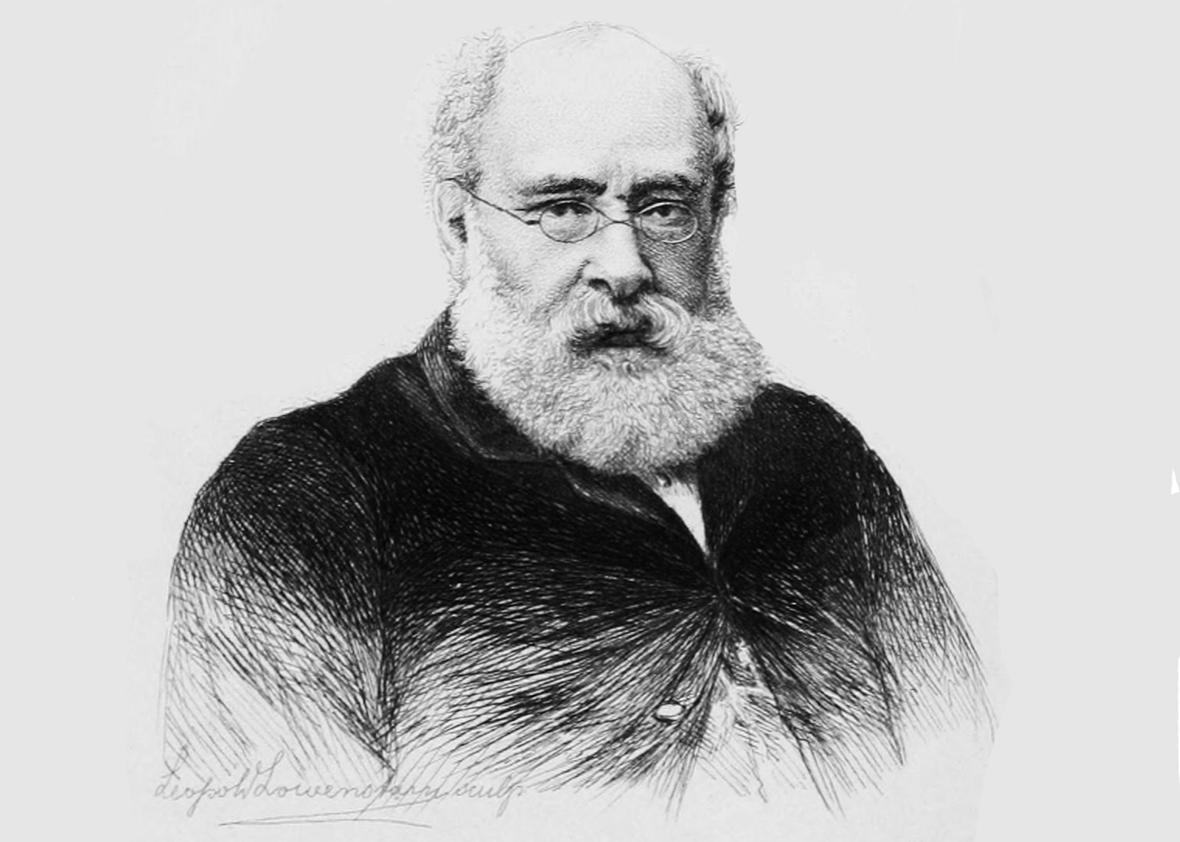

Anthony Trollope’s “great, inestimable merit,” Henry James once wrote, “was a complete appreciation of the usual.” He was right: You won’t find a single uncanny moment in that Victorian author’s 47 novels. Yet reading Trollope in the 21st century can nevertheless be a bit spooky. That’s because seemingly everything that happens today has already been covered in one of his books, albeit in a less technologized form.

An example: Recently, in advance of watching a new adaptation of Trollope’s 1858 novel, Doctor Thorne, I revisited the book. Within a few chapters I came upon an account of a local parliamentary election in the fictional county of Barsetshire, where Trollope’s greatest novels are set. One of the candidates, Sir Roger Scatcherd, is a stonemason turned developer whose fortune has won him a baronetcy despite his coarse, boastful manner and well-earned reputation for drunkenness. During the campaign, someone paints a caricature of him on “sundry walls” about the town of Greshamsbury, pictures in which a laborer “with a pimply, bloated face, was to be seen standing on a railway bank, leaning on a spade holding a bottle in one hand, while he invited a comrade to drink. ‘Come, Jack, shall us have a drop of some’at short?’ ” The working-class voters of the district, “somewhat given to have an opinion of their own,” relish Sir Roger’s rough, plainspoken ways. Still, he has his detractors: As the baronet stands up to make a speech, someone throws a dead cat at him.

I could go on, but the resemblance between particular current events and Trollope’s fiction is like the weather: However much it changes from day to day, in one form or another, it’s always there. His novels amount to a compendium of every recurring pattern of human behavior as observed by a wise, amused, and tenderly exacting deity. He sees all our little self-delusions and vanities, but he loves us just the same. In fact, sometime they make him love us more.

Perhaps it’s the difficulty of filming from such a perspective that makes top-notch movie and TV adaptations of Trollope’s work hard to come by. The new Amazon Prime miniseries based on Doctor Thorne, adapted and hosted by the oleaginous Julian Fellowes, is one of the worst. As Slate’s Willa Paskin has noted, Fellowes, the creator of Downton Abbey, professes to love Trollope and to value the “moral complexity” of his characters, then proceeds to strip all such complexity out of their portrayal. Fellowes’ characters are forever yammering on about how “things are changing” in the class system they inhabit, but the shows themselves cling fetishistically to the past they pretend to critique, sighing over the chandeliers and ogling the ormolu.

Amazon

This was all very well when, with Gosford Park and Downton Abbey, Fellowes stuck to his own material, but Trollope adaptations are so rare that for him to coat one of the divine Barsetshire novels in his distinctive brand of syrup seems especially unjust. Apart from some well-acted but languidly paced BBC adaptations from the 1970s, in recent years there have been respectable adaptations of The Way We Live Now and He Knew He Was Right, but these are two of Trollope’s more sour works. The Way We Live Now, in both its example and in the ambition suggested by its title, seems to have partially inspired the fat “social novels” of the 1990s, and it got mentioned a lot for its depiction of a Bernie Madoff–style financial scheme when that scandal was in the news. But, as Adam Gopnik noted last year in the New Yorker, The Way We Live Now is not typical: Rather, it’s “the Trollope novel for people who don’t like Trollope novels.”

There have been a lot of them. Trollope was popular in his lifetime, but for much of the 20th century, his fiction suffered critical and scholarly disdain. To the modernists intent on shaking off the conventions of Victorianism, he represented the epitome of that era, his serenely omniscient and ironic third-person narrator the essence of bogus authority. An autobiography published shortly after his death in 1882 revealed that Trollope thought of novel writing as more craft than art, and in James’ words, he “never troubled his head nor clogged his pen with theories about the nature of his business.” He is most famous among writers today for the regimen he described in that book: Rising before dawn and working for three full hours every day, even if that meant finishing one novel and starting the next because the allotted time hadn’t expired. Trollope had a day job with the postal service to get to, after all.

That prosaic approach didn’t jibe with the literary world’s efforts to transform the image of the novel in the 20th century. What had once been seen as a lucrative form of entertainment, produced for mostly middle-class and mostly female readers was recast as the highest pinnacle of the literary arts, the work of inspired geniuses answering the call of the muse rather than the landlord. So in the mid-20th century, the imperious critic F.R. Leavis, a loyal soldier in this project of solemnification, pronounced Trollope’s works as “beneath the realm of significant creative achievement” in terms of “the human awareness they promote, awareness of the possibilities of life.” (It’s no coincidence that the promulgation of this heroic notion of the novelist coincided with the rise of the idea that the greatest of novelists must be men, and even a male novelist like Trollope, with, as James put it, a “feminine” interest in the familiar and ordinary, was dismissed.) By the latter half of the century you could get through an entire undergraduate English program with a heavy emphasis on British literature, as I did, and never once be assigned a Trollope novel.

But a funny thing happened to Trollope on his way to the dustbin of history: His novels acquired an avid, amateur readership. It’s impossible to measure such things, of course, but he seems rivaled only by Jane Austen and Arthur Conan Doyle among 19th-century authors with an active contemporary fan base. The Trollope Society of the U.K. maintains an extensive database of books, quotes, and characters—very useful given that quite a few characters appear in more than one novel. The U.S. branch of the society has paid membership, annual meetings, lectures, and regional reading groups.

The reasons for this have little to do the perfection of Trollope’s form or the vividness of his prose. Although he is Austen’s most direct literary descendent, he lacks her discipline, and his novels are notorious for their digressions on fox hunting and Tudor architecture. But his people! Trollope’s great strength lies in his immensely fertile gift for character. He created dozens of indelible fictional people, and among Trollopians you need only mention Mrs. Proudie or Glencora Palliser to elicit laughter or sighs. Even his relatively minor characters are sharply drawn and, unlike Dickens’, rarely caricatured. This is why Fellowes’ broad, sentimentalized adaptation, populated by people who seem lifted from a low-end high-school drama and jammed into corsets and top hats, is such a travesty.

Doctor Thorne concerns three families living in the village of Gresham: the local squire with his wife and four children; Sir Roger Scatcherd, to whom the spendthrift squire is perilously in debt; and Doctor Thorne and his niece Mary. The squire’s only son, Frank, falls in love with Mary, but since he needs to marry a rich woman to preserve his family’s position, his relations pressure him to renounce her. Doctor Thorne knows what nobody else does: that Mary, while illegitimate, stands likely to inherit Sir Roger’s fortune. Still, he finds it prudent, for complex reasons, to keep this a secret throughout most of the novel. This is less a plot than a situation. Trollope likes to set up characters with opposing interests, bring them together and see what happens. The comedy in this comes not from seeing the baddies act nasty and then get their comeuppance. It comes from the reader’s foreknowledge of how poorly each side understands the other, and how often people blunder by mistakenly assuming that others see things as they do.

Trollope’s subject, as ever, is the conflict between true feeling and the Byzantine imperatives of status. His genius lies in his refusal to allow that any individual is entirely free of either. Doctor Thorne, for example, is a man of exquisite scruples and complete sincerity; both get him into trouble despite his essential goodness. Although his profession puts him lower in the class structure than the Greshams, he cherishes the knowledge that his family is even “older” than theirs: “He had a pride in being a poor man of a high family; he had a pride in repudiating the very family of which he was proud; and he had a special pride in keeping his pride silently to himself.” These attitudes are both absurd and understandable; we recognize that they result from the muddling interaction of decency with the imperatives of the real world. They will get the doctor into trouble, but we wouldn’t dream of blaming him for them.

Doctor Thorne’s foil—the squire’s wife, Lady Arabella Gresham—comes from an aristocratic family, the de Courcys, who recur throughout Trollope’s novels as exemplars of haughtiness and a hypocritical preoccupation with “blood.” Lady Arabella finds the Doctor uppity. (Trollope isn’t against status—he knows humanity too well to advocate abandoning it entirely—but his fiction argues for better, more moral ways of allocating prestige.) Among the first things we learn about Lady Arabella is that she has lost four infant daughters to illness and that this tragedy haunts her. She discharges a snooty physician from a neighboring town and retains Doctor Thorne because she believes him to be the superior healer. “The mother’s heart then got the better of the woman’s pride,” Trollope writes.

This is an important precedent because much of what Lady Arabella does to offend Doctor Thorne comes from both aspects of her personality. She doesn’t dislike Mary because Mary is lowborn and poor. She dislikes Mary because she sees her as a real threat to her own son. She can’t imagine that Frank could be happy in a life that would make her miserable, and Trollope is not entirely sure she’s incorrect about that. Her folly, like the follies of all of Trollope’s characters, Doctor Thorne included, is recognizable and understandable no matter how much society changes. The wonder of Trollope’s “usual” is that it has turned out to be eternal.

Fellowes omits all of this, making Lady Arabella into a two-dimensional snob. (She is a snob, but in Trollope’s novel, she’s a three-dimensional one.) That’s just one of the thousand sins Fellowes’ miniseries commits against the original, such as turning the eccentric aging heiress Martha Dunstable (a favorite among Trollopians) into a smirking wisecracker played by the American actress Alison Brie. The last half hour of the adaptation becomes almost unbearable to watch when the memory of the novel is fresh in your mind. But why subject yourself to it? You don’t even need an Amazon Prime account to access the riches of Trollope’s fiction, and there’s precious little time for such unpleasantness when you’ve got 47 novels to read.