The novelist Colson Whitehead has always been preoccupied with work—its capacity for both excruciating drudgery and the realization of inner truths. His characters have often sought its deeper currents, beginning with Lila Mae Watson, the mystically inclined elevator inspector who was the heroine of 1999’s The Intuitionist, and ranging through the card players Whitehead rubbed shoulders with in his 2014 memoir of a foray into the world of professional poker. Race is another persistent theme in his books, although as far back as The Intuitionist, this constitutionally diffident writer was mocking his own propensity for choosing “my stock ironic black man character” as protagonist. His approach to race, while sustained, has always been oblique. You could count on him to tell you things you didn’t already know in a style you hadn’t already heard.

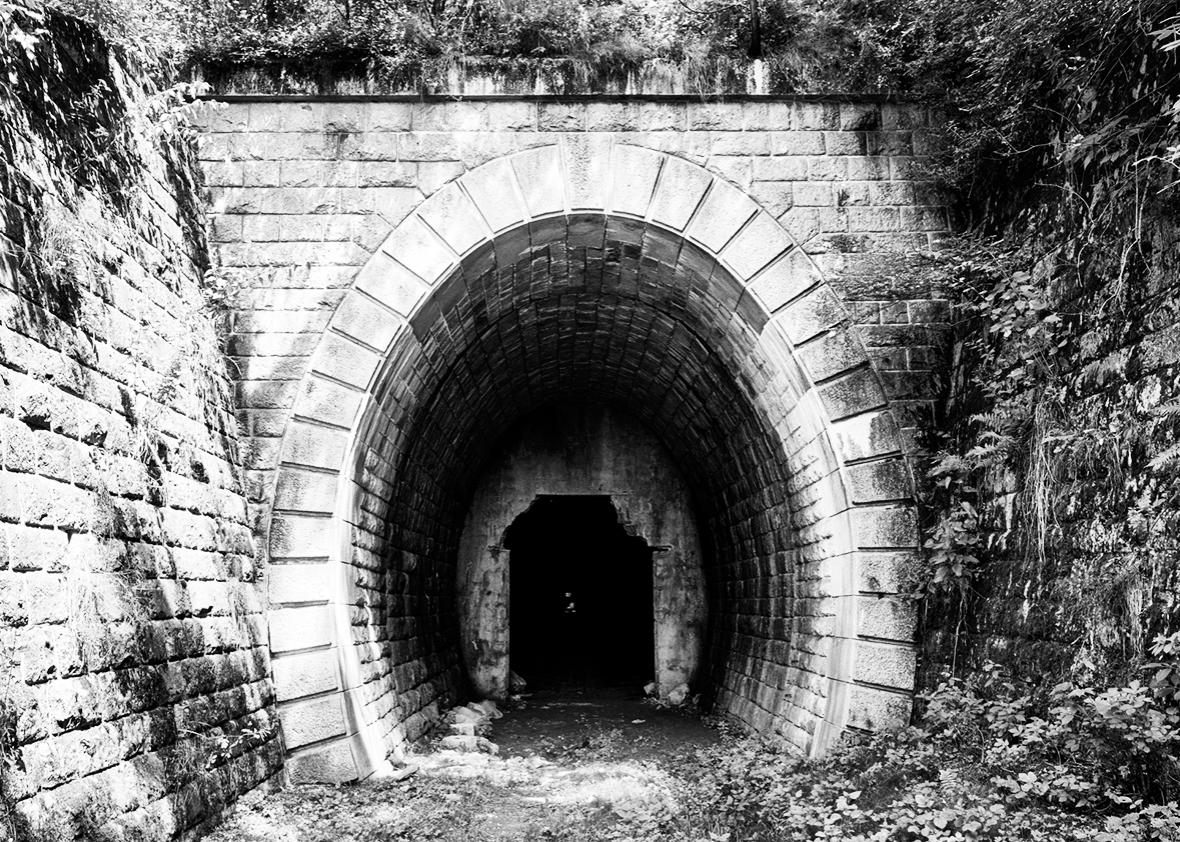

So perhaps it was inevitable that Whitehead would one day write about slavery in America, as he does in his new and already much-celebrated The Underground Railroad. Slavery is the rape of work, the perversion of labor from a potential source of pride and self-discovery into an endless torment. Cora, the heroine of Whitehead’s novel, flees a cotton plantation in Georgia at the age of “sixteen or seventeen”—even the basic self-knowledge of her own birthdate has been denied her—when conditions promise to go from routine brutality to baroque sadism with the arrival of a new owner. She takes several trips via the Underground Railroad, which Whitehead reconceives as a literal subterranean track with hidden stations and steam engines running along it. This Underground Railroad is part New York subway (in one scene, Cora stands forlornly on the platform as the train hurtles past her without stopping) and part nightmare theme-park conveyance, each stop providing another tableau illustrating the barbarity of white supremacy. Like the railroad itself, these exhibits have their fantastical elements, but for anyone who knows her history, there’s an alarmingly blurry line between Whitehead’s imaginings and the truth.

But slavery also presents Whitehead with a particular challenge, because as much as he might disparage that ironic black male character of his as “stock,” the irony in his fiction and his fondness for speculative touches have marked a kind of liberation. Nearly 20 years ago, both of these aspects of his work represented a departure from what black American novelists were supposed to produce. “There was the protest novel, and then there was ‘tell the untold story, find our unerased history,’ ” he said in the same 1999 interview. “Then there’s the militant novel of insurrection from the ’60s.” All those forms demanded strict realism, and few black novelists besides Ralph Ellison could thrive without embracing somber earnestness. “I think there are a lot more of us writing,” Whitehead said in 1999, “and [there are] a lot more different areas we’re exploring. It’s not as polemicized. I’m dealing with serious race issues, but I’m not handling them in a way that people expect.”

There is, however, only one acceptable way for a writer to “handle” slavery, a situation that doesn’t accommodate the sly wit that gives Whitehead’s writing so much of its charm. At moments in The Underground Railroad, the novel feels a bit hemmed in by its obligation to present a historically accurate atrocity exhibition and explain its precise significance. While hardly anyone was paying attention, the oft-decried Age of Irony seems to have ebbed and been replaced by a punctilious, emphatic sobriety. Irony doesn’t fit anymore. It requires a shared, darkly amused understanding of both what we pretend to be and what we really are, and the internet constantly reminds us just how many people don’t share such an understanding of our own folly. You have to spell out the true nature of American race relations in the most exacting way, over and over again, because so many Americans cling to a willful denial of that truth.

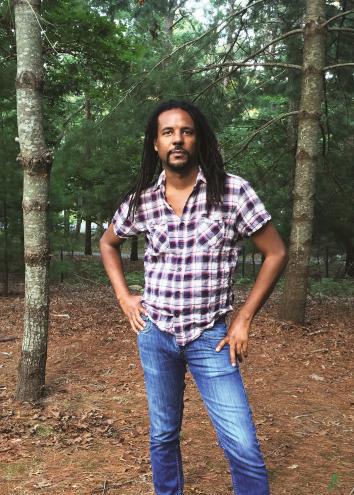

Madeline Whitehead

Any writer who takes up this task risks coming across as a bit of a schoolmarm, and Cora does in fact become just that in one of her post-escape incarnations. Watching some musicians play in a South Carolina town where she first finds refuge, she recalls the enslaved musicians back at the plantation and imagines that this band relishes the opportunity to “attack the melody without the burden of providing one of the sole comforts of their slave village. To practice their art with liberty and joy.” This is pretty on the nose for Whitehead, and it’s no surprise that The Underground Railroad is the only one of his novels that could by any stretch of the imagination become just what it has: an Oprah’s Book Club pick.

Such dissonance between subject and sensibility means this novel ought not to succeed, yet it does. Whitehead finds his commonality with the fierce but rather prim Cora through her stalwart longing to do an honest day’s work for people who will honestly appreciate it. In South Carolina, living in some kind of engineered community, she happily cares for a family with two spoiled children and a neurasthenic but kind mother. The pleasure she takes in decent meals, in owning a soft blue cotton dress purchased with her own money, and in living in a dormitory overseen by a proctor she admires for “the way her clothes were always so crisp and fit just so” is heartrending in its modesty. But then she gets reassigned to perform in a museum exhibit that’s straight out of a George Saunders story, and suspicion dawns that South Carolina is not what it seems. The Underground Railroad is by no means a satire, but sometimes it dances close to the line.

Each stop on Cora’s journey represents a different facet of America’s toxic racial history; Whitehead’s version of North Carolina, for example, chooses simply to purge the whole of its black population, and Cora ends up concealed in an attic like Anne Frank. Pursuing her through this morally blasted landscape is a slave catcher named Ridgeway, the rebellious son of a blacksmith who twists his father’s faith in the virtues of vocation into a savage parody of meaning: “When his father finished his workday, the fruit of his labor lay before him: a musket, a rake, a wagon spring. Ridgeway faced the man or woman he had captured. One made tools, the other retrieved them.” Ridgeway belongs to a long line of obsessive literary bloodhounds, from Victor Hugo’s Javert to Dostoyevsky’s Porfiry—more device than human being but a satisfyingly hateable villain for that. Cora, however, is absolutely believable in every detail as a woman craving order in a demented universe; lying low in a bachelor friend’s house, “after pacing, unable to sit, Cora did the only thing that calmed her. She had cleaned all the dishware when Sam returned home.”

The Underground Railroad makes it clear that Whitehead’s omnivorous cultural appetite has devoured narratives of every variety and made them his own. This novel, like much of his work, has the flavor of Ellison’s skepticism—but it’s also redolent of the propulsive, quasi-allegorical quest plot of Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series. Think of The Underground Railroad as the novel where the spirits of two great American storytellers meet in a third. What makes Cora’s mission existential rather than epic is that she just wants to be a human being in a nation hellbent on denying her that status.

For all the fearsome moral stakes at play in the world he’s written, Whitehead never lets his signature sardonicism drift too far out of reach. The station agent for Cora’s first trip on the railroad offers her a hoary bit of advice, right out of an Amtrak brochure: “If you want to see what this nation is all about, I always say, you have to ride the rails. Look outside as you speed through, and you’ll find the true face of America.” But the railroad is, of course, underground; the only thing she can see out the windows is blackness.

—

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. Doubleday.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.