson both does and doesn’t fit this mold. Far from interfering with her creative work, her family actually depended on it. And Jackson genuinely enjoyed running a household and raising her children. It’s conceivable that, if she had lived to see the rise of second-wave feminism, she would have found it uncongenial or irrelevant.

And yet, Jackson’s unhappiness was tied to her gender. Hers are novels of identity, like Invisible Man, a work that shares many of the same undercurrents. Both Jackson and Ellison wrote about wrestling with roles imposed not just by a white male-dominated society, but also by people who share one’s assigned identity. In Jackson’s stories and novels, other women are always the strictest enforcers of correct feminine behavior, a phenomenon she experienced firsthand from childhood. In an early draft of The Haunting of Hill House, quoted in Shirley Jackson, a character remarks, when her sister urges her to get married, “Perhaps she found the married state so excruciatingly disagreeable herself that it was the only thing bad enough she could think of to do to me.” To belong requires miserable compliance; if you refuse, you will be “shut out,” and miserable in a different way.

The tension infusing this unbearable choice fills Jackson’s fiction with doubles and imposters, selves distributed among multiple characters, and in the novel The Bird’s Nest, a heroine with multiple personalities. The uncanniness in her novels and stories derives from a sensation that people who feel unfree to be themselves are haunted by the selves that cannot be. (Henry James, a profound influence on Jackson’s scenarios, although certainly not on her prose, once wrote a story in which the narrator is pursued by the ghost of the man he would have been had he lived his life differently.) The vertiginous, diffuse terror Jackson so excelled at inspiring comes from the sense that her characters don’t even really know who they are. This is distinct from Franklin’s understanding of the occult in Jackson’s work as “a metaphor of female power and men’s fear of it,” which implies that the fear is merely external. You don’t have to be a woman to be subjected to the psychic pressure that leads to such fracturing, but if you are a woman (or, in Ellison’s case, black, or James’ case a deeply closeted homosexual), you are far more likely to be.

It wasn’t feminist critics who kept the flame of Jackson’s reputation lit over the past half-century, but genre writers. Since 2007, the Shirley Jackson Awards have recognized “the legacy of Shirley Jackson’s writing,” by singling out works of “outstanding achievement in the literature of psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic.” Stephen King, in the 1981 collection Danse Macabre, pronounced Hill House on par with James’ The Turn of the Screw. But this association with horror led many critics, in Jackson’s day and since, to treat her work, patronizingly, as a vehicle for chills. (One critic made Hyman apoplectic by describing Jackson as “a kind of Virginia Werewoolf among the séance-fiction writers,” as if anyone who could produce a line like that were in a position to rule on another writer’s “seriousness.”) Just as there is no reason why a novel by a woman should be any less significant than a novel by a man, there is no reason why a story with a ghost in it should be automatically deemed more frivolous than a coming-of-age yarn. (Otherwise, Hamlet is in trouble.) Gender is not the only prejudice that has kept us from acknowledging the brilliance of Shirley Jackson, but Franklin’s biography is a giant step toward the truth.

—

Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin. Liveright.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.